China has had a long history of imagining and appropriating Tibet and images from Tibet. However, the focus of this page will be on Chinese interactions with the myth of Shambhala specifically, especially in modern times. An example of this would be in the 1930s, when the ninth Panchen Lama propagated the Kalachakra tantra in China. Due to the prophetic and messianic vision that came with the myth of Shambhala, as well as the fact that the Panchen Lama himself was meant to be reborn as the apocalyptic king of Shambhala, his presence in China “offered the hope of a future rebirth in a place and time which promised to mark the triumph of good over evil” during a time of political instability (Tuttle, 304). Chinese Buddhists and politicians interpreted the traditions and practices that the Panchen lama brought to China in their own way to their own ends. They saw him as a representative of hope from the West, and saw Shambhala as a symbol of Tibet on the whole (both being north of India). They connected the Kalachakra tantra to its Hindu origins, legitimizing it as a valid Buddhist scripture to Chinese Buddhists, and saw the ninth Panchen Lama’s activities as a salvic power to be applied to China. Shambhala, and by political extension Tibet, thus became central in the Chinese imagination of its own salvation (even though the Panchen Lama’s purpose was radically different), bringing about hope that the Panchen Lama would bring Tibet under the Nationalist Chinese state (Tuttle, 326). Although this hope was frustrated by the lama’s death, this is a prominent modern example of Chinese appropriation of the potent imagery and narrative of Shambhala, romanticizing it as an ultimate salve for their troubles and interpreting it within their own context for their own ends.

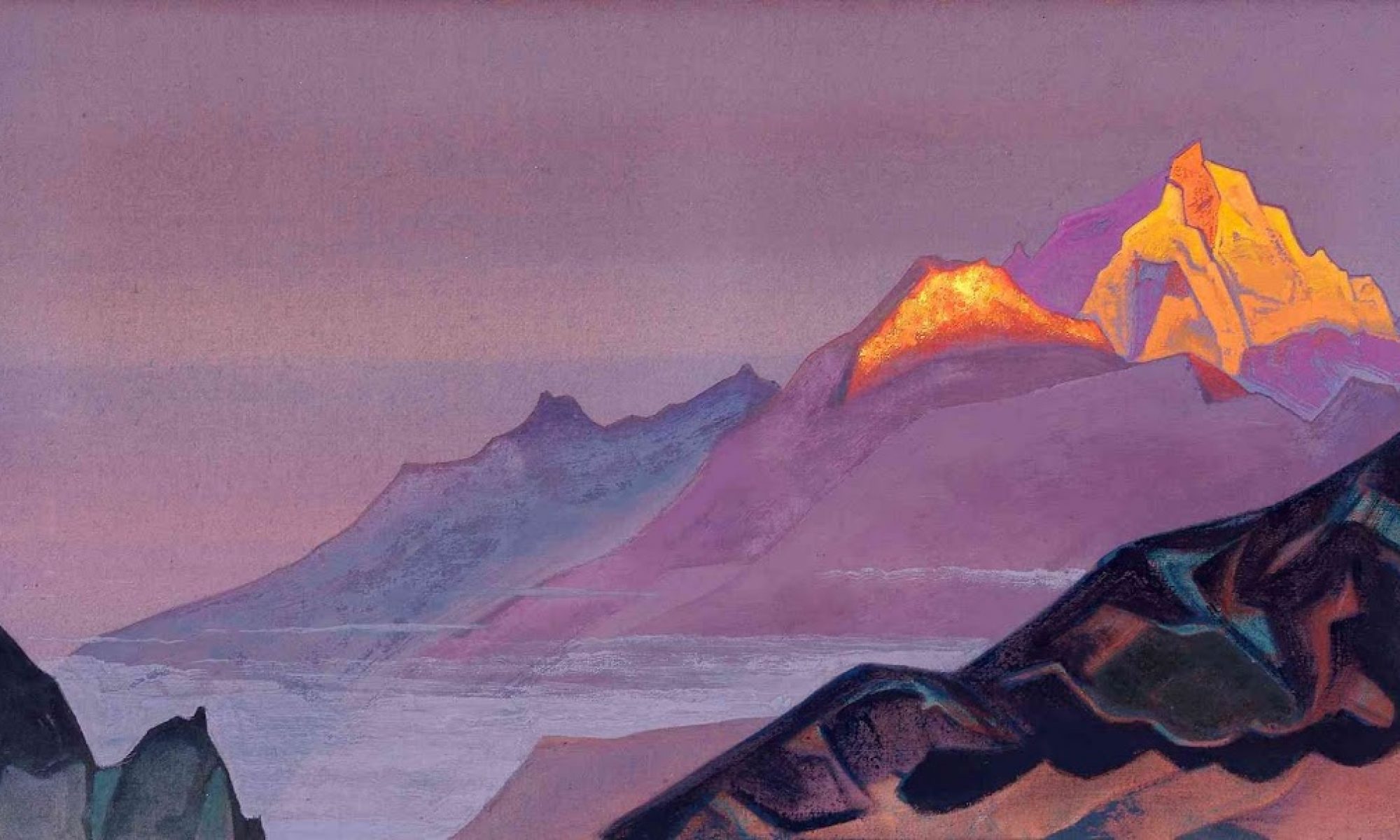

The most manifest and recent example of Chinese appropriation of Shambhala imagery is the county itself in Northwestern Yunnan. In 2001, the PRC renamed Zhongdian County (中甸县) as Shangri-la (香格里拉), explicitly named after the land of Shangri-la from the 1933 James Hilton novel Lost Horizon. This was intentionally crafted to promote tourism in the area, though it erased the original Tibetan name for the area, Gyalthang. This recognition was granted because it “coincides with several goals of the Chinese government, including economically developing interior China, promoting harmony, and portraying its minorities as tranquil and happy” (Llamas and Belk, 257). Shangri-la has therefore become a brand name for tourism, compared to “McDonaldization” (Llamas and Belk, 258). Meanwhile, there is an ongoing process of Orientalization even within the so-called “Orient” (which is meant to include both Tibet and China). Orientalization, coined by Said, refers to the way that the Western bourgeoisie divide the world between East and West, or self and other, and this division engenders “theories, epics, novels, social descriptions, and political accounts concerning the Orient, its people, customs, ‘mind,’ destiny, and so on” (3). China, in its tourism efforts, has similarly used and fed the flames of the stereotypes of Tibet and Shambhala, and not only to international tourists but mostly to domestic tourists. Kolås states that this fantasy is based on the three pillars of sacralization (mysticism, spirituality, and Tibetan Buddhism), ethnitization (ethnic minorities, culture, and harmony), and exoticization (natural and artificial spectacles in this land of lakes, rivers, and snowcapped mountains in the Himalayas). The original meaning of Shambhala, reappropriated into Shangri-la, is therefore mostly lost on both locals and tourists, between whom there exists a great economic divide as well.

The Tibetan poet and activist Woeser has also written an essay criticizing the CCTV six-part documentary “The Third Pole”, which is meant to positively positively depict the Tibetan Plateau as a Shangri-la, as well as the 1963 Chinese film “Serf”. “Serf” was meant to unmask “the most reactionary, darkest, cruelest, and most barbarous” “Old Tibet”, demonizing Tibetan civilization and justifying China’s role as a ‘liberator’ of Tibet. Now, “The Third Pole” is one of many examples of Chinese media which strips the same civilization of its barbarism and instead beautifies it as a land of purity. The documentary depicts the harmony between nature and people through almost forty stories, seeming to celebrate life and beauty. Woeser points out that one cannot solely be focused on the West’s Orientalist tendencies of the East; Chinese media, too, orientalizes Tibet to the point of making it “even more ‘Shangri-la’ than ‘Shangri-la’”. It is now depicted as a “heaven on earth” instead of a primitive, backward place because of Chinese state policies. She deems that the “Shangri-la-isation” of Tibet through “The Third Pole” and the demonization in “Serf” are mere continuations from one another which stem from the same source – Chinese colonialism and control in Tibet.

Overall, in various social, political, and historical contexts, the myth of Shambhala/Shangri-la has been employed by China. When used, it has been romanticized and fetishized often quite far beyond its original context of the Kalachakra tantra and has taken on a life of its own, and is only one out of many images used to depict Tibet (especially the “new” Tibet under China) according to the context. The fact that Shangri-la has become a brand name and that Shangri-la-isation has become a perjorative term speaks to its commodification and thus drips with irony when considering its meaning in the Kalachakra tantra.

The following song called Shangri-la (香格里拉) is sung by Ouyang Feiying (欧阳飞莺), a Chinese singer who became famous in Shanghai in the 1940s, in no small part due to this very song. Written by Cheng Dieyi (陳蝶衣) and composed by Jin Gang (金鋼), it was part of the movie soundtrack for a musical drama (莺飞人间, 1946) that Ouyang Feiying starred in herself as a talented singer who fell in love with a musician. Although more specific details about the conditions of writing the song are difficult to find, its extreme popularity among people at the time (and the fact that it has been canonized by some as one of the most classic Shanghai oldies) speaks of the popular imaginations and the popular sacralization of the sacred space.

Lyrics (translated from Mandarin to English by Wan Yii Lee):

This beautiful Shangri-La, this adorable Shangri-la,

I deeply fell in love with it, I fell in love with it.

Look at these mountains, coves, riversides,

Look at this red wall and green tiles,

As if ornamenting a myth,

Look at these uneven strands of willow.

Look at these flowers blossoming,

Distinctly like a colorfull painting,

Ah, and that warm spring breeze, even more like a light cloth,

We are just under its shroud, singing and laughing,

La la la, ha ha ha, this beautiful Shangri-la,

This adorable Shangri-la, I deeply fell in love with it,

It is my ideal home, Shangri-la.

这美丽的香格里拉 这可爱的香格里拉

我深深地爱上了它 我爱上了它

你看这山隈水涯 你看这红墙绿瓦

仿佛是妆点着神话 你看这柳丝参差

你看这花枝低桠 分明是一幅彩色的画

啊 还有那温暖的春风 更像是一袭轻纱

我们就在它的笼罩下 我们歌唱 我们欢笑

啦啦啦 哈哈哈 这美丽的香格里拉

这可爱的香格里拉 我深深地爱上了它

是我理想的家 香格里拉