Plasmodium falciparum is a unicellular organism known as one of the deadliest parasites in humans. This parasite is transmitted through bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes and causes the most dangerous form of malaria, falciparum malaria. Each year, over 200 million cases of malaria result in hundreds of millions of deaths. Moreover, P. falciparum has also been involved in the development of blood cancer. Therefore, study of malaria-causing Plasmodium species and the development of anti-malarial treatment constitute a high-impact domain of biological research.

Antimalarial drugs have been the pillar of malaria control and prophylaxis. Treatments combine rapid compounds to reduce parasite biomass with longer-lasting drugs that eliminate surviving parasites. These strategies have led to significant reductions in malaria-associated deaths. However, Plasmodium is constantly developing resistance to existing treatments. The situation is further complicated by the spread of mosquitoes resistant to insecticides. Additionally, asymptomatic chronic infections serve as parasite reservoirs and the single candidate vaccine has limited efficacy. Thus, the fight against malaria requires sustained efforts. A detailed understanding of P. falciparum biology is still crucial to identify and develop novel and efficient therapeutic targets.

Recent progress in genomics and molecular genetics empowered novel approaches to study the parasite gene functions. Application of genome-based analyses, genome editing, and genetic systems that allow for temporal regulation of gene and protein expression have proven to be crucial in identifying P. falciparum genes involved in antimalarial resistance. In their recent review, Columbia postdoc John Okombo and colleagues summarize the contributions and limitations of some of these approaches in advancing our understanding of Plasmodium biology and in characterizing regions of its genome associated with antimalarial drug responses.

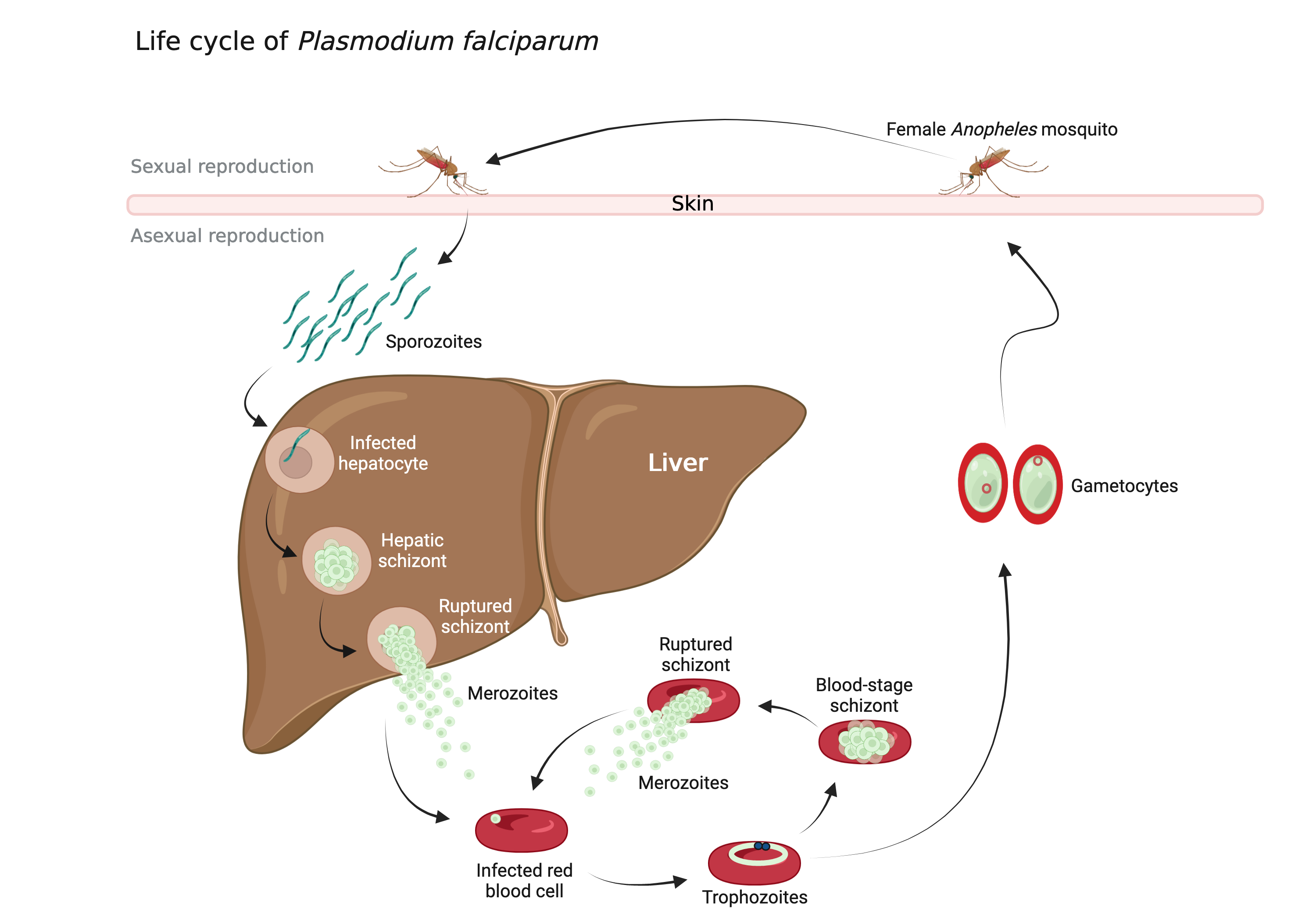

P. falciparum requires two hosts for its development and transmission: humans and Anopheles mosquito species. The parasite life cycle involves numerous developmental stages. In humans take place stages of Plasmodium’s development that are part of its “so-called” asexual development. On the other hand, mosquitos harbour other stages of the parasite development, associated with its sexual reproduction (Figure 1). Humans are infected by a stage called “sporozoites” upon the bite of an infected mosquito. Sporozoites enter the bloodstream and migrate through to the liver where they invade the liver cells (hepatocytes), multiply and form “hepatic schizonts”. Then, the schizonts rupture and release in the circulation the stage of “merozoites” which invade red blood cells (RBCs). The clinical symptoms of malaria such as fever, anemia, and neurological disorder are produced during the blood stage. In RBCs are formed “trophozoites”, that have two alternative paths of development. They can either form “blood-stage schizonts” that produce more RBC-infecting merozoites or can alternatively differentiate to sexual forms, male and female “gametocytes”. Finally, gametocytes get ingested by new mosquitoes during blood meal where they undergo sexual reproduction forming a “zygote”. The zygotes then pass through several additional stages until maturation to a new generation of sporozoites, closing the parasite life cycle (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. Image created with BioRender.com

Figure 1: Life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. Image created with BioRender.com

This complexity of the Plasmodium life cycle presents opportunities to generate drugs acting on various stages of its development. The review of Okombo and colleagues underlines how new genomic data have enabled the identification of genes contributing to various parasite traits, particularly those of antimalarial drug responses. The authors recap genetic- and genomic-based approaches that have set the stage for current investigations into antimalarial drug resistance and Plasmodium biology and have thus led to expanding and improving the available antimalarial arsenal.

For instance, in “genome-wide association studies” (GWAS), parasites isolated from infected patients are profiled for resistance against antimalarial drugs of interest, and their genomes are studied in order to identify genetic variants associated with resistance. In “genetic crosses and linkage analyses”, gametocytes from genetically distinct parental parasites are fed to mosquitoes in which they undergo sexual reproduction. The resulting progeny are inoculated into humanized human liver-chimeric mice-models that support P. falciparum infections and development. The progeny is later analyzed to identify the DNA changes associated with resistance and drug response variation. In “in vitro evolution and whole-genome analysis” antiplasmodial compounds are used to pressure P. falciparum progeny to undergo evolution to drug-resistant parasites. Their genome is then analyzed to identify the genetic determinants that may underlie the resistance. “Phenotype-driven functional Plasmodium mutant screens” are based on random genome-wide mutation generation and selection of mutants that either are resistant to drugs or have affected development, pathogenicity, or virulence. Such an approach has also led to the discovery of novel important genes. In addition, the review covers a number of cutting-edge methods for genome editing used to study antimalarial resistance and mode of action. Experiments using genetically engineered parasites constitute a critical step in uncovering the functional role of the identified genes. Finally, the reader can also find an overview of Plasmodium “regulatable expression strategies”. These approaches are particularly valuable in the study of non-dispensable (essential) genes. Additional information on other intriguing and powerful techniques are further described in the original paper.

Article reviewed by: Trang Nguyen, Samantha Rossano, Maaike Schilperoort