Following is a post by Steve Mooney on a recently published paper. Dr. Mooney is an alum of the Doctoral Program in Epidemiology and the Social Epi Cluster.

We’ve done a lot with Street View at the Built Environment and Health Research Group, and we think the CANVAS application we developed to help teams do reliable and efficient virtual audits works pretty well. But we never really knew what we might be missing by not being on the street in person.

Fortunately, we stumbled across an opportunity to investigate what we might be missing. It happens that our friends at the Detroit Neighborhood Health Study (DNHS) had conducted an in-person systematic audit of Detroit streets only one year prior to when Google captured the imagery that we’d audited on Street View, and the DNHS team had constructed a physical disorder measure from their work.

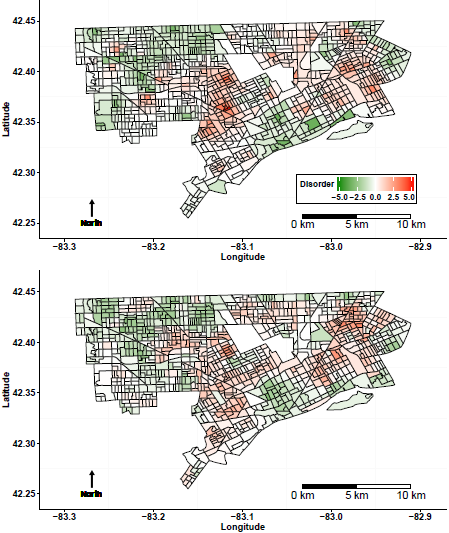

So we took a look at how their measure aligned with ours, and together, we and the DNHS team recently wrote a paper on what we found. Spolier alert: both methods showed pretty similar spatial patterns of disorder — the final measures were significantly positively correlated at census block centroids (r=0.52), identified the same general regions as highly disordered (see attached image) and displayed comparable leave-one-out cross-validation accuracy.

So we took a look at how their measure aligned with ours, and together, we and the DNHS team recently wrote a paper on what we found. Spolier alert: both methods showed pretty similar spatial patterns of disorder — the final measures were significantly positively correlated at census block centroids (r=0.52), identified the same general regions as highly disordered (see attached image) and displayed comparable leave-one-out cross-validation accuracy.

But the two methods didn’t take the same amount of auditor time – the virtual audit required about 3% of the time of the in-person audit, largely because the virtual audit was able to take a more diffuse sample of the streets because travel time between segments was not a factor in developing an audit sample.

There were a number of other differences between the audit designs, including that the CANVAS audit included more disorder indicators and the DNHS audit aggregated street-level measures to create neighborhood area measures before interpolating. So it wasn’t a completely apples-to-apples comparison and the 97% of auditor time saved might not apply for other audit contexts. Nonetheless, virtual audits do appear to permit comparable validity with more diffuse samples.

Ultimately, we concluded that the virtual audit-based physical disorder measure could substitute for the in-person one with little to no loss of precision. Jackelyn Hwang wrote a thoughtful commentary on our paper and on technological innovation in neighborhood research more generally, and we responded to her thoughts.