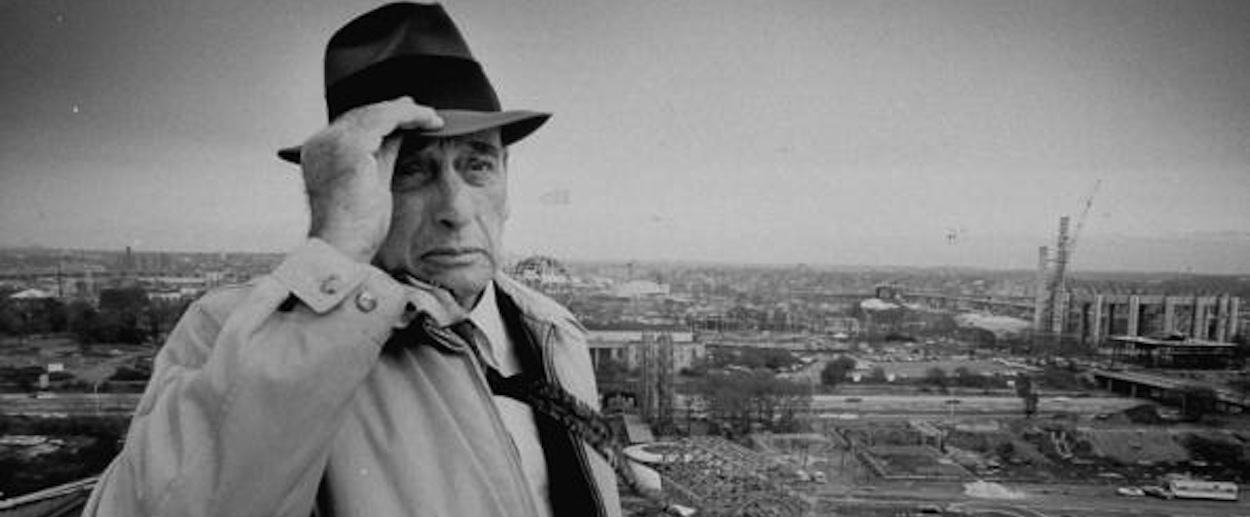

Robert Moses was in many ways the heir to Le Corbusier’s legacy. He was responsible for the transformation of New York City over the course of his five decade career (1913-1968). As the head of numerous authorities, Moses oversaw the construction of twelve bridges, 35 highways, 416 miles of parkways, as well as 658 playgrounds. He also controlled the construction of public housing in New York for some 13 years. An avowed modernist in the vein of Le Corbusier, the works Moses undertook reshaped the social fabric of New York, often to the disadvantage of marginalized communities. As Cedar Lewisohn has commented,

Urban renewal is often justified as the desire to improve the lives of others, but it is mostly just a pretext for the real motive: making money. In New York City, Robert Moses was the driver of this restructuring, with a vision resembling Flash Gordon’s world of glimmering highways and tall towers […]. This combination of modernization and speculation laid waste to once viable communities (Lewisohn, 7).

Robert Moses was responsible for the construction of much of New York’s public housing. When he arrived as construction co-coordinator in 1947, there were some 17,000 units of public housing; when he departed, this number had increased by six fold. It is reported that no construction project went underway without Robert Moses’ explicit approval between the years 1945–1958. Many critics lay the ghettoization of New York at Moses’ feet. Harrison Salisbury described the largest project in the country, Fort Greene, as follows:

The broken windows, the missing light bulbs, the plaster cracking from the walls, the pilfered hardware, the cold drafty corridors, the doors on sagging hinges, the acid smell of sweat and cabbage, the ragged children, the plaintive women, the playgrounds that are sees of muddy clay, the bruised and battered tree, the ragged clumps of grass, the planned absence of art, beauty or taste, the gigantic masses of brick, of concrete, of asphalt, the inhuman genius with which our know-how has been perverted to create human cesspools (Marcuse, 8).

Robert Moses was rumored to have been extremely racist. As such, it is not surprising that the public housing projects he initiated contained the germs of segregation, if only implicitly. The income limits for many of the units constructed by Moses directly after World War II were relatively high, and can be tentatively titled ‘moderate income housing’. This ensured that the middle class, who were primarily white, would remain within the city, while people who fell beneath these income limits were often forced to move to the outer boroughs. Peter Marcuse captures this process brilliantly in his book ‘Robert Moses and Public Housing’:

His title I projects were projects aimed at recapturing areas on the fringes of the central business district, or otherwise ‘under-utilized’ from the point of view of New York’s elites, for ‘higher and better’ uses. Fundamental to the process was the displacement of poor people and their replacement by those of higher income. That shift in residents is sometimes referred to as an unfortunate by-product of redevelopment, but it can better be viewed as an essential part of the process (Marcuse, 7).

This process of displacement was supplemented by the enormous highway projects Moses undertook, which forced another 250,000 people to move. Areas like Rockaway Park, where space was cheap and available, were treated as a ‘dumping ground’. As a result, mass-produced high-rise apartments were erected on an enormous scale, to the point where Rockaway Park, although containing only a fraction of Queen’s total population, contained over half of the borough’s public housing. The projects there were densely populated and contained little retail space. They would come to be occupied by some of the city’s most desperate inhabitants. Not surprisingly, they also predominantly housed people of color.

This process of displacement seems moderately uniform throughout New York. When the east Harlem projects under construction in the 1950s displaced some 1800 local businesses, no effort was made to find them new premises. Robert Moses’ initiatives reconfigured the social fabric of New York: this fabric was rendered inclusive to those with money and economic prospects, while exclusive to those already on the periphery. Joel Schwartz, author of ‘The New York Approach’, a book about urban planning, summarizes this process aptly in saying, “From the beginning, west side liberals could couch the removal of blacks and Puerto Ricans in the language of community balance and cohesion” (Schwartz, 15).