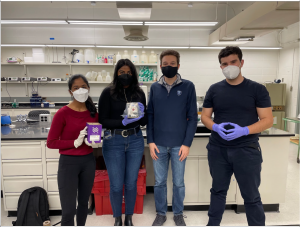

The Columbia SPOCS Team Co-Leads, Kalpana Ganeshan and Swati Ravi, Columbia SPOCS Outreach Lead Theodore Nelson, and Columbia SPOCS Mechanical Engineering Lead

Alfonso Ussia hold up the spaceflight-flown Characterizing Antibiotic Resistance in Microgravity Environments (CARMEn ) payload before unpacking at Columbia University.

SPOCS Biology. Advisor Bryan Wang is not shown. Photo Credit: Theo Nelson.

At the beginning of my Columbia College journey, I, an eager and excited freshman, attended the virtual activities fair, filled with zoom links which would form the entirety of my university environment for what felt like an indeterminate future. In some rooms I found upperclassmen wistfully recounting the glories of olden days; in other rooms spirited organizers promised an endless parade of zoom events. In the Columbia Space Initiative room, the leadership did both, recounting the good old rockets shot 20,000 feet in the air and articulating a zoom-link heavy future. However, their zooming seemed purposeful, to pursue a one-time student payload opportunity, celebrating twenty years of research on the International Space Station.

Indeed, joining this particular club seemed daunting given my lack of mechanical, electrical, aerospace or for that matter any kind of engineering experience. But the club leadership’s resolve to pursue a team-based research opportunity allowed me to find a place within an organization with interests which I initially thought of as wildly different from my own. And in fact, these divergent interests were one of the most positive outcomes of this research project: while I originally joined as a bioinformatician, I branched out to explore more general space microbiology and outreach. At the same time, I placed a great deal of trust in other members of the engineering team to manufacture a stable apparatus to send to outer space, launching an experiment which required every single member of our team.

Our experiment studied the effects of spaceflight on Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Staphylococcus Aureus biofilms. Biofilms are solid three-dimensional structures constructed by bacteria, oftentimes implicated in chronic infection within a wide range of organ systems. Our engineering team designed and constructed an aluminum payload, structurally able to withstand rocket launch, in order to transport these bacteria to the International Space Station, where they were grown for three days. A separate earth control experiment was later carried out with the same equipment.

Columbia Space Initiative Advisor and former NASA Astronaut Mike Massimino,

Columbia Space Initiative and Students from M.S. 302. Photo Credit: Theo Nelson

As our team conducted biological experiments, we also organized significant community outreach to underserved middle school students in New York City in partnership with Sophie Gersen Healthy Youth. We wrote a five-week Introduction to Space Science course, which allowed students at M.S. 126 and M.S. 302 to contribute to our research efforts through hands-on citizen science work. Additionally, we invited students to present their contributions during our spaceposium event, held in Low Library.

More generally, a group research opportunity like this one involves an interdisciplinary team of students working on a question addressing a broadly-relevant topic. In our case, we were interested in exploring biofilm physiology. Each member contributed their particular expertise to the project, and that’s part of what makes group research projects so exciting, as each student serves as both researcher and mentor, as both student and expert. For our project, we had electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, biology and outreach sub-teams which met more frequently to accomplish their given tasks. Successfully completing the project required each of us to step outside of our comfort zone and to give and receive guidance from other team members.

Team Co-Lead Swati Ravi and Biology Advisor Bryan Wang examine a bacterial

payload, which was flown as a part of the NASA SPOCS program to the international space

station for thirty-five days. Photo credit: Theo Nelson.

Grappling with major project decisions is more challenging, as you must successfully ‘pitch’ your contributions to the remainder of the team. You will also likely ‘pitch’ your project to both internal and external funding sources. These additional responsibilities develop managerial and persuasive skills necessary to further your development as a researcher. For example, I pitched that we attempt to sequence the DNA and RNA of our bacteria to see both genetic and epigenetic changes within the biofilms.

Based on my club-based research project, it seems to me that opportunities such as this one prepare young researchers for all sorts of collaborative initiatives. Such initiatives include the National Microbiome Data Collaborative and NASA GeneLab. These organizations themselves provide many opportunities for team-based research, providing exposure to physicians, scientists and engineers from many geographical and topical backgrounds. Within the humanities, numerous crowdsourcing opportunities such as the Library of Congress’s By the People campaign or Columbia Libraries Digital Dante project come to mind.

Depending on the discipline, these team-based opportunities may be more or less readily available. If you aren’t sure whether your skillset is appropriate, then I would highly recommend having a conversation with the team lead for potential insights. Every conversation will further your awareness of your current toolbox and give you the motivation to expand your skillset.

All the best on the research journey!