In the 1980s, Graffiti began to penetrate the sphere of fine art in both its guises as graffiti writing, and street art. This entailed a consolidation of many of its themes and motifs. Jean Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring would markedly outpace their contemporaries in this respect, emerging as two of the most famous artists of the latter half of the 20th century. Yet, strictly speaking, they would not have thought of themselves as graffiti artists; rather, they were enormously indebted to its conventions and innovations. It is interesting that in spite of this, academics persist in labeling both Haring and Basquiat Graffiti Artists. Keith Haring persisted in creating street art throughout his career. Basquiat took a more dramatic turn in his artistic trajectory, veering towards neo-expressionism while retaining some of the conceptual concerns of street art. This transition, from the street to fine art, is an interesting one. Due to the limited space on this website, it appears most fruitful to concentrate our energies on his career.

Jean Michel Basquiat was born to a Haitian Father and Puerto Rican Mother on December 22, 1960. The family resided in the affluent neighborhood of Park Slope, Brooklyn. Basquiat came from a distinctly middle class background: his father was an accountant. His mother nurtured his burgeoning interest in art from a young age, taking him to numerous museums; Basquiat supposedly saw Picasso’s Guernica in the MOMA when he was young, which would prove a formative influence on his later work. His story is not entirely congruent with the typical graffiti narrative, replete with its impoverished inner city youth. Basquiat was not impoverished, nor did he live in the inner city.

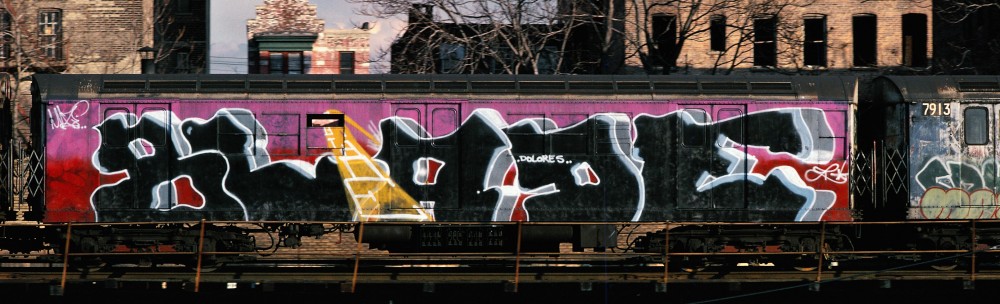

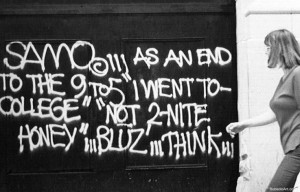

After his parents split, Basquiat moved around with his father, spending a brief period in Puerto Rico, before returning to New York. He moved from school to school, before enrolling in the City-as-School program, where he met future collaborator Al Diaz. While attending the school, Diaz and Basquiat would roam the streets spray painting various different surfaces with the word SAMO, which was an acronym for ‘Same Old Shit’. While Diaz and Basquiat would spray paint subway trains—particularly the D train—and other surfaces, what they were doing was not strictly speaking graffiti writing. Rather, one could call it street poetry. The SAMO tag would often be accompanied by a message – it sought to engage the viewer:

“SAMO AS AN END 2 NINE-2-FIVE

NONSENSE

WASTIN’ YOUR LIFE

2 MAKE ENDS MEET…TO GO HOME

AT NIGHT TO YOUR

COLOR TV…”

In 1978, Basquiat left home for good. He started hanging out with prominent Graffiti artists, such as Lee Quinones and Fab Five Freddie, exchanging ideas largely about music and art. The same year, Basquiat approached Andy Warhol to sell him some of his postcard art. In December of 1978, The Village Voice published an article celebrating SAMO. Slowly, Basquiat began gaining recognition for his gifts.

By 1980, Basquiat started having his work exhibited in the context of fine art. This began with the Times Square Show of 1980, followed by the New York/New Wave Show of 1981. He befriended Andy Warhol shortly after. Not long after this, Basquiat exhibited in Europe for the first time. His work began to be covered by prominent art magazines such as Artforum. His career took off from here: in 1982 he is given a solo show in Los Angeles at the Gagosian Gallery; he also exhibited alongside the likes of Anselm Keifer and Andy Warhol in the international exhibition ‘Documenta 7’. By 1983, Basquiat was regularly working with Warhol, and travelling all over the world. The next year saw the young artist grace the cover of the New York Times magazine. Basquiat’s ascendency in the art world was marked throughout by his heavy drug abuse. In 1988, he finally overdosed.