“Regarding each of the things we understand, however, we don’t consult a speaker who makes sounds outside us, but the Truth that presides within over the mind itself, though perhaps words prompt us to consult Him” (St. Augustine, On the Teacher).

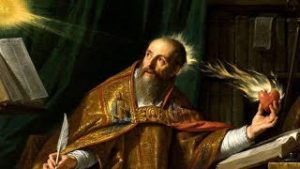

A photo of Augustine of Hippo, from whom I take the first quote, Photo Credit: Painting by Philippe de Champaigne

It seems that many Columbia students have lost a great amount of faith in the process of teaching, in how it can enlighten the mind and bring us to greater contemplation of the truths in the world. No doubt, a lack of a broad understanding of the intellectual traditions of the West contributes to this plight.

But its effects run deeper – when we cut ourselves off from thinking deeply, we fail to see the truths that, poetically we might say, “force themselves” upon us as we dive deeper into the contemplation of the highest things. In the Source Book of the Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West, the product of a series of projects to refurbish and streamline the Core that began in the 1950s, the staff of Columbia College worked to provide a cohesive, well-thought out answer to the dilemma of how to approach the Core for undergraduates was attempted. As the staff wrote in the 1946 Preface to the First Edition, “In view of the present aim to develop the student’s critical understanding of his society, the selections for the most part present specific, important arguments” (v). Its intention was to present to the students a dialogue and its effect on the shaping of Western culture. The purpose of the Source Book was to educate Columbia students on the important books of the West, and, in combination with the Manual to the Core, the Source Book provided a method for understanding the valuable traditions of Western literature and philosophy. As the Committee who formed the 1946 Source Book noted, “The emphasis in these volumes has been deliberately placed on the specifically European institutions and ideas which have helped to shape the character of contemporary civilization”(vi).

The gradual evolution of the Source Book from 1946 to 1960 indicates a lot about what the function of the Core was perceived to be, and how the pedagogical implementation of this was meant to play out. A 1954 revision committee worked to implement new source-readings from “authors and documents hitherto unrepresented: Las Siete Partidas, Goliard Poets, Plato, Plotinus, Camoens, Sepúlveda and Las Casas (The New World), Boccaccio, The Thirty-nine Articles, Bossuet, Diderot, Helvétius,” etc. (vii). The one commonality among these different thinkers seems to have been a genuine investment in considering the traditions of the West, or informing such, and the Committee for the Core noted that these “specific changes” were “made in the interests of scholarship, clarity, and classroom effectiveness” (vii). It was a tradition which students were begged to engage in, and from which many students clearly profited.

Classroom effectiveness with respect to what? Classroom effectiveness with respect to the cultivation of the habits for learning which define the intellectual life. As the staff say, “Nearly every introduction has been shortened and revised so as to provide merely background information and to leave more to the student in analyzing the documents” (ix). The recognition that many authors would be left out of this volume did not preclude the hope that began with the 1946 volume and the hope that “the Source Book a work of useful reference in their later college studies and that it will become a welcome addition to their permanent libraries” (vi). The desire of the staff was clearly that lifelong learning would ground the students in continual pursuit of the highest truths. This hope was clearly successful. When readings began to be integrated in spring 1941, “Results were so encouraging that the readings soon came to be regarded, by staff and students alike, as one of the most valuable features of the course” (v). This spirit of appreciation of the material informed both the pedagogical approach to prioritize the texts as the backbone of instruction and the students’ desire for these works. Additions and revisions to the Core were always focused on preserving this spirit of the Core, this spirit of a continual desire for learning and for illuminating the truths that we have in our inner minds.

I think that, in the final evaluation, revitalizing this same spirit of inquiry for the Western tradition is crucial in revamping students’ dying interest in the Core. And, if this happens, as I noted in my first blog post, the dividends can be truly enormous for our society and our own formation. One of the best Christmas blessings that we can give ourselves is the chance to reopen some old books that we encountered in classes like Contemporary Civilization or Masterpieces of Western Literature. This would be a wonderful use of our time, as it was to the students of the 40s and 50s.