Half of all children in the United States have been physically assaulted in their lifetime, according to a 2014 study. This finding is alarming, especially considering that childhood maltreatment and abuse can lead to numerous negative mental health outcomes.

Researchers and medical professionals around the globe often focus on adverse childhood experiences and their detrimental effects on development. Experiencing threat and violence is frequently correlated with a decreased ability to effectively handle negative emotions and heightened emotional reactivity relative to those who have not experienced such trauma. For instance, a typical situation such as having your toy taken away by a peer in school might invoke an explosive, angry response from a child who has been a victim of abuse. Moreover, research demonstrates that children who have faced abuse are also more likely than others to interpret ambiguous actions (such as a classmate accidentally bumping into them in the hallway) as confrontational.

How might those who’ve experienced violence in their childhood, and also have trouble dealing with negative emotions, respond to everyday stressors (i.e. getting through hard homework sets or dealing with long waits for customer service on the phone)? Dr. Charlotte Heleniak and her colleagues studied this response, called distress tolerance, in a newly published paper.

Levels of distress tolerance vary among different individuals. Someone with low distress tolerance is extraordinarily uncomfortable in situations where they’re facing a challenging obstacle, upset, or experiencing negative emotions that can make it hard to persist in the face of difficulty. They have a harder time working through these difficult events compared to people with higher distress tolerance. Research also shows that people with low distress tolerance may find it necessary to escape bad feelings by seeking immediate relief. This relief can often take the form of substance abuse.

Additionally, while little research has been done, distress tolerance may make an individual more vulnerable to other mental health problems such anxiety and depression. Because of this, Dr. Heleniak’s team examined whether low distress tolerance is associated with these two mental illnesses, as well as alcohol abuse.

Propensity toward problematic alcohol use in adolescents involves many environmental risk factors such as sociodemographic factors and parental drinking behavior. These can be difficult or impossible to address therapeutically. However, if distress tolerance is indeed tied to substance abuse, this may offer a clearer path toward crafting a psychological intervention.

Dr. Heleniak and her colleagues studied 287 16- to 17-year-old participants across a broad range of socioeconomic backgrounds. They asked the teens about previous violence exposure in their personal life, and assessed depression, anxiety, and alcohol use. Four months later, they reassessed these parameters.

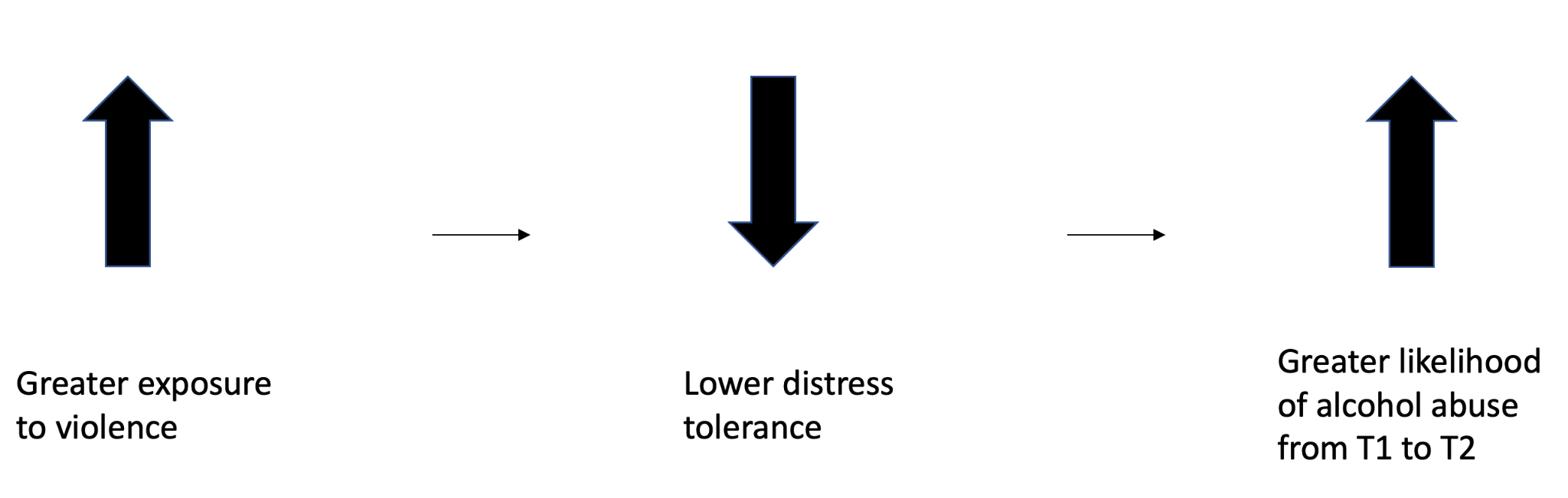

To examine the teens’ distress tolerance, the researchers used a measure called the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task, which measures a person’s persistence on a difficult task. The sooner a participant decides to terminate the task, the lower their distress tolerance. The team found that those teens who experienced a heighted amount of violence did indeed have lower distress tolerance. At the initial time point, lower levels of distress tolerance were not associated with any of the three psychopathologies (i.e. alcohol abuse, anxiety, depression).

However, the researchers found that low distress tolerance predicted alcohol abuse from the first time point to the second, about 4 months later. Low distress tolerance was not associated with anxiety or depression at either of the two time points of data collection.

Based on their findings, Dr. Heleniak and her team conclude that researchers could potentially pinpoint distress tolerance as a way to target teens’ problematic use of alcohol, especially those who have experienced violence. Indeed, therapeutic programs aimed at improving distress tolerance already exist. The authors explain that treatments such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) and mindfulness practices may be particularly useful.

Given that teen alcohol abuse may continue into adulthood and lead to dependency issues later in life, the findings of this study could go a long way to helping those adolescents who struggle with both addiction issues and an abusive past.

If you or someone you know is experiencing substance dependency problems, SAMHSA (1-800-662-HELP) is a free, confidential, resource available 24/7 365-days a year.

Charlotte Heleniak is a postdoctoral scientist in the Developmental Affective Neuroscience Lab at Columbia University. She received her Ph.D. in Child Clinical Psychology from the University of Washington. She focuses on how childhood adversity impacts emotion regulation and social cognition in ways that predict adolescent psychopathology. This research has earned her awards from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, as well as the Sparks Early Career Grant from the American Psychological Foundation.