It would be amiss for this website not to include a section on how the Occident has represented Shambhala as a sacred space, given that it has entered the popular imagination especially in the 20th Century and that the West has become a large perpetuator of discourse that employs its imagery. From Marco Polo to Galen Rowell, occidental literary paradigms have perpetuated plenty of surreal presentations of Tibet as enigmatic and isolated (Llamas and Belk, 258). The parallels between Tibet’s and Shambhala’s inaccessibility made the two open to conflation, with increased slippage between mentions of Shangri-la and Tibet itself – the myth now takes on national meaning (and it is interesting to note that many of the Western sources about “Shangri-la” that I had encountered during my research were not actually about Shangri-la or Shambhala but simply borrowing the word as a gateway to talking about Tibet). The popularization of the idea of “Shangri-la” came from James Hilton’s 1933 book, Lost Horizon, which was turned into a film by Frank Capra in 1937. The opening scene shows snowcapped mountains, with “Lost Horizon” written in an exotic font mimicking Tibetan script, and after a list of opening credits, the screen shows a mystical book opening up to a page that reads:

“In these days of wars and rumours of wars — haven’t you ever dreamed of a place where there was peace and security, where living was not a struggle but a lasting delight?”

From From Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon” (1937)

From Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon” (1937)

This Western book adaptation of the myth is Orientalism at its finest. Shangri-la is depicted as an idyllic, exotic, mystic place where everything is in harmony and people live young forever, hidden among the Himalayan mountains where only those who are lost can find it. But what makes Shangri-la so invaluable in the book and film is not even the indigenous knowledge of the indigenous people, but that a Belgian Catholic missionary had gathered the pinnacles of European culture (books, art, music) and that a brotherhood of foreigners were protecting them from impending world conflagration. What was precious was not Tibet itself but what it represented, and the treasures that were preserved (Lopez, 5). The imagery of Tibet and of Shangri-la is only useful to the extent that the Occident’s superiority is preserved and unquestioned. Although it would be inappropriate to paint all Occidental people who were interested in Tibet with the same brush stroke, it would be fair to say that a significant amount of early scholarship or discourse about Tibet and Shangri-la was indeed Orientalist.

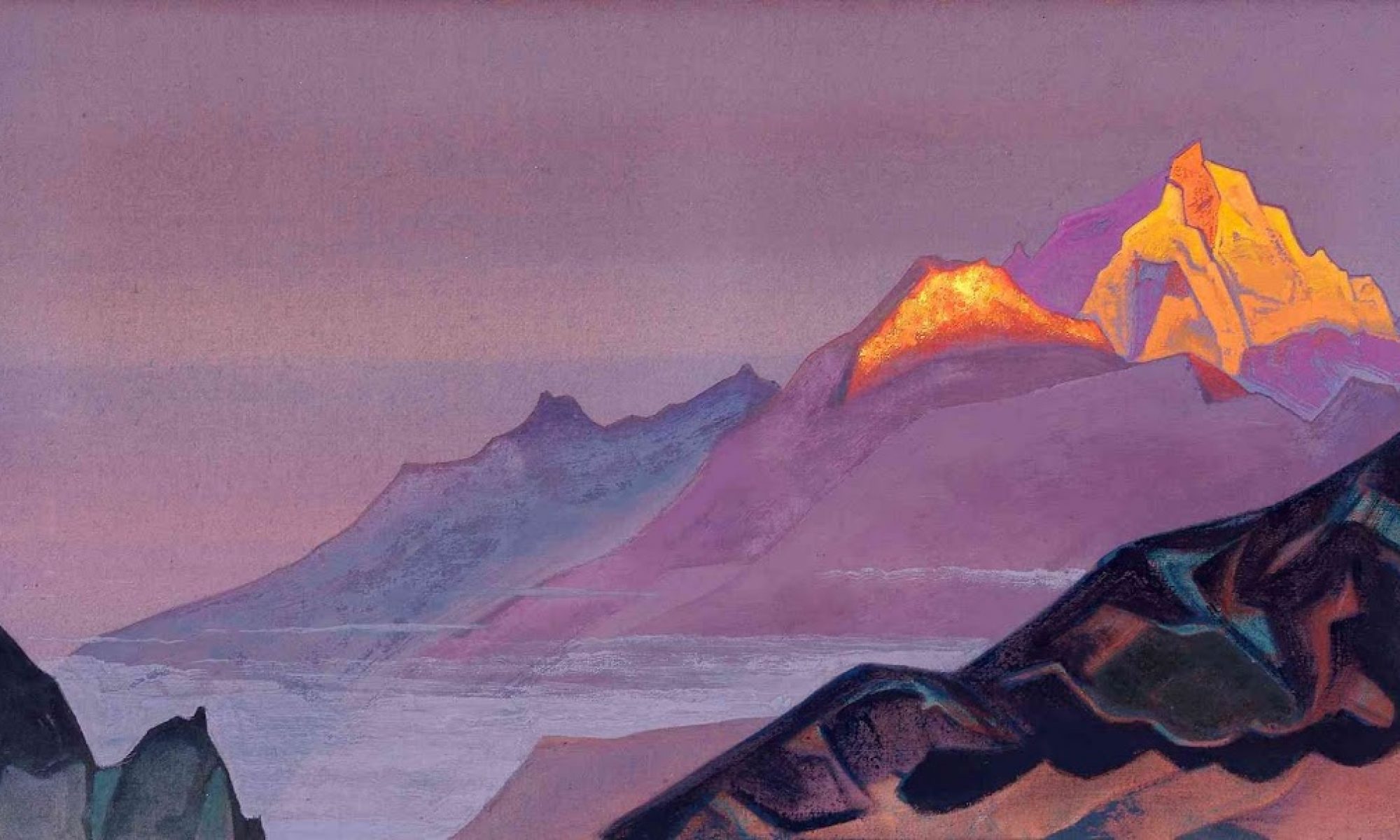

Even long before Hilton’s work, Tibet was already known by European powers with colonial interests in the 19th Century. Because Tibet was always just out of reach of colonization, seen as closed and isolated but never conquered, “many of Europe’s fantasies about India and China, dispelled by colonialism, made their way across the mountains to an idealized Tibet” (Lopez, 6). Lopez points out that many myths were of Tibetan making though, from the guidebooks that they wrote to idyllic hidden valleys (sbas yul) (6). Later, China’s takeover of Tibet was represented as “godless Communists overrunning overrunning a peaceful land devoted only to ethereal pursuits” (Lopez, 7). Orientalism was split between a benign and englightened Orient, the latter of which would be hailed as a salve for the Western spirit. One such group that believed this was the Theosophists, who heavily influenced Nicholas Roerich. Roerich’s book Shambhala (1930) showed that he even looked forward to the apocalyptic reckoning of the world, and a mysterious expedition to Inner Mongolia in 1934-35 that was unaccounted for was also rumoured to have been made in search of Shambhala (Boyd, 258). This interest even inspired him to create the Roerich Pact and Banner of Peace, a treaty about respecting and preserving cultural/scientific treasures with the vision of enlightenment in mind. This connection can be seen at a speech given at the Third International Roerich Peace Banner Convention in 1933: “The East has said that when the Banner of Shambhala would encircle the world, verily the New Dawn would follow. Borrowing this Legend of Asia, let us determine that the Banner of Peace shall encircle the world, carrying its word of Light, and presaging a New Morning of human brotherhood” (Bernbaum, 21). This strikingly reminds one of the way the Chinese used the messianic image of Shambhala for their own political agendas.

Even currently, popular books, songs (see below), media, and franchises (think of the luxury hotel chain) continue to employ the imagery of Shangri-la. There is the continuing sense that it is an eternaly pure mystery, but also that there is a need to seek out the “real” and pure Shangri-la, seen even in book titles such as “Shambhala: The Fascinating Truth behind the Myth of Shangri-la”, published by Victoria LePage in 2014 (the book is a continued attempt to argue that Shambhala is “real” and “may be becoming more so as human beings as a species learn increasingly to perceive dimensions of reality that have been concealed for millennia”). Although possibilities of reading into Western representations of Shambhala are endless and there is much more to be said than cannot be covered in this website, what is worth taking away is also that Tibetans and Tibetan myths were not simply passively objectified – although many Western representations of Shangri-la are out of the hands of Tibetans, it is important to acknowledge that they were also part of the process of myth-making in many ways. This section delves further into this last point.

Lyrics:

Your kisses take me to Shangri-La

Each kiss is magic that makes my little world a Shangri-La

A land of bluebirds and fountains and nothing to do

But cling to an angel that looks like you

And when you hold me, how warm you are

Be mine, my darling, and spend your life with me in Shangri-La

For anywhere you are is Shangri-La

Your kisses take me to Shangri-La

Each kiss is magic that makes my little world a Shangri-La

A land of bluebirds and fountains and nothing to do

But cling to an angel that looks like you

And when you hold me, how warm you are

Be mine, my darling, and spend your life with me in Shangri-La

For anywhere you are is Shangri-La