The name of this website (“The Great Melody of Illusion, the False Account of a Dream”, or rMi lam rdzun bshad sgyu ma’i sgra dbyangs chen mo) was the name of the document that contained the earliest datable Tibetan itinerary to Shambhala by Man lung Guru (b. 1239). This itinerary, although written in an extremely matter-of-fact manner that is based in materiality, also has a name that implies the author’s view about the illusory nature of material reality. Thus, it is a name that alludes to both the material and the imaginary, landscapes and dreamscapes, the concrete and the illusory – sites of contradiction that are central to the notion of Shambhala, or Shangri-la.

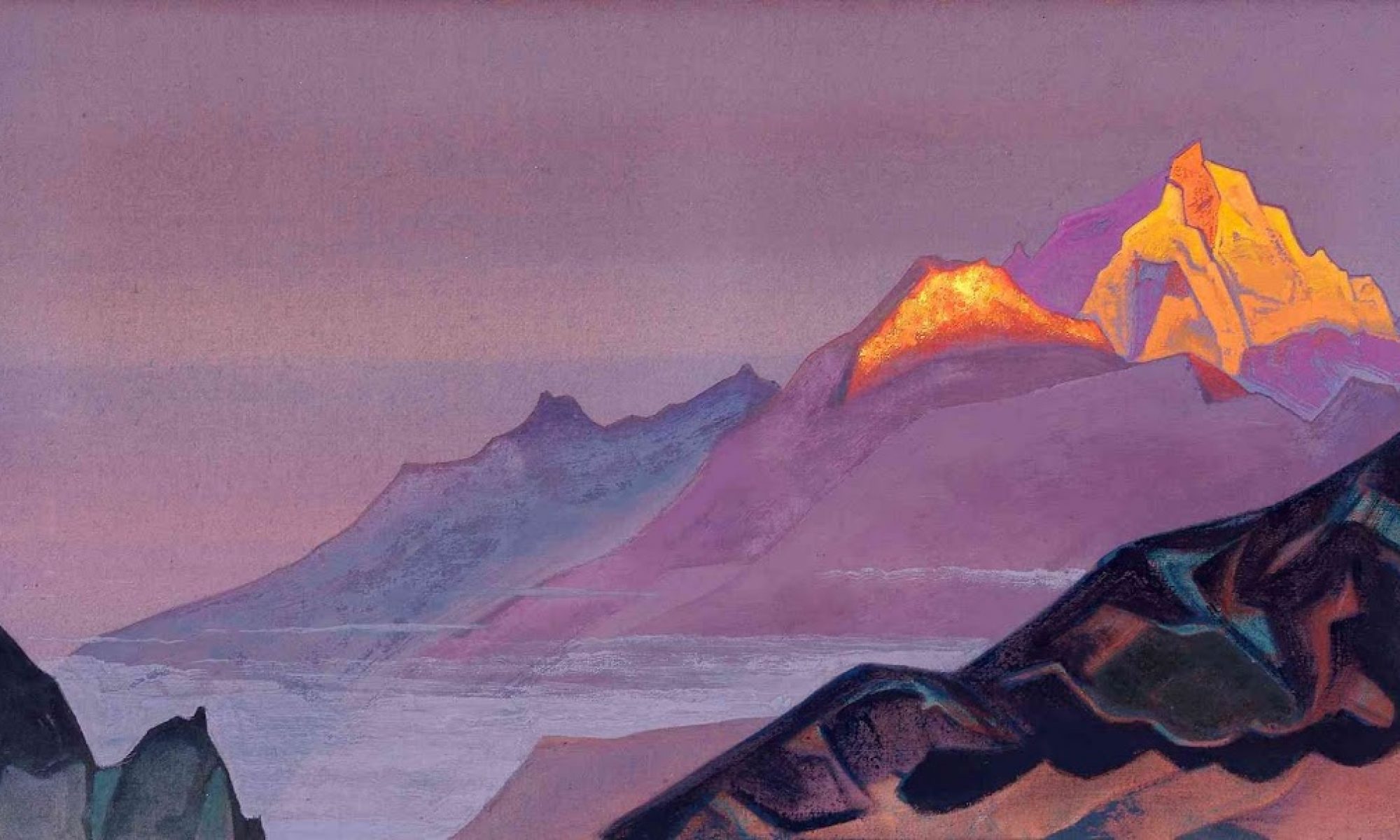

Meanwhile, the painting in the background is entitled Path to Shambhala, painted by Nicholas Roerich in 1933. Roerich was a Russian artist, visionary, and mystic who published a book in 1930 titled Shambhala, and who made an expedition to Inner Mongolia in 1934-35 reportedly in search of the mythical kingdom. The painting depicts mountains cast in layers of deep purple, with the morning sun just beginning to strike the mountaintops while their bodies remain shrouded in darkness and mystery. These mountains could be any mountains, not seeming to possess any particular qualities that lend them specific identification; and at the same time, in the title of the painting, Roerich is boldly staking a claim that these are mountains that are part of the elusive kingdom of Shambhala, or at least are part of the journey there.

The superimposition of the website title, derived from the earliest known Tibetan itinerary to Shambhala, upon the 20th Century painting of a foreign artist, who was known to be influenced by the Theosophists and Orientalists, speaks of the ambition of this website, spanning both time and space. Both (as different representations of Shambhala) also tread the line between the material and the illusory. Shambhala is a sacred space that, as far as we know, seems to mostly inhabit the realm of discourse, media, and representation, which is why (without access to Shambhala itself) an exploration into such a realm of representation is warranted.

For most discussions on sacred space, an element of materiality is assumed. Kim Knott’s work, which focuses on a spatial analysis of religion, discusses the sociology and theorization of space but is still premised on the assumption of material space that one can interact with, seen in her application of Lefebre’s Spatial Triad and her analysis of the Left Hand. However, in the case of Shambhala, there hasn’t been any consensus on where it might be in the material world, or whether it even exists. Thus, there is room for a project documenting the sacralization of this non-material sacred space, around which traditional practices such as physical ritual, circumambulation, etc. cannot apply in orthodox ways. The aim of this project is not to seek out the “real” Shambhala (as has been the aim of many other works), nor is it to disprove its existence entirely. It also does not treat Shambhala/Shangri-la as a stand-in for Tibet on the whole (as much scholarship does). Instead, this website humbly hopes to lay out various representations of Shambhala, be it via text, image, or even songs. Given its limited access to English-only sources (and some Mandarin sources) and lack of access to primary sources in Tibetan, it lays no claim at all to exhausting all representations of the popular image – still, it endeavors to document certain representations that were particularly interesting or noteworthy in understanding Shambhala as a sacred space to many different people. In the section on Chinese representations, it also offers self-translated works (Mandarin-English) to offer examples of the Chinese imagination of Shangri-La. It is particularly fitting for it to be represented on this website, an online space which, like physical space, defies two-dimensional linearity and promotes relationality but still, like Shambhala, is experienced non-materially.

Although one may toggle around and visit any section of the website at any time (such is the fun of an online space, being non-linear), I would suggest starting with the “Kalachakra” section for those who are unfamiliar with the historical context and origins of notions of Shambhala, before moving onto “Foreign Imaginations” and “Modern Tibet”.