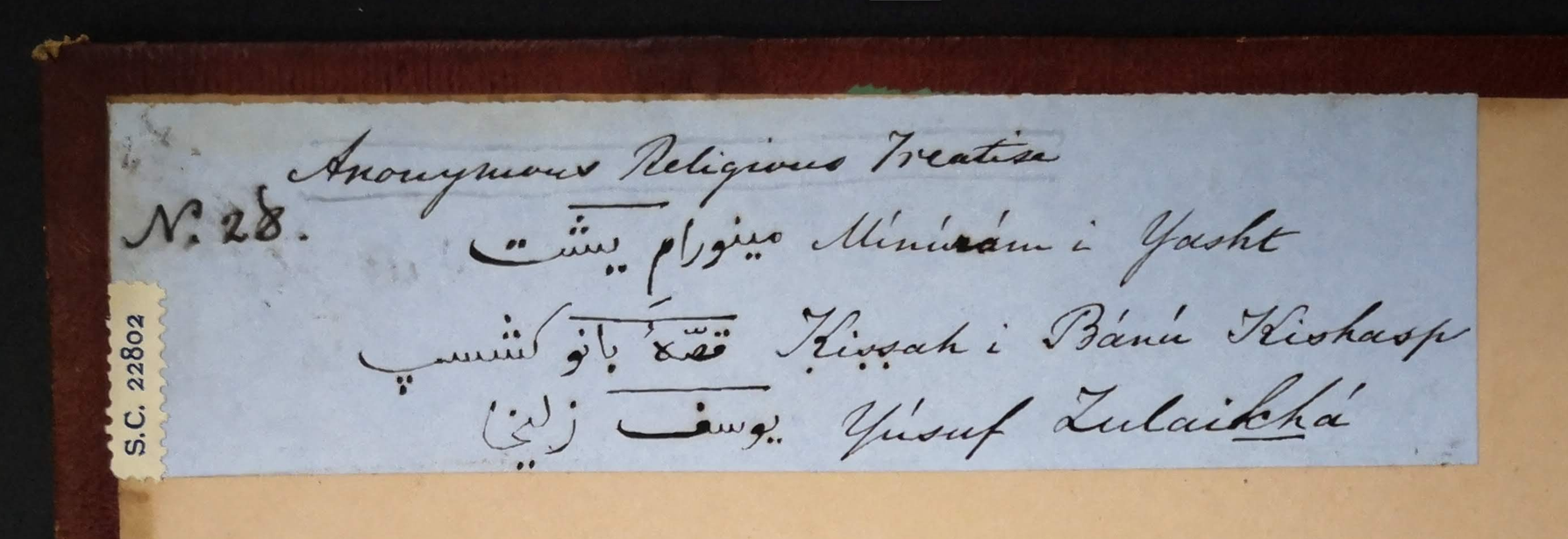

William Ouseley’s label for an undated miscellany, pasted unto the front board’s inside of MS pers. Bodl. Ouseley 28, h = 20.5 cm

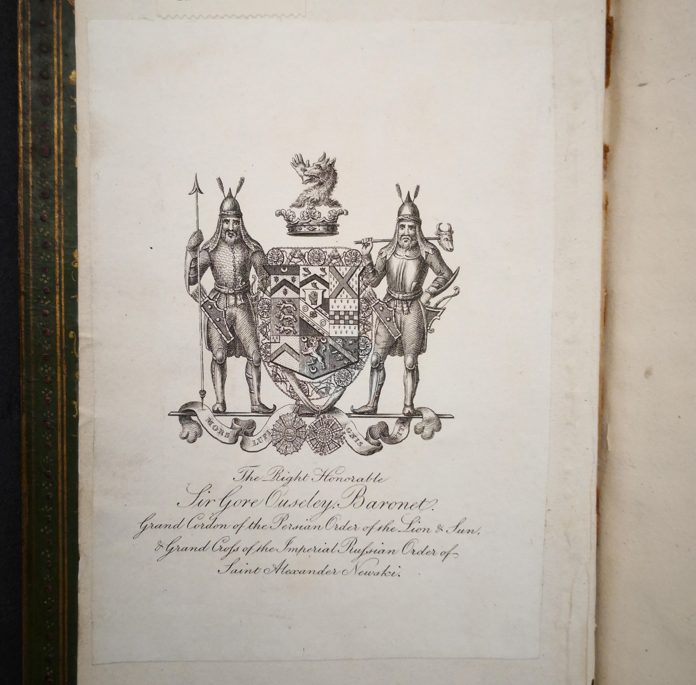

Gore Ouseley’s undated exlibris, from a fly leaf in one of his copies of Saʿdī’s Kullīyāt, MS pers. Bodl. Ouseley Add. 39, dated 856 H./ 1452, h = 21 cm

In March 2022 I was awarded a Bahari Visiting Fellowship in the Persian Arts of the Book at the Bodleian Libraries, which I will hold from 2 May to 1 August 2023. In support of my Bahari fellowship project I received a minor grant from the Oxford Bibliographical Society (OBS) and a grant form the Persian Heritage Foundation (PHF), as well as a non-stipendary Visiting Fellowship at St. Edmund Hall for Michaelmas Term 2022. I owe many thanks to Jake Benson, Susan Boynton, Richard Bulliet, Manuela Ceballos, Elizabeth Evenden-Kenyon, Lalla Rookh Grimes, Henrike Lähnemann, and Marina Rustow for their support of this project. Here follows the report which on 27 February 2023 I submitted to the OBS.

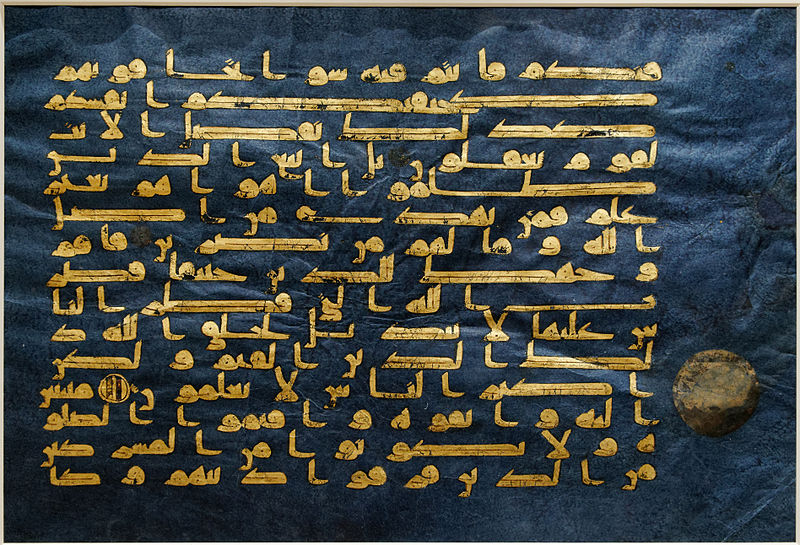

My Bahari fellowship project draws on the Bodleian’s Persian manuscripts of the Anglo-Irish orientalists Sir William Ouseley (1767-1842) and his brother Sir Gore Ouseley, bt (1770-1844). William pursued between 1788 and 1794 a military career with the Royal Dragoons, and then focused on Persian studies. In contrast, Gore lived from 1787 until 1805 as an independent business man in India. He led from 1810 until 1815 – with William as his private secretary – a British diplomatic mission to Tehran and St. Petersburg to assist with the Golestan Treaty negotiations between Iran and Russia. Although the brothers today are celebrated for their bibliophilic codices (e.g., Shāhnāma MSS Bodl. Ouseley Add. 176 and Ouseley 369), most Ouseley manuscripts are devoid of any illumination or figurative painting. The brothers bought Persian texts to study Persian literature, and this lifelong passion is reflected in their publications: William’s Persian Miscellanies (1795, ESTC T154204) is the first English language essay about Persian paleography, and Gore’s Biographical Notices of Persian Poets (Oriental Translation Fund, 1846) is a literary history, compiled from translated Persian sources. When between 1843 and 1859 the Bodleian acquired, through different channels, about 1,000 Ouseley manuscripts, they became an influential resource for Persian studies in Britain. The perhaps most famous example is William’s copy (Bodl. Ouseley 140, dated 865 H./1460) of the divan of ʿUmar Khayyām (1048-1131), which served as a source text for Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát (1st ed. 1859), thereby making the Saljuq mathematician one of the best-known Persian poets in English translation.

The Bodleian’s Ouseley collection is a representative sample for the international trade with Persian books during the Georgian era. After the 1757 battle of Palashi (Plassey) in West Bengal, the expansion of the East India Company’s economic influence was accompanied by an increasing British demand for Persian literature, as well as for Arabic, Urdu, Hindi, or Sanskrit literature. In the book trade in India and Iran this British demand created a secondary, antiquarian market which catered to foreigners. As local and foreign buyers possessed different levels of both familiarity with the canons of oriental literature and expertise in the oriental arts of the book, damaged books which sophisticated local patrons would reject could still be sold to inexperienced foreign customers. These British purchases were manuscripts, since commercial Muslim workshops only transitioned from manuscript copying to printing from the 1820s onwards.

Against this backdrop I argue that the materiality of the Ouseley manuscripts, in particular codicological evidence of repairs and recycling, reflects a stratified book trade in India and Iran. Books are three-dimensional mobile objects with a limited lifespan, because wear-and-tear will eventually destroy every book, however precious. But a damaged book may be preserved, if its presumed market value justifies repairs or recycling as economically sensible interventions. The damaged book’s intended reuse will, in a second step, determine the application of repair or recycling strategies. While these interventions may, or may not, alter a book’s written content, they often destroy copy-specific evidence, such as paratexts which could have allowed for a historical contextualization of its written content’s diffusion.

The overarching goal of my Bahari fellowship project is to highlight the agency of Indian and Iranian dealers at the intersection between book production and the international antiquarian manuscript trade by demonstrating the impact of their material interventions on the textual transmission of Persian literary sources. The codicological analysis reveals fragmentation and reconstruction as complementary strategies with crucial significance to editorial criticism: e.g., Bodl. Ouseley 131 and Ouseley 141, as well as Ouseley 140 with ʿUmar Khayyām’s divan, are fragments of a lost poetic anthology from Turkmen Shiraz, while Bodl. Elliot 5 is a ghost as the composite codex, built up from recycled Akbarnāma fragments, offers an incomplete unique text.

Corrected, 13 March 2023