On 17-18 May 2013, Will Hanley of Florida State University (FSU) led the First Workshop for PROSOP, which was held at Brown University. The workshop was supported by a start-up grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH) and by Brown’s Middle East Studies program. Will is a Middle East historian, and his research has, for example, explored Egyptian legal records from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century CE. As the administrator of the ArchivesWiki of the American Historical Association (AHA), his hands-on experiences with this crowdsourced Wiki are informing his plans for this new Digital Humanities project.

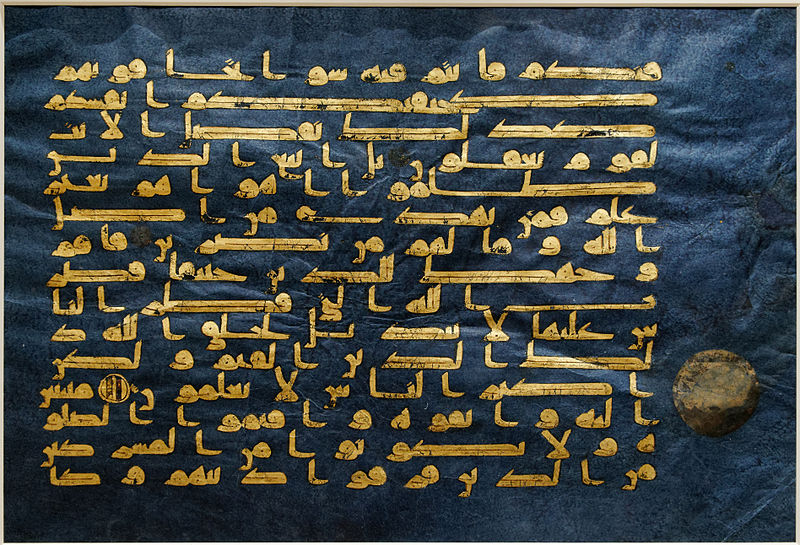

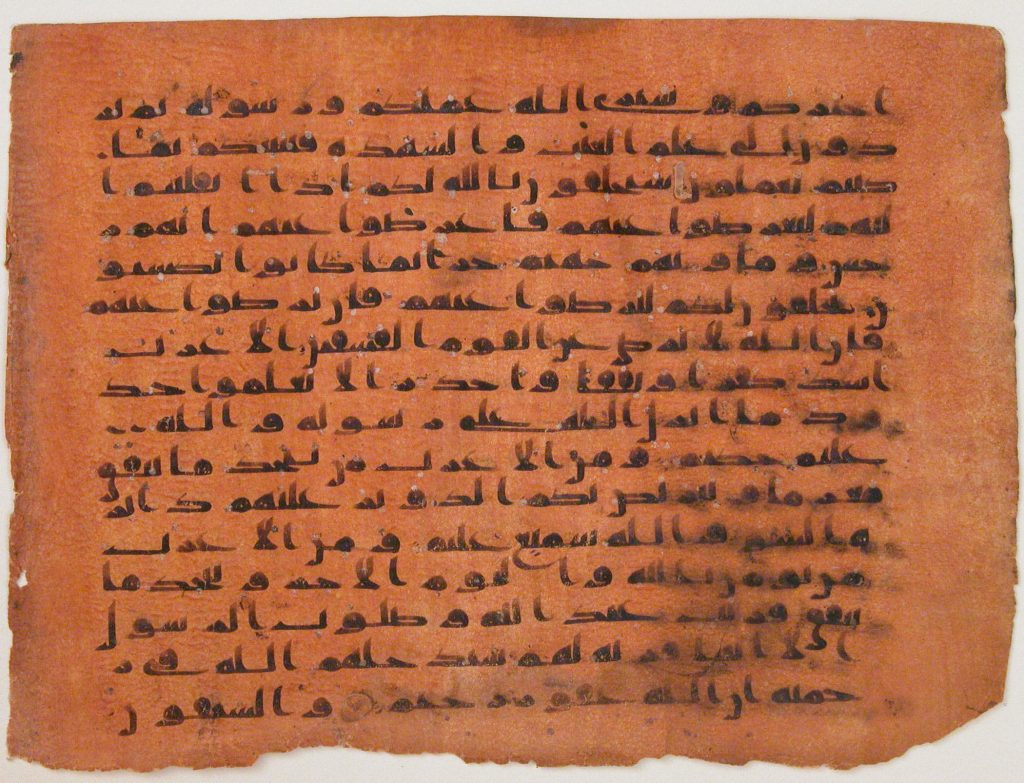

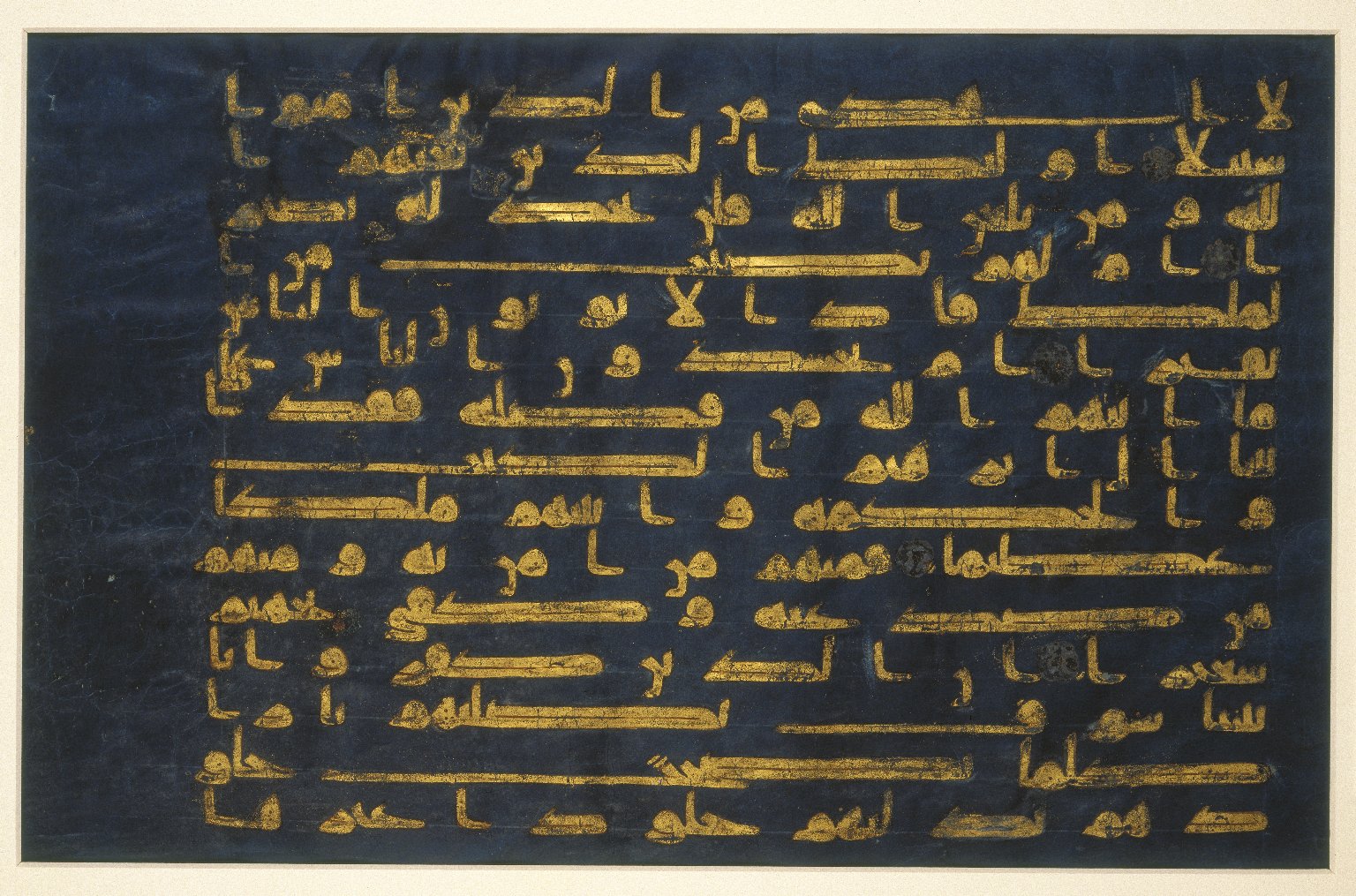

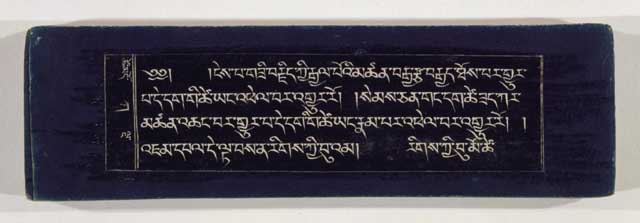

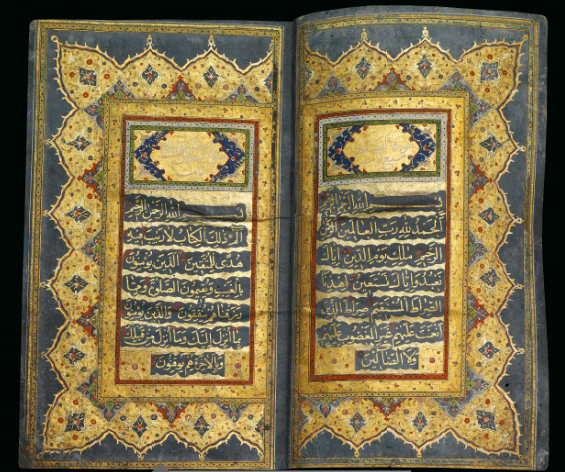

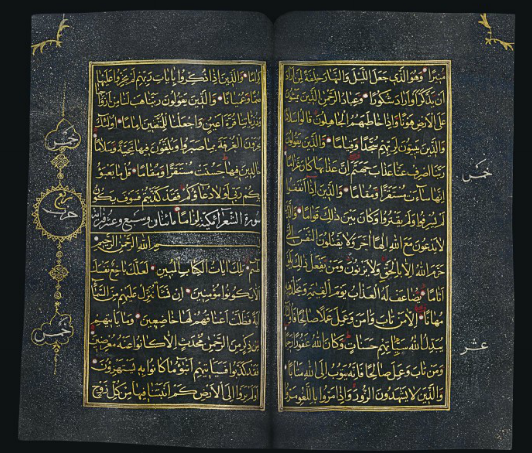

I had applied to the PROSOP workshop because research on manuscripts and printed books in Arabic can yield significant prosopographic knowledge that is not limited to the names of authors. Many books preserve paratexts such as ownership notes, statements about endowments (Arabic sing. waqf), certificates of transmission (Arabic sing. ijāzah), marginal notes (Arabic sing. ḥāshiya), or study and reading notes. The paratexts reveal the names of people related to one specific copy of a written text, such as

• author of a commentary on a specific work

• author of an abridgement or epitome of a specific work

• person who rewrites, revises or edits a specific work

• scribe of a specific copy

• illuminator of a specific copy

• binder of a specific copy

• publisher of a specific copy

• owner of a specific copy (e.g., institution, dealer, private person)

• reader of a specific copy

These names can be examined as concrete historical evidence for the production, circulation, and uses of manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script, providing insight into book production and the book trade as one aspect of the transmission of knowledge in Muslim societies. Considering the overall scarcity of archival sources for the history of premodern Muslim societies, the systematic study of paratexts has the potential to dramatically increase our understanding of the social, intellectual and economic history of Muslim societies. But two formidable obstacles continue to impede the study of paratexts, since few Middle East historians and literary critics are trained in the quantitative research methods commonly applied in the Social Sciences. The first obstacle is the methodological evaluation of an assembled corpus of manuscripts and printed book as a statistically valid sample for both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The second obstacle is the technical skill needed for a meaningful organization of the raw prosopographic data gleaned from paratexts. Consequently, Stefan Leder’s collection of ijāzah from medieval Damascus (Les certificats d’audition à Damas 550 –750 h./1155–1349, 2 vols. Damascus: Institut français d’Etudes arabes & Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, 1996-2000), did not initiate further publications of paratexts from manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script, even though in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies it has been long recognized that paratexts are unique sources of historical evidence. (For more about Islamic books as sources of prosopography, see the notes of my workshop presentation.)

For the PROSOP workshop Will had brought together scholars with very different approaches to prosopography and a wide range of experiences with computer based research and the Digital Humanities. The goal of PROSOP is the aggregation of datasets generated by microhistorical research so that the aggregated datasets can be subjected to macrohistorical analysis (see this 2010 poster illustrating Will’s vision for PROSOP). The need for aggregation reflects the insight that every local event has international and transnational dimensions because all human beings are affected by violent conflicts and trade, whether this impact is consciously recognized (e.g., military engagements, commodity prices, climate change, epidemics) or not. Will himself is right now working with computer scientists on a PROSOP prototype that will provide a website with a template which contributors can adapt to the needs of their specific prosopographic datasets. The site’s search engine will execute global searches across all uploaded datasets. In order to allow for flexibility in such a globally conceived data collection it will be necessary to avoid fixed category requirements, and Will expects that PROSOP will employ the Linked Data framework provided by the Semantic Web.

Will had structured the workshop as a series of presentations about different types of prosopographic datasets. Most of our discussion therefore focused on how the website design and the technical requirements of the database template and its variable fields could be organized in order to accommodate our own idiosyncratic datasets and research needs. With the hope that the debate will continue and that PROSOP will flourish, here are some reflections about PROSOP’s organizational challenges – just my two cents.

PROSOP’s Mode of Operation

Our own reasons for contributing prosopographic datasets to PROSOP indicated that we were interested in submitting datasets to a website that would serve two different purposes: the first is the safe depository for prosopographic research data which are no longer needed for our current work, and the second is an aggregated database whose big data collection promises synergy and serendipity. Accordingly, the PROSOP website should have concise how-to pages for submitting and extracting datasets (cf. the Wiki “Contributing to Wikipedia“), as well as for searching PROSOP and for citing from its datasets and search results.

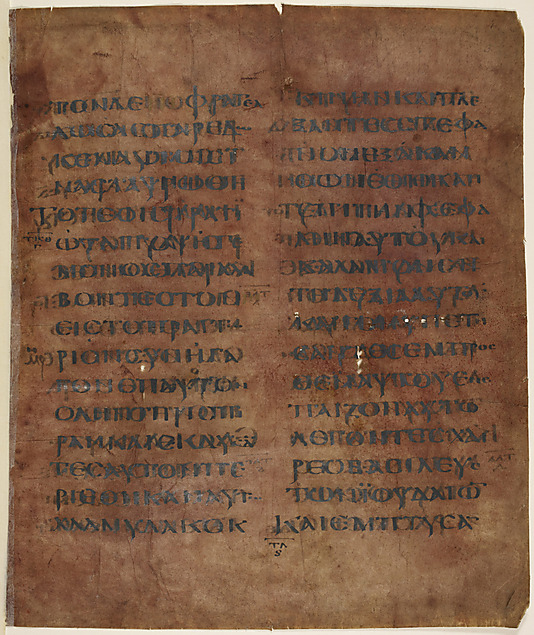

Will is passionate about his commitment that PROSOP be open to all, with no professional barriers to the submission of prosopographic datasets. PROSOP will accommodate the research of bone fida historians and social scientists, as well as the work of genealogists who conduct their historical research as autodidacts and amateurs. This debate was oddly self-referential, as we were discussing the social structure of digital data sharing in order to build a digital repository for social network research data. Will distinguished between data sharing as collaboration among academic peers (e.g., Prosopography of the Byzantine World) and general-audience crowdsourcing, favoring non-commercial general-audience crowdsourcing over strictly academic data sharing (e.g., Open Context). But in fields such as Anglo-Saxon literature and cuneiform studies, the interpretation of relatively scarce and arcane documents demands a high degree of scholarly expertise which in turn exerts a tyranny of quality over any collaborative project. Nonetheless, a site open to all is bound to raise considerable anxiety, not only among contributing academics but also among those individuals and organizations whose funding will keep the project running, about the reliability of the submitted datasets. During our discussion the Americanists were most eager to keep PROSOP accessible to researchers outside academia, as for them the painstaking genealogical research of autodidacts and amateurs is an enormously valuable resource (see Gordon S. Wood, “In Quest of Blood Lines: Review of François Weil’s Family Trees: A History of Genealogy in America,” New York Review of Books, 23 May 2013), even if much of this extramural research primarily generates fuzzy data (see Peter Hajek, “Fuzzy Logic,” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2002, rev. 2010).

The two crucial issues for PROSOP’s mode of operation are the recruitment of collaborators and the site’s concrete uses, while the functional questions of how datasets be entered, stored, and extracted can be treated separately as a technical challenge. Throughout the workshop we did not worry much about how to win active participants from all walks of life; after all, we ourselves were willing to give PROSOP a chance. Will, however, had thought hard about the issue, which he addressed by highlighting the concrete scholarly benefits of data sharing. My own sense of the situation is that the acceptance of and engagement with the project will depend not only on the site’s research utility but also on PROSOP’s association with professional organizations and its institutional ties, since both will directly impact the project’s social prestige in the academic community. (For more thoughts about the social history of knowledge production, see my 2010 conference paper about the Encyclopaedia Iranica).

Will envisions PROSOP as a project without any top-down quality control so that possible contributors without formal credentials would not be scared off or censored. But even a bottom-up project such as Wikipedia has a rating system for entries, and Will therefore insisted that all datasets in PROSOP will receive a “confidence score.” The group accepted as practical and efficient the device of a straightforward questionnaire with control questions which would allow for a modicum of critical evaluation. The questionnaire would ensure that contributors describe and evaluate datasets prior to their submission to PROSOP. I found salient that among a group of Humanities scholars there was a clear preference for a computer’s judgment calls. Most of us had no problem with surrendering the final judgment of their datasets to an algorithm that would calculate the results of the questionnaire as a dataset’s numerical confidence score. While I am still surprised by this trust in an algorithm, the preference may reflect the perception that a computer is less fallible and more transparent in its decisions than a (human) editor.

PROSOP’s Professional Associations

In order to provide Will’s vision of a continually growing international website with additional support, it seems to me that PROSOP would benefit from being already in this early stage more closely linked to professional associations, even if these associations would come at the prize of an additional layer of administrative duties. As a project that Will single-handedly started in the USA it would seem logical to approach the professional organizations of American historians, archivists, and librarians, while reaching out to the Library of Congress (LoC) and the National Archives and Records Administrations (NARA). The conversation opener could be the fact that Will has received the blessings of a NEH start-up grant for PROSOP, while the concrete matter at hand would be the formal establishment of an advisory board, or something similar (cf. the division of labor among the collaborators of the Social Network and Archival Context Project). The AHA may be of particular importance to PROSOP since the AHA does not limit its membership to academics. How many of the workshop participants were, for example, AHA members in good standing? In addition, the AHA has been actively engaged in fostering Digital History for more than a decade, and among its members are historians from other countries and continents.

PROSOP’s Institutional Ties

At the moment, PROSOP has a freestanding website at http://www.prosop.org. In order to guarantee the secure storage of datasets contributed to PROSOP it seems necessary to plan already during the development phase for secure and regular backups of the site’s continually growing contents as well as for mechanisms that will allow for the uploading of datasets, the downloading of the template, and the extraction of individual datasets. The secure storage of the uploaded datasets will be one of the incentives for contributing to PROSOP, but the secure storage presents a technical challenge because PROSOP will not merely aggregate a huge collection of individual files saved as text, PDF, or spreadsheet. Since successful collaborative Digital Humanities projects such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (http://plato.stanford.edu/) or the Social Network and Archival Context Project (http://socialarchive.iath.virginia.edu/) are hosted on university servers, the question arises whether PROSOP would also benefit from an explicit institutional link with FSU where Will is a professor in the History Department.

PROSOP’s Model of Financing

PROSOP’s future depends on its financial viability. Irrespective of where the website be hosted on the Internet, the maintenance of an actively growing website, which is designed as a digitally-born resource, is cost- and labor-intensive. Columbia University Libraries, for example, only accepts active, web-based research projects, if a project has its own endowment dedicated to covering all costs associated with hosting the associated websites. Aside from the daily maintenance costs which range from electricity to salaries for technicians, money will be needed for a separate research and development (R&D) team so that there will be regular updates to PROSOP’s underlying technology and visible web interface. While the NEH stipulates that its projects are available as Open Access resources since they have received financial support from the US government, it may be worthwhile to explore not only the options of fundraising for a dedicated endowment and of an institutional sponsorship program (cf. the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy International Association) but also the possibility of cost-recovery for nonprofit institutions (e.g., the secure storage of prosopographic research data; cf. that in the US the libraries of nonprofit colleges and universities rely on cost-recovery to give students and faculty affordable access to very expensive services such as InterLibraryLoan).

PROSOP’s Copyright and Licensing

The current version of the PROSOP website does not have any statement about the site’s copyright and licenses. Considering the importance of copyright laws for education and research in the US, it may help with the further development of PROSOP if at least the most basic copyright and license issues are addressed, while the first PROSOP prototype is still under development. It is my understanding that Will’s contract with FSU as well as the stipulations of his NEH grant are relevant for determining the copyright of the website and the database design. But I would otherwise expect that Creative Commons licenses should be able to solve most of the copyright issues related to the prosopographic datasets. It may provide an additional incentive for the collaboration with PROSOP if the website has a section which explains, for example, the intellectual property rights of a researcher’s own datasets, or the legal status of prosopographic research based on archival documents and artifacts that are not in the public domain. Since the goal of PROSOP is the aggregation of of the greatest number of available prosopographic datasets, it may not be possible, though, that collaborators can freely chose a particular Creative Commons license for their individual datasets. In any case, the section about PROSOP’s section about copyright and licensing should be clearly linked to the how-to page about citing from PROSOP’s search results and datasets.

PROSOP’s Design

The debates about the design of PROSOP’ interface and database template were particularly fascinating because they revealed the extent to which knowledge production and knowledge transmission is culturally determined. Some favored a user-friendly simple interface design, while others asked for truth in advertising, insisting that no glossy layout be used to hide the nitty-gritty complexity of a serious dataset template. There was, however, agreement that it be important that there be as few clicks as possible between the homepage and the search form or a particular dataset.

Within the group there were still some proponents for developing PROSOP as a relational database, even though Will and his computer science collaborators have already rejected this option. Another recurrent theme in the discussion was the question whether a person’s name or a person’s association with a specific place and time would be the primary categories for organizing the prosopographic datasets. This question strikes me as particularly important, since Will expects that PROSOP will allow for the spatial mapping of search results.

Since I myself I have no practical experience with the setting up of databases, I have no specific wishlist for PROSOP’s database design. But I am very much looking forward to the first PROSOP prototype going live so that I can start using its database template for my research on the production and trade of manuscripts and printed books in Arabic script.

PROSOP and the Ethics of Humanities Research in the Digital Age

Most of our discussion was taken up with very concrete questions about the quantitative and qualitative analysis of prosopographic research data. Conversely, we had little time and energy left for a more general reflection on PROSOP within the concrete political and social realities of the second decade of the twenty-first century. Of course, Will’s decision that PROSOP will not rely on relational database design is based on his philosophical rejection of essentialist categories in historical research. My most general expectation is that PROSOP will manage to remain as transparent as possible about its organization, its funding, and its collaborators. In addition to an active outreach to genealogists and scholars outside North America and Europe, I would find particularly important that the future development of PROSOP will take into account its carbon footprint and the digital divide inside and outside the US.