Researchers have discovered a pathway in the brain that may dictate whether we decide to interact with a friend versus a stranger. “Corticotropin-releasing hormone signaling from prefrontal cortex to lateral septum suppresses interaction with familiar mice”, was published this month in the highly regarded journal Cell. The paper emerged from a collaboration between scientists at the Zuckerman Mind Brain & Behavior Institute at Columbia University and colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington and the Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH in Alicante, Spain. Columbia postdoc Ramon Nogueira contributed to the work.

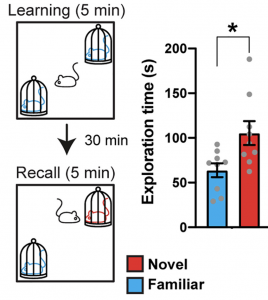

Social novelty preference in mice was first described in the scientific literature 20 years ago, and it is regularly used to assess social memory for research purposes. A typical mouse, when presented with a mouse it knows and a stranger, will spend more time with the familiar mouse (Fig. 1). Until this paper was published, it was unclear what brain regions or pathways influence whether mice choose to interact with novel or familiar mice. Scientists theorized that the lateral septum, a relay center that connects regions of the brain associated with thinking and memory, and the prefrontal cortex, which controls decision-making, might play a part in the social novelty preference. Both regions are also known to be involved in social behavior, and evidence suggested that there may be a neural pathway leading from the infralimbic area (ILA) in the prefrontal cortex to the rostral lateral septum (rLS), a specific region within the lateral septum. The researchers set out to determine how these two regions interact with each other and whether this interaction plays a role in social novelty preference.

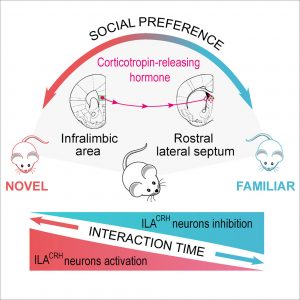

Using a comprehensive and elegant set of experiments to manipulate neuron function in the two regions, the researchers discovered that a population of inhibitory neurons in the ILA connects to the rLS, and that this pathway is crucial for the mice to exhibit the typical social novelty preference. The ILA neurons contain the neurotransmitter corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which is best known for its role in stress and anxiety. Neurons in the rLS have receptors for CRH, but it was previously not known that CRH-containing neurons in the ILA communicate with CRH-receiving neurons in the rLS. When the researchers inactivated the CRH-containing neurons in the ILA, they found that mice failed to exhibit the typical social novelty preference. Next, they asked whether the CRH-receiving neurons in the rLS were also necessary for social novelty preference. They found that removing the CRH receptors from these neurons erased the social novelty preference, just like inactivating the CRH-releasing ILA neurons. Finally, they recorded the activity of CRH-releasing ILA neurons and saw that these neurons were more active when interacting with a familiar mouse than a novel mouse, indicating that these neurons act on the rLS to discourage interactions with familiar mice.

To further probe the relevance of this pathway to social dynamics, the researchers assessed whether CRH may be responsible for the social novelty preference appearing in young mice. While adult mice prefer to interact with novel mice, mouse pups less than two weeks old prefer to interact with their mothers and littermates rather than unknown adult females or pups from other litters. During this same developmental time period, the population of CRH-releasing neurons that connect to the rLS steadily grows. When CRH was depleted from these neurons, the young mice failed to exhibit the typical shift from a preference for social familiarity to a preference for social novelty. This may be an evolutionary mechanism that encourages young mice to stay in safe, familiar environments, then emboldens adult mice to explore novel environments, collect food, and procreate.

While the social novelty preference in mice does not have a direct analogue in humans, this research may provide clues for understanding and treating social anxiety disorders and social phobias. The human prefrontal cortex and septal regions also respond to social information, and CRH is known to be involved in anxiety disorders including social phobias. The researchers suggest that low CRH levels in the prefrontal cortex may prevent people from seeking social novelty, and that this mechanism could be responsible for social anxiety disorders. The field of neuroscience is just beginning to understand the biological underpinnings of social interaction, and new methods give scientists ever expanding ability to learn about this exciting field.

Reviewed by: Trang Nguyen and Martina Proietti Onori