Undergraduates today can select from a swathe of identity studies: “gender studies,” “women’s studies,” “Asian-Pacific-American studies,” and dozens of others. The shortcoming of all these para-academic programs is not that they concentrate on a given ethnic or geographical minority; it is that they encourage members of that minority to study themselves—thereby simultaneously negating the goals of a liberal education and reinforcing the sectarian and ghetto mentalities they purport to undermine.

Tony Judt, “Edge People,” in The Memory Chalet, 2010

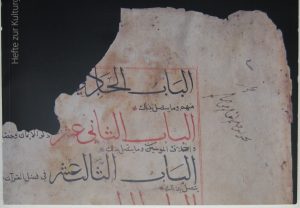

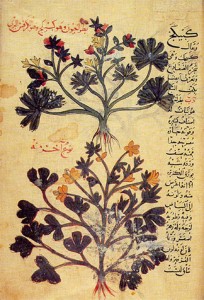

The concept of Islamic books has the significant advantage that it allows for situating research on manuscripts, printed books, and ephemera in Arabic script within the larger fields of cultural and material history. The concept is derived from a definition of Islamic civilization as a catch-all: comprising more than Islam as a faith and reaching beyond the borders of the central Arab lands which are commonly associated with the Middle East. The emphasis on openness is important as a counterweight to any form of essentialism. From the eighth to the fifteenth century CE, Muslim elites ruled over parts of the Spanish Peninsula and Southern Italy, and afterwards the Ottoman Empire expanded into Central Europe and included parts of the Balkans until its demise after World War I. The import of slaves from East and West Africa led to the establishment of the first Muslim underground communities in seventeenth-century North America, even though the savage conditions of slavery ensured that little to nothing has been preserved about these Muslim congregations. Significant Muslim minorities in all societies of Western Europe and North America make it today irresponsible to approach Islam as an exclusively non-Western phenomenon.

It is impossible to predict how in the Western world Muslim citizens will change our research in Middle Eastern, South Asian, Arab, Iranian, Turkish, or Islamic Studies over the next decades. But it seems a reasonable guess that American research libraries will adapt their current collection policies to these continuous transformations since the reigning Area Studies paradigm continues to treat Islamic civilization as mostly Middle Eastern. A map of the world is neatly divided into blocs of twenty-first-century nation states, thereby obfuscating diversity, mobility, and migration in societies past and present, whereas contemporary national languages, in particular Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Urdu, determine whether manuscripts, printed books or ephemera in Arabic script are under the responsibility of an Area Studies specialist for Middle Eastern, African, or South Asian Studies. For Islamic books that were produced before World War I such a language-based classification scheme is spectacularly unsuited. Premodern Muslim societies were multilingual, and Islamic books in different languages circulated widely from India to the Balkans, from West Africa to Central Asia.

How long it will take until American research libraries adapt their collection policies is an entirely different matter. As long as universities continue to organize research on Muslim societies in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa within the Area Studies paradigm, research libraries will follow suit because libraries are strictly hierarchical institutions. Their top-down structure is designed to build and protect collections whose content is determined by bibliographers or curators. Librarians are usually open to their patrons’ input, as there are always more books on sale than there is money for purchases. But the power of the purse makes librarians willy-nilly arbiters of each book’s merit and value. Since the mission of a research library is the furthering of scholarship, not all patrons are equal before the librarians. In the hushed reading rooms, patrons clamor for the librarians’ attention, while the librarians busy themselves with applying to a higher authority in order to stay above the fray. Librarians are bound by both a professional ethos of service and their institution’s hierarchy. When in doubt, librarians will ask professors for advice and consent, and the professors in turn decide the fate of their institution’s library collections ex officio.

The history of Jewish Studies collections in New York research libraries suggests, though, that extra-academic contingencies are more likely to determine whether an American research library will abandon the Area Studies paradigm to gather its diverse holdings in Arabic script as a comprehensively defined Islamic Studies collection. In 1897 Jacob Schiff (1847-1920) initiated the establishment of an Oriental Division at the newly founded New York Public Library (NYPL) to ensure access to a Jewish Studies reference collection in Midtown Manhattan. Since the division’s chief librarian Richard Gottheil (1862-1936) did not get along with his bibliographer Abraham Freidus (1867-1923), the Jewish holdings were separated from the Oriental Division, and in 1901 Freidus became chief librarian of an independent Jewish Division (Phyllis Dain, The New York Public Library: A History of its Founding and Early Years, New York: NYPL, 1972, pp. 116-117). After the Second World War the Oriental Division was renamed Asian and Middle Eastern Division and dissolved, together with the Slavic and Baltic Division, in 2008. In the Columbia University Libraries (CUL), the responsibilities of the Middle East bibliographer used to include Judaica. But a few years ago, when a generous gift had made it possible to establish the Norman E. Alexander Library of Jewish Studies, CUL reorganized its Area Studies Library which continues to include Jewish Studies, and the Middle East bibliographer is now explicitly in charge of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies.

PS. As of Fall 2012, Columbia University Libraries has renamed its Area Studies Library as Global Studies Library. Yet Western Europe and North America, which were not included into the Area Studies Library, are still not aboard.

Updated, 12 September 2012.