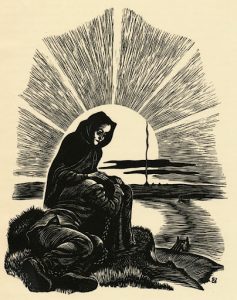

“Sonya comforts Raskolnikov in Siberia,” drawing by Seth Adam Smith. Photo credit: https://sethadamsmith.com/2012/08/04/seeing-the-savior-in-crime-and-punishment/

“Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be still wiser; Teach a just man, and he will increase in learning” (Proverbs 9:9).

It’s a fortunate staple of most undergraduate students’ experiences of the CORE curriculum at Columbia that we run across a Professor who, by the example of his incisive approach to a text, his skills in fostering dialogue, and his openness to the questions of his students, inspires many students to pursue a text, question, or point further than they originally imagined. But, as many of us have discovered through our journey in the CORE, such opportunities to grow in knowledge only manifest to those who are willing to engage in the dialogue in question. Indeed, the words second-semester Literature Humanities’ students hear in the Gospel of Matthew about the Parable of the Sower and Christ’s conclusion “blessed are your eyes for they see, and your ears for they hear” (13:16) ring true once we realize that one idea, no matter how small, can change our entire life if we have eyes to see and ears to hear.

And, it’s this openness to the perennial questions and traditions of the CORE that students invested in the curriculum should share with other peers who might be disillusioned by what the CORE has to offer. Having wavered in my affection for the CORE Curriculum in the past on account of instructors and teaching methods that did not meet my expectations, I know that it can be difficult to see the merits of an educational system focused on discussion if such discussions are lacking or are not engaging. However, all it takes is one friend or Professor who leaves an impression on us due to their love for the traditions, thinkers, and texts of the CORE to instill in us a love for learning for the sake of learning.

For me, this happened when our class read Crime and Punishment in second-semester Literature Humanities. As I later told one of my friends who audited the class, the concluding image of Raskolnikov throwing himself at the feet of Sonia in an act of reconciliation was so beautiful that it called me to a deep sense of awe at Dostoyevsky’s final redemptive act in the story, and our class’s discussion of this scene deeply moved me. For another good friend of mine, it was Aristotle’s Ethics in Contemporary Civilization that roused in her a deep appreciation for the capacity of the CORE to invite us into thinking about the good life. Others will find it while delighting in the melodies of Beethoven’s ninth symphony or pondering the breathtaking architecture of Amiens Cathedral. A part of us yearns for these moments of deep intimacy with the inexpressible beauty of timeless things. It’s incumbent upon us to encourage each other to search for these moments, seeing as with patience, we will eventually find them – or perhaps, in some sense, they will find us.

I think that this encapsulates one of the greatest lessons of the CORE curriculum when viewed at a general level, namely, that we are on a journey together toward a horizon of ever-greater knowledge and the pursuit of truth. That journey is an invitation to which a great instructor or Professor or friend can invite us, but it is a journey which we only take in the company of each other and with a desire of leading each other closer to the truth. In future blogs, I hope to talk about how pedagogical methods and teaching have fostered those invitations in the classrooms at Columbia throughout its history, and what we can learn from the approaches we encounter every time we step into the classroom. For now, we need to remember that we cannot divorce the discoveries made in research and reflection from the texts and the people who made these discoveries possible. As Socrates confesses in Plato’s Theaetetus with respect to his project of fostering new ideas in the minds of the young men he teaches, the new ideas truly belong to his younger counterparts, but they are only brought to fruition through his painstaking labors and questions. The same goes for us – through further exploration, we can take something that really struck us in our conversations in the classroom and pursue it further, but we nevertheless remain forever indebted to the traditions, the lasting ideas, the history, and the people that engendered that discovery.

As we welcome new and returning students on campus and into CORE classes especially, we must remember that this approach to knowledge, an approach centered on preparing people for a lifetime of pursuing the truth, requires a personal invitation. While Professors try to invite their students into the conversation, often some encouragement is needed from peers to participate in these age-old discussions which are challenging but so important. There’s nothing quite like a conversation with friends about Achilles and hubris in the Iliad to pique a potential lifelong interest in that subject that can bear fruit for so many other people. We should never underestimate the transformational power of learning, and we should never underestimate the power that words of invitation, “come and see,” truly have.