Thanksgiving is just around the corner. The buttery sweet potato casserole, mashed potatoes, and gravy on the Thanksgiving dinner table are delicious and irresistible for most of us. Though fat from buttery food provides important building blocks for our body, overconsumption of fatty food could lead to weight gain and obesity-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease. To help keep our health in check, we need a better understanding of how fat consumption changes our desire for fatty food. A recent study led by Dr. Mengtong Li in the laboratory of Dr. Charles Zuker at the Zuckerman Mind Brain and Behavior Institute at Columbia University has started to reveal some insights.

Previously the research team discovered how sugar preference was established. They found that among the two ways of processing the intake of sugar, taste and gut pathways, the preference for sugar arises from gut and is independent of taste. In line with this finding, the authors discovered that artificial sweeteners do not create a preference because they activate only taste receptors but not the gut pathway.

Built upon what they have learned from sugar preference, the authors first tested if mice have taste-independent preference for fat as well. They gave the mice a choice between oily water and water with artificial sweetener, and they recorded the number of times that the mice licked either of the water bottles as a measurement for preference. They found that the mice predominantly drank from the bottle with oily water two days after exposure to the two choices. Even when the authors directly delivered fat to the gut through surgery, or in mice that did not have taste receptors, the mice could still develop preference for fat. These observations suggested that mice could develop preference for fat through the gut pathway.

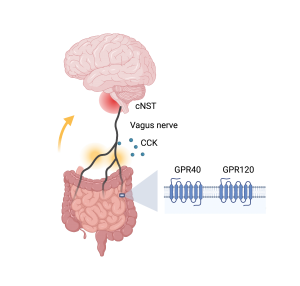

How does the information of fat get transferred to the brain, along the so-called gut-brain axis, and make the mice want fat more than sugar? The authors traced the signals of fat stimuli from gut to brain (Figure 1) through pharmacological and genetic tools. They identified two receptors, G protein-coupled receptors GPR40 and GPR120, that function as fat detectors in the gut. Upon detecting the presence of fat, the gut then releases signaling molecules, including a satiety hormone cholecystokinin, to relay the information to the vagus nerve. Interestingly, while control mice do not have a preference for cherry- versus grape-flavored solutions, the authors were able to create a new preference in experimental mice by artificially activating the subset of vagal neurons that receive cholecystokinin signals from the gut. The vagus nerve travels from gut to brain, and eventually sends the fat signals to the brain region called the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNST) in the brainstem.

Together, the identification of the gut-brain communication might help battle against overindulging in fatty foods. As stress eating could increase the consumption of high calorie foods, it would also be interesting to study how the gut-brain communication is modulated by different emotional states.

Edited by: Maaike Schilperoort, Trang Nguyen, Sam Rossano