Location, location, location. Anyone who has been in the real estate market knows that location is one of the most important factors in determining property value. But, a large body of evidence indicates that property value is not the only thing determined by location. Where a person lives has a large influence on that person’s overall health and well-being. In fact, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has linked residential zip code to quality and length of life, demonstrating that just a few miles difference in place of birth can lead to large health disparities and as much as a 25 year difference in life expectancy.

The reasons for this gap are, of course, multifactorial. Epidemiologists and sociologists have made incredible strides in demonstrating how the community in which you live affects your health through social and economic conditions. There are several explanatory mechanisms for this phenomenon, including access to healthcare, prevalence of crime, proximity to physical activity resources, and availability of fresh produce. Another important neighborhood contextual factor is environmental pollution.

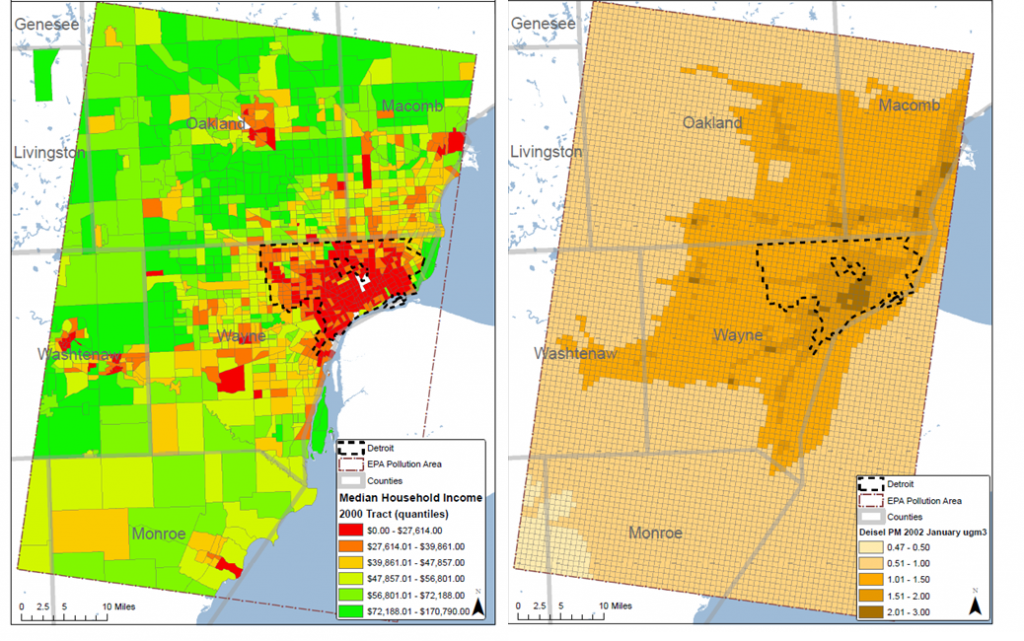

Median House Hold Income (2000) and winter Diesel Particulate Matter levels (EPA – 2002) in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. Maps by Dan Sheehan

That the burden of environmental pollution may be disproportionately felt in certain neighborhoods, particularly low-income or minority neighborhoods, is not a new idea. Environmental justice, defined by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies, gained widespread attention in the early 1980s. At that time, community leaders pointed to the greater burden of environmental hazards on residents in low-income and minority communities compared to the general population. Following the public demonstration by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People against dumping of contaminated soil near a low-income, predominantly minority community, several investigations were conducted on environmental inequity. The results of this injustice were documented in multiple landmark reports. Since that time, community leaders, activists, environmental researchers, and the federal government have worked to address these inequities through research, empowerment, and policy changes.

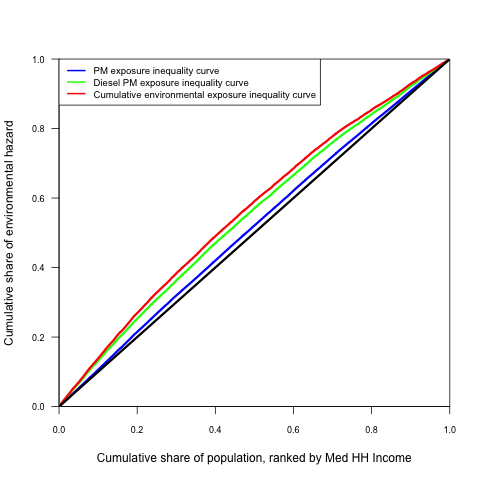

With data on estimated air pollution levels from the US EPA’s Detroit Multipollutant Pilot Project and the year 2000 US Census, we looked at how environmental injustice plays out across 1,269 census tracts in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. Using a method described by Su and colleagues, we present a visual summary of the relative environmental inequality for exposure to airborne Particulate Matter and Diesel Particulate Matter by Census tract across the entire socioeconomic distribution. The cumulative proportion of the population, ordered by area-based percentage of socioeconomic distribution, from the most disadvantaged to the most advantaged, is plotted against the cumulative share of the environmental hazard, for each census tract. If each population group had the same share of cumulative impact of environmental hazard, the curve would coincide with equality (black line). The curves above the line of equality indicate that neighborhoods with lower household income in the Detroit Metropolitan Area have a disproportionately higher share of environmental burden for the air pollutants examined.

Inequality in exposure to Particulate Matter and Diesel Particulate Matter in the Detroit Metropolitan Area by Census tract Median House Hold Income. The curved lines above the black line indicate that lower income tracts experience higher burdens of air pollution exposure.

Community advocates have long argued that racial and ethnic minority neighborhoods and lower income neighborhoods are burdened by multiple environmental and socioeconomic stressors, contributing to a “double jeopardy”. However, all too often, as researchers, we can be singularly focused on our particularly area of interest. For some, neighborhood environment means parks and recreation areas, for others it means socioeconomic context, and yet others think of environmental pollutants. This discipline-specific focus can prevent the realization of all the available opportunities to improve public health. As in the case of Detroit, environmental and social determinants of health are frequently spatially clustered. They can also act synergistically to have a greater impact on health outcomes than if one was exposed to each in isolation. Similarly, singular policy changes can have a wide range of implications regarding social, environmental, and physical health. For example, urban “greening” has been linked to improved physical and mental health. Green space can also mitigate the urban heat island and improve air quality.

A person’s neighborhood includes a wide array of contextual factors that may exhibit complicated interrelationships to affect population health. The time is ripe for social and environmental epidemiologists to work together to take an integrated approach to improving public health.

– Jaime Madrigano is an Associate Policy Researcher at the RAND Corporation and was previously a Postdoctoral Fellow at Columbia University and was a member of the Built Environment and Health Research Group. Her web site is http://jmadrigano.com