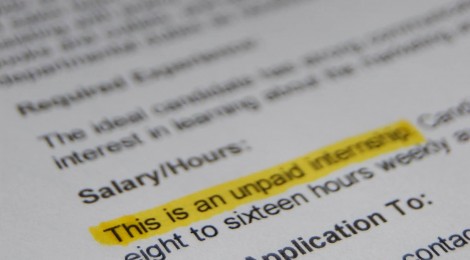

Are Unpaid Internships Legal?

Americans participate in 1.5 million internships per year, half of which are unpaid [1]. Although unpaid internships lack formal compensation, young students are often won over by promises of work experience and prospects for career advancement. In recent years, the legality of unpaid internships has been put under scrutiny. For both the non-profit and public sectors, the Department of Labor (DOL) considers unpaid internships to be “generally permissible.”[2] For the private sector, however, the government operates with greater stringency.

In 2010, the DOL released a factsheet in response to the growing popularity of unpaid internships. The agency set six stipulations, derived from Supreme Court case Walling v. Portland (1947), that must be met by for-profit businesses in order to bypass the wage and overtime requirements of the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). According to the brief, an unpaid internship must resemble training in an “educational environment.”[3] Moreover, employers must not obtain any “immediate advantage” from the intern’s activities, nor should the hiring of interns “displace regular employees.”[4]

A year after the DOL’s guidelines were established, interns who had worked on the film “Black Swan” sued Fox Searchlight Pictures, arguing in a New York federal district court that that they should have received compensation. Because the interns performed tasks that would otherwise have been done by paid employees, Fox’s lawyers did not dispute that the company attained an “immediate advantage” from their work.[5] They contended, however, that the DOL’s six-factor test was “not the applicable standard” and proposed the “primary beneficiary test” as a better alternative. [6] According to this test, if an intern is the primary beneficiary of the relationship, then he does not have to be paid.

In June 2013, the judge deemed the DOL’s criteria “entitled to deference” and ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor.[7] The court determined that the interns’ labor warranted back pay and granted them class action certification.[8] The Glatt et al. v. Fox Searchlight decision was the first ever to affirm that interns are employees under the FLSA.[9] The ruling was especially surprising given that, in a similar case that had been adjudicated a month earlier, another federal district judge in New York reached a different conclusion. In that court case, Wang v. Hearst, the judge saw the DOL’s criteria as a loose “framework for… analysis” rather than a strict “one-dimensional test.”[10] As a result, the plaintiffs in Wang v. Hearst were denied partial summary judgment and the pursuit of collective litigation.

In light of the divergent outcomes, arguments for both cases were heard in tandem by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In its opinion on July 2, 2015, the three-judge panel refused to defer to the DOL’s “rigid” six-factor test, finding that it was neither within the agency’s responsibility nor its expertise to interpret judicial decisions.[11] Instead, the judges embraced the defendants’ “primary beneficiary test,” designating seven criteria that measure the extent to which an internship complements an intern’s education.[12] They stipulated, however, that the circumstances of each case should be evaluated “beyond the specified factors.”[13]

Because it felt that the classification of an intern’s employment status was a “highly individualized” matter, the Second Circuit overturned the lower court’s approval of class certification in Glatt et al. v. Fox Searchlight and affirmed the denial in Wang v. Hearst.”[14] The Court vacated both summary judgment decisions and remanded the cases for de novo proceedings, during which the plaintiffs will have to prove that they qualify as employees under the newly proffered test.

As a result of the ruling, employers have secured a more relaxed set of standards—one that has prompted concern amongst former, current, and prospective interns. Rachel Bien, who represents Glatt et al. and Wang, worries that the Court’s criteria are removed from the terms of the FLSA and may promote the exploitation of free labor. Even before the court’s ruling, many interns who felt they deserved pay feared filing complaints with the DOL, let alone filing lawsuits against employers.[15] Interns like Glatt et al. and Wang, who have taken their cases through trial, are few and far between. The Second Circuit’s recent decision now further diminishes the odds of successful legal action against employers. Regardless of how the plaintiffs in the aforementioned cases fare in subsequent proceedings, the Court’s interpretation of each intern’s case as a personalized inquiry hinders potential for large class actions.

In contrast, Fox has publicly stated that increased protection of its internship program makes students “the real winners.”[16] Ms. Bien has also noted how the court’s decision may be valuable to interns. Namely, the Second Circuit has defined a clearer standard, under which she believes “many of the most abusive internships… are plainly illegal.”[17]

Eric Glatt, for instance, is likely to prevail under the new test. Since he was not enrolled in an academic institution at the time of his internship, it will be challenging for Fox to prove that his work supplemented an academic course of study.[18]

Ultimately, despite the attention surrounding the latest ruling, it remains to be seen whether other courts will acquiesce to the Second Circuit’s seven-factor test. In New York, where there is a generous six-year statute of limitations for wage claims, the Department of Labor maintains a rigorous eleven-factor test of its own to regulate employers under state laws. Therefore, state courts that are sympathetic to the interns’ cause may honor these guidelines over those of the federal appeals court. The Second Circuit’s ruling was a setback to many who had celebrated over the Glatt decision in 2013, but all parties must consider the possibility of jurisdictional disagreements. For employers, this may constitute grounds to increase contractual defenses from lawsuits; for interns, it offers the hope of achieving plaintiff-friendly decisions.

[1] Davidson, Paul. Fewer unpaid internships to be offered. USA Today (2012), online at http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/story/2012-03-07/summer-internships-paid-unpaid/53404886/1 (visited July 20, 2015).

[2]Fact Sheet #71: Internship Programs Under The Fair Labor Standards Act. United States Department of Labor (2010), online at http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs71.htm (visited July 19, 2014).

[3] id

[4] id

[5] Glatt et al. v. Fox Searchlight Pictures Inc., No. 11-cv-6784, 2013 WL 2495140 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

[6] id

[7] id

[8] id

[9] Casuga, Jay-Anne B. Judge Rules Fox Searchlight Interns Are FLSA Employees, Certifies Class Action. The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (2013), online at http://www.bna.com/judge-rules-fox-n17179874627/ (visited July 21, 2015).

[10] Wang v. The Hearst Corporation, No. 12-cv-792, 2013 WL 3326650 (S.D.N.Y 2013).

[11] Glatt et al. v. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Inc. No. 13-4478-cv (2d Cir. 2015).

[12] id

[13] id

[14] id; Wang v. The Hearst Corporation, No. 13-4480-cv (2d Cir. 2015).

[15] Greenhouse, Steven. The Unpaid Intern, Legal or Not. The New York Times (2010), online at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/03/business/03intern.html (visited July 21, 2015).

[16] Sheiber, Noam. Employers Have Greater Leeway on Unpaid Internships, Court Rules. New York Times (2015), online at http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/03/business/unpaid-internships-allowed-if-they-serve-educational-purpose-court-rules.html (visited July 21, 2015).

[17] Wiessner, Daniel. Unpaid internships legal when they boost interns’ learning, U.S. court rules. Reuters (2015), online at http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/07/02/employment-internships-idUSL1N0ZI12720150702 (visited July 23, 2015).

[18] Sheiber, Noam. Employers Have Greater Leeway on Unpaid Internships, Court Rules. The New York Times (2015), online at http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/03/business/unpaid-internships-allowed-if-they-serve-educational-purpose-court-rules.html (visited July 21, 2015).