By Guest Contributor Sakshi Aravind, a PhD student at the University of Cambridge. She works on Indigenous environmental justice in Australia, Brazil, and Canada.

In the last week of May, the mining colossus Rio Tinto blasted the 46,000 years old Juukan Gorge rock shelters in Western Australia (WA) during its operations in Brockman 4 mines. The caves were of profound cultural and spiritual significance to the traditional owners, the Indigenous Puutu Kunti Kurrama (PKK) peoples, while also carrying immense historical and archaeological value. Rio Tinto had obtained ministerial consent from the state Minister for Aboriginal Affairs to carry out the blasts under Section 18 of the obsolete WA Aboriginal Heritage Act, 1972 (‘Heritage Act’). In response, the destruction of these culturally significant sites evoked shock and anger around the world. There were calls for addressing the deficiencies in the law, which does not make provisions for consultation with traditional owners or review of the ministerial consent in light of subsequent discoveries. Following this PR backlash, Rio Tinto attempted to recover with apologies and clarifications, although these went in vain. Rio Tinto’s specious regrets were as wicked as its attempts to attribute the blasts to certain ‘misunderstandings’.

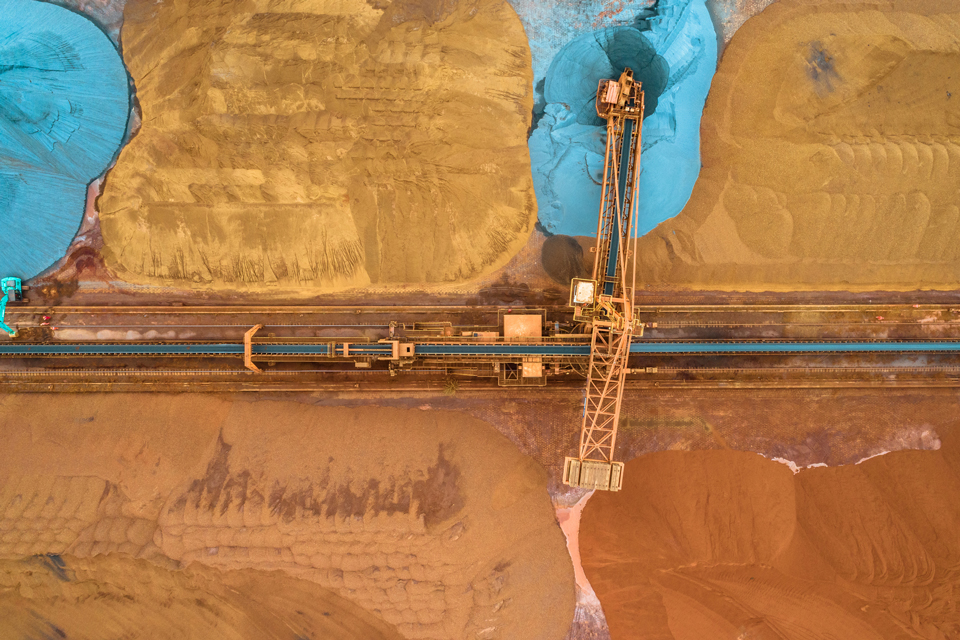

As I have argued elsewhere, these blasts are not a single event of destruction. They are an ongoing process of festering the wounds of settler colonial capitalism, which have never been allowed to heal. The destruction of Juukan Gorge is irreversible damage and an incommensurable loss to the traditional owners of western Pilbara. Further, they reveal a pattern of systemic erosion of Indigenous rights and identities. Rather than an exception, Rio Tinto is only emblematic of the noxious extractivism that has been foundational to the expansion and sustenance of capitalism and colonialism around the world.

Elsewhere, First Nations in Canada have suffered repeated setbacks in their fight for rights over land and sovereignty against mining companies. While treaty rights and Constitutional rights have guaranteed a certain degree of Indigenous participation in decision making, categorically, often Indigenous sovereignty must concede to economic benefits. The recent blockade by Wet’ suwet’ en people in British Columbia against the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline illuminates the challenges of fighting for traditional territories against the combined forces of the State and private corporations.

Brazil has also witnessed relentless destruction of forests and Indigenous territories by mining companies under the aegis of the Federal government, with little or no recourse to legal remedies. To put it plainly, the status of Indigenous rights, sovereignty, and environmental justice have been continually eroding in settler nations.

The ‘duty of consult’, i.e. the obligation to consult and accommodate Indigenous interests in policies and decisions that affect them, has often been conflated with Indigenous environmental justice. It is said to embody aspects of participation and recognition within Indigenous rights framework. Jurisdictions like Canada, with an advanced constitutional recognition of Indigenous rights, have contributed significantly to the jurisprudence around duty to consult. Australia trails far behind in this respect. However, the legal frameworks of settler-colonial nations have only allowed for ‘consultation’ and not unequivocal consent. This approach blatantly fails to address the question of Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty over land and territory, some of which have been better articulated in international rights instruments such as The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (“UNDRIP”).

The UNDRIP in 2007 was a notable political gesture from the state bodies in coming together and recognising the questions of indigenous differences and vulnerabilities. Despite criticisms for its inadequacy or watered-down provisions, the UN Declaration made substantial provisions for adhering to the ‘distribution-recognition-participation’ paradigm of environmental justice amongst other measures for political empowerment.The UN declaration: recognises obligation towards indigenous rights as an extension of the existing Human Rights obligations (Art 1); protects the First Nations from all forms of discrimination based on identities (Art 2); re-asserts the need for indigenous self-determination (Art 3); protects the communities from forceful dispossession from Indigenous land (Art.8 and Art.10); right to free and prior informed consent in any economic/military activities on indigenous lands (Art. 29, 30, and 32). Hardly any of them have made their way into domestic legislation in either Australia or Canada.

As a consequence, Indigenous communities may be heard, but only as a matter of procedural necessity. First Nations continue to be denied the power to veto extractivist projects over their land and resources. Such denial has grave implications for the idea of Indigenous environmental justice. Achieving justice in settler colonial contexts demands truth and reconciliation. These values can only be accomplished by providing an apparatus for substantive Indigenous voices and representation in the social, political, and economic process. In Australia, the Uluru Statement from the Heart and the proposal to amend the Australian constitution to enshrine Indigenous voices in the Parliament is a significant step towards reformulating the idea of justice within a settler State.

Courts have attempted to achieve Indigenous environmental justice through means available to them. For instance, I have argued that in Gloucester Resources v Minister for Planning (Gloucester Resources), the New South Wales Land and Environment Court focussed on the testimony of Aboriginal elders, their connection to the land, and cultural heritage. Although Gloucester Resources was primarily articulated as a climate change litigation launched against the commencement of a coal mine, it had vital contributions to Indigenous environmental justice. While specific case laws cannot realise the idea of Indigenous environmental justice, they demonstrate the significance of ‘listening’ to Indigenous communities to achieve it. The blasts in WA have now provoked us to revisit what justice means. And we must revisit it in settler nations, mindful of the fact that they are established on the dispossession, displacement, and erasure of Indigenous peoples.

Indigenous environmental justice cannot reconcile with extractivism and capitalism, which operate in cahoots with the State and perpetuate the erasure of Indigenous identities. Extractive economies thrive on the severing of Indigenous ties with land and environment. These exploitative idioms of capitalism cannot be remedied with mere ‘duty to consult’, just as the incommensurable loss of Juukan Gorge cannot be restored with trifling apologies or paltry compensations. Australia at this hour needs more than a review of heritage laws. It needs to acknowledge that the nation’s past and present are caught in toxic tangles of settler colonialism and capitalism. The redemption lies in accepting and acting on constitutional reform enshrined in Voice, Treaty, and Truth.