Once the [micro-] films are made, there is seldom any need for the scholar to go back to the books and documents themselves.

Richard D. Altick, The Scholar Adventurers, 1950, chap. VII

The Major had told him one day that in five years’ time no one would read any more. Later, archaeologists would ponder on, argue about, what books had been for. ‘It’ll all be telly; visual aids.’ ‘Then why are more books published every year?’ Ludo had asked, annoyed with him as usual. ‘Show me the figures, laddie. Show me the figures.’

Elizabeth Taylor, Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, 1971, chap. 9

The total number of all extant and accessible manuscripts in Arabic script is not known (Adam Gacek, Arabic Manuscripts: A Vademecum for Readers, Leiden: Brill, 2009, p. x). Scholars whose research focuses on the history of the book in Muslim societies are of course aware of this fact, and there are at least two rough estimates on the table. Geoffrey Roper (“The History of the Book in the Muslim World,” in The Oxford Companion to the Book, eds. Michael F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, 2 vols., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, vol. 1, p. 323) has recently suggested that “more than 3 million MS texts in Arabic script” have been preserved in accessible collections worldwide, while the number of inaccessible manuscripts in private collections is anybody’s guess. Roper pulled this number out of his hat, providing no explanation whatsoever as to how he derived at it: What (catalogs and internal shelf-lists?) did who (staff or outside researchers?) analyze to determine the holdings of manuscripts in Arabic script all around the world? What was counted (parchment and paper? fragments and complete codices?) and what was excluded (papyri and archival documents on paper?). But Roper’s number is important, because he was the general editor of the World Survey of Islamic Manuscripts (5 vols., London: Furqan, 1991-1994). Moreover, his number is comparable to François Déroche’s estimate of about 4 million extant manuscripts in Arabic script (oral communication, Christoph Rauch, 5 January 2010), though I do not know in which context Deroche has suggested this number. Since an estimate in the millions has an accordingly wide margin of error―for example, 1 percent of 1,000,000 is 10,000―the numbers put forward by Roper and Déroche serve, depending on one’s point of view, as rhetorical sleights of hand or effective didactic devices by adding a fleeting sense of fact-based mastery to the much more low-key observation that there are lots and lots of manuscripts in Arabic script dispersed in public and private collections worldwide. I find remarkable, though, that the estimates by Roper and Déroche leave room for optimism. In the times of big data, collecting cataloging metadata for manuscript holdings in the low single-digit millions should be manageable. Indeed, these holdings in Arabic script seem rather modest if compared to the estimate of more than 30 million Indian manuscripts, written in Sanskrit or vernacular Indic languages and preserved in India alone (Sheldon Pollock, “Literary Culture and Manuscript Culture in Precolonial India,” in Literary Cultures and the Material Book, eds. Simon Eliot et al., London: British Library, 2007, p. 87; for a discussion of the empirical data in incunable research, see Joseph A. Dane, The Myth of Print Culture: Essays on Evidence, Textuality, and Bibliographic Method, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003, in particular chapter 2 on “Twenty Million Incunables Can’t Be Wrong,” pp. 32-56).

Specialists of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies rarely discuss this situation and its impact on all aspects of their research. We take immense pride in the riches of the Islamic manuscript tradition, and yet, we lament about the primary sources actually available for research (R. Stephen Humphreys, Islamic History: A Framework for Inquiry, rev. ed., Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991, p. 25). Although autograph manuscripts are very rare in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, there is no agreed upon process of ratiocination―comparable, for example, to the distinctions between Folio, Good Quarto, and Bad Quarto in Shakespeare Studies―for the compilation of a manuscript corpus that will allow for the preparation of a scholarly edition, whenever a complete census of all known and extant manuscript copies is neither feasible nor possible. In subfields, such as Graeco-Arabic Studies and Papyrology, scholars draw on the editorial theory and practice as developed by Classical Philology. But, in general, research based on manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script remains curiously disconnected from fundamental questions about the material evidence yielded by paleographical, codicological, and bibliographical analysis.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the number of Islamic manuscripts seems as uncountable as the number of Muslims, be it in the US or all around the world, as there is no central organization which can claim authority over the preservation of Islam’s cultural heritage. The international diffusion of manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script reflects the ethnic, linguistic, and denominational diversity of the worldwide Muslim community, and explains why it is so difficult to track Islamic holdings in public and private collections. Muslims, in contrast, for example, to members of the Roman-Catholic Church, do not belong to a faith tradition that unites its believers within a strictly top-down and binding hierarchy. Since the Eurasian, African, and Asian nation states which are ruled by Muslim elites or have a Muslim majority population are currently confronted with much more pressing political and economic problems, it is rather unlikely that an Islamic counterpart to the UNESCO will be established any time soon. The preservation of books and their cataloging must take a backseat when people live in dire poverty and their lives are threatened by sectarian and ethnic violence.

The current state of cataloging manuscripts in Arabic script mirrors this complex political situation. There is a tacit agreement, especially among western scholars of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, to bravely soldier on with individual research projects without sounding a clarion call for concerted action, as such a call will inevitably raise the specter of Orientalism. Professional academic organizations, in particular MELCom International, MELA and TIMA, have made the cataloging of Islamic books, whether manuscripts or printed books, a focus of their work, even though they are fighting an uphill battle. Decades of political pressure on the Humanities in Europe and North America have severely reduced government funding for basic research which does not promise immediate benefits to taxpayers outside the enchanted reading rooms of academia. It is nice to know which books are in the library. But a library catalog does not carry the prestige of original research; nor does it help with paying for new acquisitions, salaries, and building maintenance.

The severe funding shortages faced by private and public institutions have created an opening for wealthy individuals who have made the preservation and accessibility of this or that part of Islam’s cultural heritage their responsibility. The non-profit foundations of their choice exert significant influence over the cataloging of manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script. Since private and public institutions have to make strategic decisions about acceptable funding, sometimes, pecunia olet. The strategic necessity to design feasible projects that can successfully compete for as much acceptable outside funding as possible does not ensure that the most deserving holdings receive the funding needed for their cataloging, as well as for preservation and digitization. As long as the fierce competition for limited funding pits institutions against each other, the absolute merit of an Islamic book collection is less important than an institution’s ability to offer acceptable donors and grant-making agencies the best match for their funding priorities.

In theory, institutions with Islamic manuscripts and printed books have access to experts who determine the merit of uncataloged holdings in Arabic script and select items for cataloging, as well as for preservation and digitization. Even though it seems logical to catalog all known and extant manuscripts and rare printed books before making decisions on those which should, and still can, be digitized, the creation of digital surrogates that are instantaneously made available on the internet irrespective of the quality of their cataloging is often considered a much better investment of limited financial resources. There are obvious benefits to facilitating the digital access to the texts of manuscripts and rare printed books. Digital surrogates are so readily accepted by scholars, because their primary function is that of any other book in any other format or medium: to preserve and display written language. In addition, pretty digital surrogates offer an immediate esthetic gratification on computer screens that is out of reach for highly technical cataloging in a digital database. No one gets excited about access to correct and detailed metadata for manuscripts and printed books, even though poorly cataloged holdings are effectively lost to scholarship. I was told by a Columbia University librarian that it would be impossible to obtain funding for the descriptive cataloging of Columbia’s rare Persian lithographs since these printed books already have records, however faulty and incomplete, in Columbia’s online catalog CLIO and are therefore considered cataloged.

The popular perception of digitization is all about convenience in the service of increased scholarly productivity, since fewer library trips mean less time needed for drudgery and legwork which in turn should increase the time available for working on publications. We happily delegate to our colleagues in Information Science and the Digital Humanities all worries about the long-term preservation of digital surrogates and their long-term interoperability with future electronic databases, portals, or platforms. It is not uncommon on Middle East and Islamic Studies listservices that scholars look for e-books of works in Arabic script, specifying that they would prefer e-books with full-text search. Yet I have never noticed any discussion of TEI and other mark-up languages on these listservices, even though full-text search demands a fully encoded text. After all it would be ungrateful to complain about the steadily growing number of digitized Islamic manuscripts and printed books available for free on the internet.

Appearances, however, can be deceptive. The easy one-click access to previously rare texts in Arabic script on our computer screens is not cost-neutral. On the contrary. It is accompanied by three serious disadvantages. The first is that digital surrogates seem to diminish the intellectual merit of the original artifacts’ descriptive cataloging, since the texts themselves can now be read on the internet. A digital text’s direct accessibility makes the material artifact that allowed for its transmission and preservation invisible, as there is no longer any physical obstacle between the reader and the text. The immediacy of digital surrogates effectively puts an end to the hands-on experience of material books as historical evidence of intellectual practice (David McKitterick, Print, Manuscript and the Search for Order: 1450–1830, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 18-19). The Hathi Trust Digital Library, for example, allows its members to download pdf-files of digitized works in the public domain. But the pdf-file itself will only preserve information about the holding library, without revealing the actual call number (see, for example, the nineteenth-century MS pers. of Vāmiq va ʿAẕrā, University of Michigan Library, Isl. Ms. 1043, cf. the record at Hathi Trust Digital Library at: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015079131705 and the most recent record with comments on the Islamic Manuscripts at Michigan website). The fact that the creators of this academic digital library consider call numbers dispensable suggests that the digital surrogate is seen as a complete replacement of the original book, making any further interaction with the material artifact itself unnecessary. For I do not know of any library where it be possible to request a book without knowing its call number.

The second disadvantage of the easy one-click access to previously rare texts on the internet is the haphazard approach to the cataloging and the digitization of Islam’s cultural heritage. The funding priorities of acceptable donors and grant-making agencies determine feasibility, while the competition for outside funding pits institutions against each other. North American and European depositories favor institutional independence, when courting donors and applying to grant-making agencies, and focus, very sensibly, on clearly circumscribed projects. For small-scale projects with their own dedicated Islamic manuscript portals―examples are the digitization initiatives at the Walters Art Museum Baltimore, Harvard University Library, or the Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig―are more likely to be successfully completed within their grant periods. In contrast, large libraries, such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris (for single pages, see its Banques d’Images), the Bodleian Libraries (for single pages, see their Masterpieces of the non-Western book), or the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich (for complete books, see its Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum), include manuscripts and printed books in Arabic scripts while they are digitizing their most important rare holdings. Whenever Islamic holdings are included into such comprehensive and long-term digitization projects, the quality and the accessibility of their metadata will determine whether in these vast online collections of digital surrogates search engines can retrieve the Islamic holdings.

Occasionally, the initiative of a private donor seems to force a decision which database will receive the digital surrogates of Islamic manuscripts. In May 2012, the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin announced that it will digitize and catalog its collection within an Islamic Art Online portal because Yousef Jameel has provided the funding. This digitization project will include the museum’s manuscripts in Arabic script, and the earlier plan of digitizing the museum’s Islamic books in cooperation with the digitization project Orient-Digital of the Orientabteilung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin has been abandoned (email, Julia Gonnella, 13 June 2012). The situation in Berlin is quite curious since both the Museum für Islamische Kunst and the Staatsbibliothek belong to the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

The haphazard approach to the cataloging and the digitization of Islam’s cultural heritage also reflects that for private donors it is now almost impossible to envision the digital cataloging of artifacts not available as digital surrogates. Since so many manuscripts and printed books have already been digitized, there is enormous pressure on institutions to forge ahead with the digitization of their holdings, as completely as possible. The example of the Collaboration in Cataloging Project of University of Michigan Library documents that it is possible to obtain funding for the digitization of uncataloged manuscripts in Arabic script. Indeed, the undigitized book has become a problem, if not as a serious offense. It is therefore only logical that in the British Library digitization and cataloging are going hand in hand, when private foundations contribute funding to particular projects. In 2011 the British Library embarked on the creation of digital archive for its Persian manuscripts, and this summer the Iran-centered project was supplemented with a digital archive for the British Library holdings concerning the Gulf region. This development is noteworthy because in a parallel move British academic libraries have bandied together to establish Fihrist, a digital union catalog for manuscripts in Arabic script in British libraries. It remains to be seen whether other Western countries will follow suit and emulate the Fihrist model. I suspect that the development of financing models of academic publishing will determine how Islamic manuscript catalogs will be published in the future. In Germany, for example, the project of the Katalogisierung der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland (KOHD), which is now envisioned to be completed in 2015, continues to receive funding for issuing the Verzeichnis der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland (VOHD), as printed hardcovers (email, Tilman Seidensticker, 17 May 2012). Who are the intended audiences of these very expensive German books? For decades German has been losing ground as an academic lingua franca, and only research libraries with generous acquisition budgets can afford standing subscriptions to the VOHD. But be this is as it may, the KOHD sticks to publishing the results of their research in print, as there is no comparable funding available for the creation of digital metadata records, derived from the detailed German descriptions of undigitized Oriental manuscripts.

The pragmatic preference for clearly circumscribed independent cataloging and digitization projects explains why so few specialists bother with keeping track of all the independent databases that contain digital surrogates of manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script. The fierce competition for outside funding provides little incentive for institutional cooperation, and may be a contributing factor as to why there are not yet widely accepted best practices for how to make the digital surrogates of Islamic manuscripts and printed books, as well as their cataloging records, available on the internet. In December 2010, Klaus Graf wondered on his blog Archivalia why he could not find a list of databases with digitized Islamic manuscripts anywhere on the internet; Peter Magierski is now keeping such a regularly updated list of open access databases on his blog AMIR. It remains to be seen whether the decision of grant-making agencies, such as the Humboldt Foundation, NEH, DFG, the Carnegie Corporation of New York, or the Doris Duke Foundation, to prioritize projects that necessitate domestic and international cooperation between institutions will provide an incentive to scholars in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies to invent new models for how to coordinate the cataloging of and access to Islamic holdings in the Digital Age.

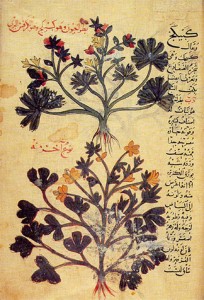

The third disadvantage of easy one-click access to previously rare texts on the internet is that the competition for funding favors holdings which can be presented as exceptional to donors and grant-making agencies. It is of course unfair to accuse any institution for drawing on the importance or artistic value of its holdings in order to attract outside funding. The digitization of Zaydī manuscripts in private collections in Yemen, in connection with the digitization of Zaydī manuscripts in Princeton University Library and the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, is the example of a successful international project that received funding from several sources, as there is a compelling need to preserve cultural heritage threatened by political conflict. But significance, like beauty, rests always in the eye of the beholder. The focus on a particularly endangered group of manuscripts in Arabic script makes it harder to contextualize those holdings, which are now distinguished by having received a substantial grant. Every book refers to other books, and not even the most exceptional book was produced in a vacuum. What will happen to those Yemini manuscripts that cannot be classified as Zaydī? Since every book is a commodity within a society’s system of book production, how is that which has been preserved related to that which was originally produced? In every literate society there are many more cheap books than livres d’artiste in circulation, and yet, expensive books and other collectibles are much more likely to survive.

At this point my considerations have come full circle. As long as specialists of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies have only very rough estimates for the total number of all extant and accessible manuscripts in Arabic script, it is impossible to gain a better understanding of how the bias of survival has shaped, as well as distorted, the available sources of Islamic history. The international dispersion of Islamic manuscripts and rare printed books makes it very difficult to keep track of these holdings and to organize their cataloging. Unfortunately the great attraction of pretty digital surrogates further complicates all efforts to raise money for the little valued, but much more urgently needed cataloging of all known books in Arabic script.

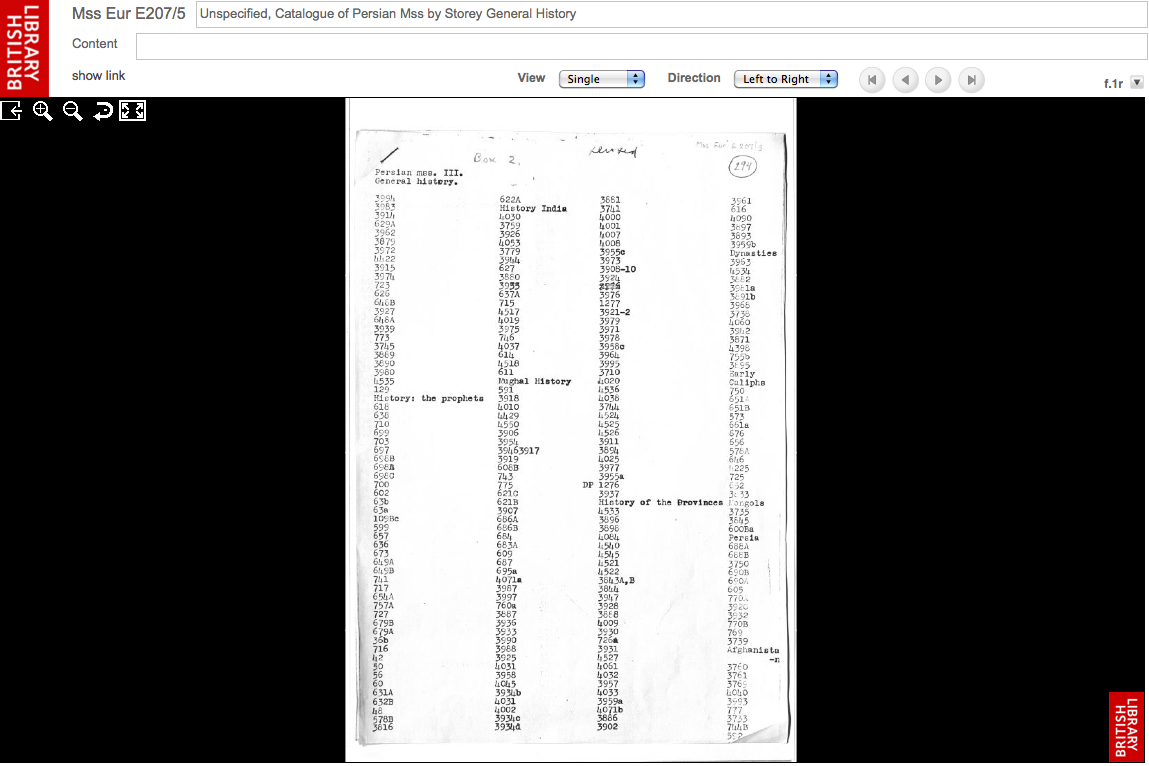

PS. The Iran Heritage Foundation (IHF) has just posted a You Tube fundraising video, providing some figures for its digitization project in the British Library. Its collection of more than 11,000 Persian manuscripts is the largest collection in the Western World, and about 1,370 of these manuscripts are currently cataloged in the British online catalog Fihrist. In the course of the IHF project, the British Library expects to completely digitize another 40 to 50 Persian manuscripts, while adding as many metadata records as possible to Fihrist.

Updated, 13 January 2013.