Dancing can be one of life’s greatest pleasures. But for folks who consistently engage in intensive forms of dance, such as ballet, it can also lead to injury. One injury amongst dancers and other athletes is flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy.

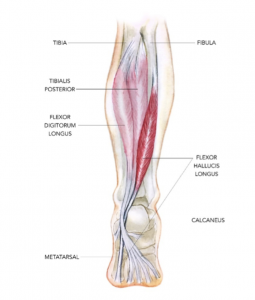

The flexor hallucis longus tendon (FHL), as seen in Figure 1, helps stabilize a person when they’re on their toes and mainly moves to flex the big toe. It stretches all the way from the calf muscle, through the ankle, down to the big toe. When athletes engage in repetitive movements that recruit their foot and ankle in this manner, like jumping up and pushing off the big toe, strain of the FHL tendon can occur. FHL tendinopathy is painful and can leave dancers and gymnasts out of commission from their passion and profession.

Luckily, researchers study overuse conditions like this one. Dr. Hai-Jung Steffi Shih and her colleagues recently published a study where they had 17 female dancers (9 with FHL tendinopathy and 8 without) perform a specific ballet move called saut du chat. The dancers wore a full-body marker set that allowed the researchers to capture the fine-grained positions and movements of the dancers’ bodies throughout the ballet move.

When performing a movement like the saut du chat, the body tends to place a heavy load on one particular joint in the foot called the metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP). Repeating the movement like this over and over again (as dancers often do), can contribute to overuse of the FHL. Researchers can measure something called stiffness in an athlete’s musculoskeletal system to assess the potential for injury. Scientists think that greater stiffness may lead to impact on a person’s bone, while reduced stiffness may lead to soft tissue injury. To better understand stiffness, it can help to think about parts of the lower body as springs, such as the ankle, knee, and hip joints. They compress, store energy, and then release – like when you squat and jump. Researchers can examine stiffness of these joints, specifically joint torsional stiffness, or how easy or hard the joints bend.

Additionally, researchers who study movement can also measure how a dancer’s body makes contact with the ground to determine if certain kinetic factors might be significantly associated with injury. For instance, the difference in the angle at which a dancer’s lower limb makes contact with the ground has been associated with injured and uninjured groups of dancers. If researchers can accurately indicate which angles are associated with injury, they can collaborate with medical professionals and teachers to craft targeted interventions on how a dancer should be properly moving their body.

In the current study, the researchers posited that lower extremity joint torsional stiffness measured when participants made contact with the ground would be altered in dancers with tendinopathy compared to uninjured dancers. They also thought that dancers with tendinopathy would demonstrate a lower limb posture associated with kinetic factors that differed between injured and uninjured dancers.

Using the marker set that the dancers wore, the researchers measured torsional stiffness by examining the rotational forces, or the change of joint movements, over the change of the joint angle over a period of time. This data was gathered as the dancers flexed and extended their lower extremity joints during the saut du chat. Moreover, the team measured the contact angle at which the dancers’ feet took off from.

Dr. Shih and her colleagues found that the dancers with tendinopathy demonstrated less joint torsional stiffness at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP), ankle, and knee joints during the takeoff step of the dance move. To reiterate, research suggests that a lack of joint stiffness is not good because it could lead to soft tissue injury, as it allows for excessive joint motion. Additionally, these injured dancers took longer to reach peak force when pushing off the ground and the peak force was also lower than in the uninjured dancers. Finally, the angle at which dancers first contacted the ground during that take off step was smaller (i.e., their foot was further in front of their pelvis) in participants with FHL tendinopathy compared to those without injury.

How can these findings help dancers and those that provide movement guidance to dancers? Knowing the particular biomechanical changes that precede tendinopathy can inform targeted interventions aimed at improving how dancers move their feet and legs when performing certain moves. For example, teachers can offer cues and guidance on how a dancer should position their pelvis and feet in an effort to prevent injury.

This study by Dr. Shih and her colleagues is the first to demonstrate the differences in movement profiles between dancers with and without FHL tendinopathy and could go a long way to informing interventions that could prolong dancers’ careers.

Dr. Hai-Jung Steffi Shih is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the Neurorehabilitation Research Lab at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her PhD in Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy at the University of Southern California where this research was conducted. Steffi’s research aims are to further understand musculoskeletal pain, movement disorders, and improve intervention strategies using a multidisciplinary approach. Outside of academia, Steffi is an avid traveler who has been to more than 35 countries. She loves to dance, enjoys playing music, and is aspiring to become an excellent dog owner one day. You can email her at [email protected] and connect with her on Twitter @HiSteffiPT.