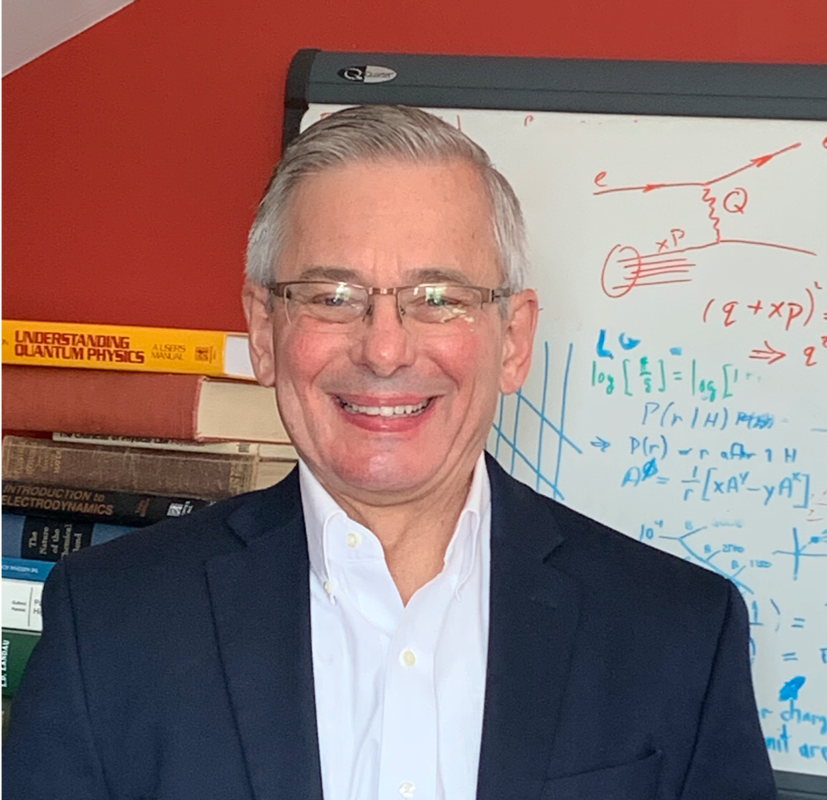

To the extent I have made progress in physics, it has been through the guidance of essential mentors at each point of my career. Along the way, I’ve made many friends, too many to list, but at least one of them deserves special mention. And at some point, as in the case of my “Dai-Sensei” Shoji Nagamiya, mentors and friends become one and the same.

Tom Tombrello:

I began working for Tom in m y sophomore year at Caltech. Tom was leading the way in the Division of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy (PMA) in involving undergraduates in research. This is now routine, but it was viewed as an odd experiment some 40+ years ago. Tom later went on to lead Caltech’s PMA for many years, and played a key role in guiding Caltech’s involvement in LIGO. This is but one of Tom’s incredible achievements in that role; you can read a (nearly) complete account of his time at Caltech in his extended interview as part of the Caltech Oral History project. There is a separate interview detailing some of the turbulence in the early years of the LIGO project.

y sophomore year at Caltech. Tom was leading the way in the Division of Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy (PMA) in involving undergraduates in research. This is now routine, but it was viewed as an odd experiment some 40+ years ago. Tom later went on to lead Caltech’s PMA for many years, and played a key role in guiding Caltech’s involvement in LIGO. This is but one of Tom’s incredible achievements in that role; you can read a (nearly) complete account of his time at Caltech in his extended interview as part of the Caltech Oral History project. There is a separate interview detailing some of the turbulence in the early years of the LIGO project.

Tom assigned me a rather challenging project of calculating the normal modes of linear accelerator resonator cavity loaded with a spiral support tube. To say this was challenging for a sophomore physics student is a bit of a challenge. I worked on it for a few weeks, and after an all-nighter went to see Tom. I recall him saying something like “well, I played around with this a bit last night myself”, and then pulled out a much more complete result than mine. To say I was humbled would be an understatement, but I was also inspired and went on to use some obscure conformal transformation method to compute the resistive currents in the structure.

Perhaps the most important thing Tom did in my career was to refuse to write a letter of recommendation for graduate school at the University of Hawaii. He told me “I know the only reason you want to apply there is to go to the beach, so don’t waste my time.” But he did write for me for UC-Berkeley, which turned out to be the only school I applied to. One of the very few times I got away with doing something so stupid…

Ken Crowe:

I was somewhat directionless after my second year of graduate school at UC-Berkeley. Somehow I became intrigued by Weinberg’s papers on soft-pion theorems, and was curious about experimental implications. I went to talk to Ken, who immediately took me on as a student, which was important because I was completely broke. I don’t think thought for one second that my ideas on soft pions were of any experimental significance, but he did assign me to work on various things pionic in the realm of what today is called medium energy nuclear physics. I recall my first trip to Los Alamos to work on a low-energy beam-line at LAMPF, and how much I enjoyed both the setting and seeing beam-line optics in action.

I was somewhat directionless after my second year of graduate school at UC-Berkeley. Somehow I became intrigued by Weinberg’s papers on soft-pion theorems, and was curious about experimental implications. I went to talk to Ken, who immediately took me on as a student, which was important because I was completely broke. I don’t think thought for one second that my ideas on soft pions were of any experimental significance, but he did assign me to work on various things pionic in the realm of what today is called medium energy nuclear physics. I recall my first trip to Los Alamos to work on a low-energy beam-line at LAMPF, and how much I enjoyed both the setting and seeing beam-line optics in action.

Ken was tough and demanding – this is the theme in the fond remembrances of Ken here. If after a few years you did not learn how to respond in kind, you were in trouble. So I learned. But much more importantly, Ken was supportive both in “small” ways (I vividly recall him reading the riot act to a member of the computer support staff at LBL who had managed to erase a month of tape processing from a portable disk, and getting that tech’s superviser to force him to supply his month of effort to re-do the processing), and truly large ways. In particular, when I went to Ken to tell him about an interesting talk I had just heard from a young postdoc named Miklos Gyulassy (see below), Ken encouraged me to design an experiment to explore the topic, which was an entirely new direction of Ken’s experimental program. It’s a rare Ph.D. supervisor indeed that would take on a major new program based on the report from a young graduate student with a funny name on a talk from a young postdoc with a funny name about an obscure technique from another field. But Ken was open that, and that experiment became my thesis topic. I am forever grateful to Ken for his encouragement. See my remarks here for additional details.

Miklos Gyulassy:

Miklos was a young postdoc in the Nuclear Science Division at LBL when he gave a seminar circa 1977-78 on the application of identical boson interferometry in nuclear collisions. I had read about the optical counterpart, the Hanbury Brown Twiss (HBT) effect in Gordon Baym’s Quantum Mechanics textbook when I was a undergraduate, and the idea of doing this “real” particles, in this case pions coming from nuclear collision was very interesting to me. Particularly intriguing was the idea of pion “lasers” where the coherence of the pion field would destroy the HBT effect.

Miklos was a young postdoc in the Nuclear Science Division at LBL when he gave a seminar circa 1977-78 on the application of identical boson interferometry in nuclear collisions. I had read about the optical counterpart, the Hanbury Brown Twiss (HBT) effect in Gordon Baym’s Quantum Mechanics textbook when I was a undergraduate, and the idea of doing this “real” particles, in this case pions coming from nuclear collision was very interesting to me. Particularly intriguing was the idea of pion “lasers” where the coherence of the pion field would destroy the HBT effect.

When it came time to design an actual experiment, I learned from Miklos how to calculate pair rates, average over impact parameters, etc. This is all standard now, but no so much in those early days of heavy ion collisions.

Miklos is now a colleague and a friend, but his support and help in my student days remains very much appreciated.

Peter Truöl:

Peter Truöl was a Swiss physicist with a position at Swiss Institute for Nuclear Research (now incorporated into the Paul Scherrer Institute) who regularly visited Ken Crowe’s group in Berkeley. When it came time to analyze the data from my thesis experiment, Peter was an invaluable resource. He was meticulous in seeking to work through every detail of the analysis chain and understand every possible anomaly. This same care extended to his notes, which is where I picked up my lifetime habit of using copious amounts of White-Out in my both my notebooks and my homework solutions (perhaps now a thing of the past as I am now using GoodNotes on my iPad Pro for such things).

Peter Truöl was a Swiss physicist with a position at Swiss Institute for Nuclear Research (now incorporated into the Paul Scherrer Institute) who regularly visited Ken Crowe’s group in Berkeley. When it came time to analyze the data from my thesis experiment, Peter was an invaluable resource. He was meticulous in seeking to work through every detail of the analysis chain and understand every possible anomaly. This same care extended to his notes, which is where I picked up my lifetime habit of using copious amounts of White-Out in my both my notebooks and my homework solutions (perhaps now a thing of the past as I am now using GoodNotes on my iPad Pro for such things).

Sherman Frankel:

As a graduate student, I gave a talk at a 1981 workshop at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. At the end of the session, a dapper gentleman with a remarkable resemblance to the actor Jason Robards approached me and asked if I would like to take a post-doctoral position with him at the University of the Pennsylvania, to work with him on a experiment at CERN. This was like a dream come true, because I had been reading a great deal about CERN and its various physics programs, which seemed so sophisticated compared to what we were doing at the Bevalac. It took me over a year from that offer to finish up my thesis, but Sherman waited (not so) patiently.

As a graduate student, I gave a talk at a 1981 workshop at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. At the end of the session, a dapper gentleman with a remarkable resemblance to the actor Jason Robards approached me and asked if I would like to take a post-doctoral position with him at the University of the Pennsylvania, to work with him on a experiment at CERN. This was like a dream come true, because I had been reading a great deal about CERN and its various physics programs, which seemed so sophisticated compared to what we were doing at the Bevalac. It took me over a year from that offer to finish up my thesis, but Sherman waited (not so) patiently.

Sherman was remarkably creative, witty, and both cultured and profane. He thought deeply about physics, while always working to increase his understanding through the development of (wherever possible) simple models. He also constantly advised me on how to take the next steps in my career, often telling me “Bill, don’t hide your light under a bushel basket”. This is why I was so gobsmacked to read in Joe Polchinski’s autobiographical memoir that he had received exactly the same admonition from Howard Georgi.

Shoji Nagamiya:

I had met Shoji when I was a graduate student. My ratty looking thesis experiment was in the same experimental “cave” as Shoji’s elegant spectrometer, designed with the same care and attention to detail as a Bento box. Shoji was already a thought leader in the new field of relativistic heavy ion physics, distinguished by his insistence on performing precision measurements.

I had met Shoji when I was a graduate student. My ratty looking thesis experiment was in the same experimental “cave” as Shoji’s elegant spectrometer, designed with the same care and attention to detail as a Bento box. Shoji was already a thought leader in the new field of relativistic heavy ion physics, distinguished by his insistence on performing precision measurements.

By the time I received my Ph.D. in 1982, I had grown disillusioned with the field, feeling that the rigor of Shoji’s approach was losing out to the vigor of the “crash and splash” school of thought. This may not have been a fair assessment, but it was consistent with both Ken Crowe’s and Sherman Frankel’s viewpoints as well, and in fact I viewed Sherman’s offer to work at CERN as a way to transition to high energy physics, which led to a brief foray on the very early days of the D0 experiment when I was at Penn. For various reasons this did not work out, which is I why I was thrilled when Shoji called me and asked me to apply for an assistant professor position at Columbia, where he had been hired to lead a new program in heavy ion physics at Brookhaven National Lab. That did work out!

I could and perhaps should write a book about all that I learned from Shoji. Here I’ll simply note his good humor, patience, perseverance and endless dedication to the task at hand. All these traits, combined with his excellent physics insight and superb interpersonal skills, make him a unique figure in our field. I was very fortunate to have him as a mentor, and now as a colleague and friend.

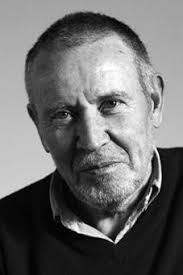

Joe Polchinski:

Joe was my oldest friend in physics (oldest in the sense of having known him longer than any other physics friend or colleague). We met each other in our first week in our first year at Caltech. Joe was initially somewhat more interested in mathematics than physics, but it was immediately clear that 10% of Joe thinking about physics was much more impressive than 100% of Bill. When he quickly turned his full focus to physics, he was kind enough to let me tag along as best I could. We spent endless ours talking about physics, arguing about physics, and doing physics, as we were both working for Tom Tombrello.

Joe was my oldest friend in physics (oldest in the sense of having known him longer than any other physics friend or colleague). We met each other in our first week in our first year at Caltech. Joe was initially somewhat more interested in mathematics than physics, but it was immediately clear that 10% of Joe thinking about physics was much more impressive than 100% of Bill. When he quickly turned his full focus to physics, he was kind enough to let me tag along as best I could. We spent endless ours talking about physics, arguing about physics, and doing physics, as we were both working for Tom Tombrello.

On Spring Break of our junior year, Joe and I took our bike on the train from Los Angeles to Oakland to visit UC-Berkeley before biking some 800 km back to Pasadena. We were given a warm reception and tour of Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory by then Physics Chair Geoffrey Chew. It was only years later I realized how unusual this was, and I don’t think it’s because Prof. Chew thought I would be a major catch for the Berkeley Physics Department… In any event, this led to our parallel paths as graduate students at Berkeley, Joe of course in theoretical physics and me in experimental physics.

Joe’s passing in February of 2018 was an incredible loss of an incredible physicist and a dear friend. True luminaries have written an elegant tribute to Joe’s impact on physics. Other tributes abound, such as this one. Here is mine, repurposed slightly from another site.