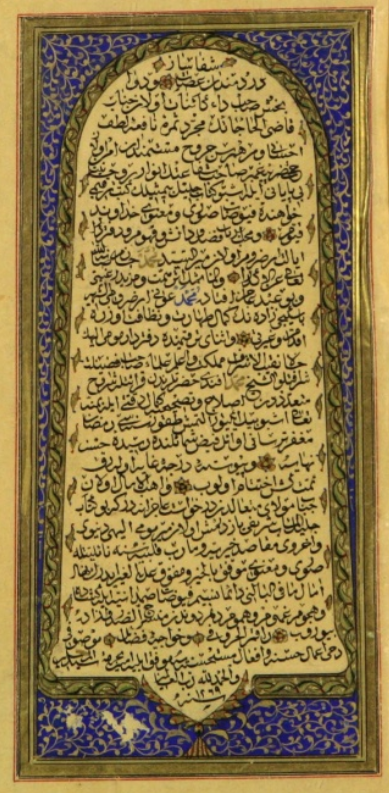

One goal of my Marie Curie research project is to situate the Kitāb al-shifāʾ bi-taʿrīf huqūq al-Muṣṭafā (“The book of healing concerning the recognition of the true facts about the chosen one”), a work about the prophet Muḥammad (d. 632) compiled by the Maliki jurist Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ (1083-1149), within the context of medieval Iberian literature. Taking as starting point the observation that Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, all three faith traditions have literature about prophets, I am co-organizing an international workshop with Benito Rial Costas, a specialist of the book in early modern Spain who teaches at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. The workshop Of Prophets and Saints: Literary Traditions and “convivencia” in Medieval and Early Modern Iberia will take place in Madrid on February 22 and 23, 2018. In the next weeks detailed information about the workshop’s program will be posted on its website. Below follow some thoughts on the workshop’s rationale.

Plate with Jonah and the whale

Tin-glazed earthenware, d = 41 cm, Talavera de la Reina, Toledo, c.1600, HSA LE2407

Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York

The international workshop will explore religious literature that originated under the particular conditions of “convivencia” in the societies of medieval and early modern Iberia. It has twenty participants, eighteen invited colleagues and the two organizers, and will be open to the public. It most general aim is to promote exchange and discussion between academics from Spain with scholars from other parts of Europe and North America. The participants will employ comparative and interdisciplinary approaches to open new perspectives on how the coexistence of Jewish, Christian and Muslim communities on the Iberian Peninsula is reflected in their respective literary traditions. The primary focus will be on works concerning prophets and saints. Both are figures of spiritual authority, since each of the three religions acknowledges prophecy (Heb. nəb̲ūʾa, Lat. prophetia, Ar. nubuwwa) and holiness (cf. Heb. ẓaddik, Lat. sanctus, Ar. walī). The workshop’s starting point is the hypothesis that literature about prophets and saints also reflected changing modes of religious coexistence, because in premodern societies every contact between religions was haunted by the fear that one’s own religion might have followed a false prophet. The long experience of religious coexistence on the Iberian Peninsula—beginning with the Islamic invasion of the Visigothic kingdom (418–c.721 CE) in 711 and changing after the rise of the Almoravid dynasty (1040–1147), the Christian edict of conversion in 1391 and the anti-Jewish riots of 1392—also challenges contemporary notions of the roles of both Judaism and Islam in European societies. Since the Holocaust, there has been a growing recognition of two millennia of Judeo-Christian civilization in Europe and North America. Islam, however, is still seen as “other” and defined as being outside, if not incompatible with, western civilization (Richard Bulliet, The Case for Islamo-Christian Civilization, New York City 2004).

The Historiographical Debate on “convivencia”

In research on medieval and early modern Iberia, the term “convivencia” serves as a shorthand for the fact that in the societies of medieval and early modern Iberia, at least until the fall of the Nasrid emirate of Granada (1230–1492), ruling elites of Muslims or Christians lived cheek to jowl with substantial minority communities of Christians, Muslims, or Jews. Relations between these three communities were complicated, and included many forms of violence. Boundaries between religious communities were nonetheless regularly crossed since the three communities were connected in myriad ways in the realms of politics and economics (e.g., Robert Burns, Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the Crusader Kingdom of Valencia, Cambridge 1984; Thomas Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages, 2d rev. ed., Leiden 2005). Moreover, the relative demographic strength of minority communities vis-à-vis their respective ruling elites was unavoidably accompanied by at least some degree of personal acquaintance with neighbors who belonged to other faith communities (David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence, 2d printing with corrections, Princeton 1996, pp. 21-30).

Whenever Iberian societies are considered together with other Mediterranean societies in Asia Minor, the Levant, and North Africa, the Iberian experiences with “convivencia” appear as ordinary. Jews, Christians, and Muslims were living next to or with each other under varying degrees of asymmetric violence since the emergence of Islam in the seventh century (Gil Anidjar, “Medieval Spain and the Integration of Memory,” in Islam and Public Controversy, ed. Nilüfer Göle, Farnham, Surrey 2013, pp. 217–226, esp. 218). It is only from the vantage point of northwest Europe that the coexistence of Christians, Muslims, and Jews in medieval and early modern Iberia continues to be perceived as exceptional, since from France to the British Isles Christians were far less likely to live with or next to Jewish or Muslim neighbors. Small Jewish communities were few and far between, and most Christians only encountered fictional Muslims in Church teachings and vernacular literature (for the best recent survey of the images of Islam in medieval European Christendom, see John Tolan, Saracens, New York City 2002).

It is therefore salient, though not surprising, that at the beginning of the twenty-first century the meaning of “convivencia” in medieval and early modern Iberia has remained fiercely contested (Manuela Marín, “Historical Images of al-Andalus and Andalusians,” in Myths, Historical Archetypes, and Symbolic Figures in Arabic Literature, eds. Anglika Neuwirth et al., Beirut 1999, pp. 409–421; Kenneth Baxter Wolf, “Convivencia in Medieval Spain,” Religion Compass 3/1, 2009, pp. 72–85). The term most likely first entered Iberian studies in 1918, when Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869–1968), a pioneer of comparative philology and literary history, used the phrase “la convivencia del hispano y el sajón que se reparten, con América, uno de los hemisferios del planeta” (pp. 13–14) in an article about “La lengua española,” written for the first issue of Hispania, the new journal of the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese. But it was his use of “convivencia” in Los orígenes del español (Madrid 1926) that introduced the term into the twentieth-century continuation of the much older debate about the emergence of the modern Spanish language in a multilingual and religiously diverse medieval Iberia and its import for a Roman-Catholic Spanish identity at the core of twentieth-century Spanish nationalism (e.g., Arndt Brendecke, Imperium und Empirie, Cologne 2009; Patricia Hertel, Der erinnerte Halbmond, Berlin 2012).

In contrast, the debates on “convivencia” in Jewish and Middle Eastern studies are deeply informed by historical experiences of persecution and loss, in particular after 1492. In Jewish studies, the term “convivencia” is linked to debates about the limits of acculturation despite the celebration of a thriving Sephardic culture, in particular between the eighth and the twelfth century (e.g., Yitzhak Fritz Baer, History of the Jews in Christian Spain, trans. from the Hebrew by Louis Schoffman, 2 vols., Philadelphia 1961–1966; Seth Kimmel, Parables of Coercion, Chicago 2015). In Middle Eastern studies, “convivencia” under the rule of the Umayyad dynasty of Cordoba (756–1031) is cherished as one of the highpoints of medieval Islamic civilization (e.g., María Rosa Menocal, Ornament of the World, Boston 2002; cf. Bruno Soravia, “Al-Andalus au miroir du multiculturalisme,” in Al-Andalus/España, ed. Manuela Marín, Madrid 2009, pp. 351–365).

Material Evidence of Acculturation

That “convivencia” was accompanied by varying degrees and forms of acculturation is well attested in the arts and literature of medieval and early modern Iberia. Art historians discuss the traditional distinctions between “mozárabe” and “mudéjar” when probing how Christians or Muslims, as well as Jews, under Muslim or Christian rule responded to the cultural norms of their respective ruling elites (cf. exhibition catalogs such as Convivencia, Jewish Museum in New York City, 1992; Caliphs and Kings, Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC 2004). With regard to the uses of language and literacy, extant Romance documents written in the Hebrew or the Arabic script (i.e., Aljamiado) have prompted reflections about diglossia and bilingualism (e.g., Federico Corriente, Diccionario de arabismos, Madrid 1999; David Wacks, Double Diaspora in Sephardic Literature, Bloomington, Ind. 2015; Olivier Brisville-Fertin, “¿Aljamía o aljamiado?,” Atalaya, no. 16, 2016, available at: http://atalaya.revues.org/1791). Stanzaic poetry (e.g., Otto Zwartjes, Love Songs from al-Andalus, Leiden 1997) and frametale narrative (e.g., Karla Nielsen, “Sewing on the Frame,” PhD diss., University of California Berkeley 2010) demonstrate the diffusion of literary genres across the boundaries of religious communities.

The Fear of False Prophets

Religious coexistence, however, presented serious theological and spiritual challenges, as in medieval and early modern societies there was no religious tolerance in the modern sense of the term. The legal concept of a secular society in which the full privileges of citizenship are independent of private religious belief did first become law in the French Civil Code of 1804. In medieval and early modern Iberia, Jews, Christians, and Muslims considered themselves followers of a true prophet who had revealed God’s will, which, in turn, was demonstrated in the well-being of God’s chosen community on earth. Since in all three religious communities prophets were recognized as instruments of divine revelation, there was considerable anxiety about proving the truth of one’s own prophet when exposing the falsehood of rival prophets. Apologetic and polemic works from medieval and early modern Iberia vividly illustrate how the experience of oppression on earth added spiritual insult to physical injury, as it raised the specter that a community’s defeat had been preordained because they were following a false, and not a true prophet (e.g., Mercedes García-Arenal and Fernando Rodríguez Mediano, Un oriente español, Madrid 2010; Paola Tartakoff, Between Christian and Jew, Philadelphia 2012; Ryan Szpiech, Conversion and Narrative, Philadelphia 2013). To minorities at the receiving end, hagiographic literature about the lives of prophets and saints was therefore of great practical value, since it provided guidance and consolation whenever a religious community was ruled by those whom they regarded as followers of a false prophet. By the middle of the thirteenth century, the kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Portugal, and Navarre controlled most of the Iberian Pensinsula, while the Nasrid emirate in Granada only held the coastal lands along the southern Mediterranean. Among Iberian Muslims, the demand for works about the life of the prophet Muḥammad (d. 632) went hand in hand with an exploration of literature about jihad (Ar. jihād lit. “struggle, striving”), and there was intense scholarly debate how hadith ascribed to the prophet Muḥammad (Ar. ḥadīth lit. “narrative, talk”) foretold the fate of their community (Maribel Fierro, “Doctrinas y movimientos de tipo mesiánico en al-Andalus,” in Milenarismos y milenaristas en la Europa medieval, ed. José Ignacio de la Iglesia Duarte, Logroño 1999, pp. 159–175, here p. 160; cf. Javier Albarrán, Veneración y polémica, Madrid 2015). Conversely, the rich Sephardic literature about the Messiah provided its Jewish readers with much sought affirmation of a positive Jewish identity (Benjamin Gampel, “A Letter to a Wayward Teacher,” in Cultures of the Jews, ed. David Biale, New York City 2002, pp. 388–447, here p. 421; cf. Howard Kreisel, Prophecy, Dordrecht 2001).

Comparison and Specificity

It is against this background that the workshop will use literature about prophets and saints from Jewish, Christian and Muslim communities to explore “convivencia” in medieval and early modern Iberia. Its methodological approach is the assumption that context-specific investigations will build strong foundations for a fresh interdisciplinary discussion, since concrete literary examples necessitate terminological precision. This specificity will, in turn, serve as safeguard against the hermeneutic pitfall of projecting any particular meaning of “convivencia” unto the interpretation of these sources about important figures of religious authority, since the “problem is not so much the designations themselves, but rather the generalizations that have arisen in their usage.” (María Judith Feliciano and Leyla Rouhi, “Interrogating Iberian Frontiers,” Medieval Encounters 12, 2006, p. 323).

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 706611.