Graffiti is a politically potent act. In a sense,

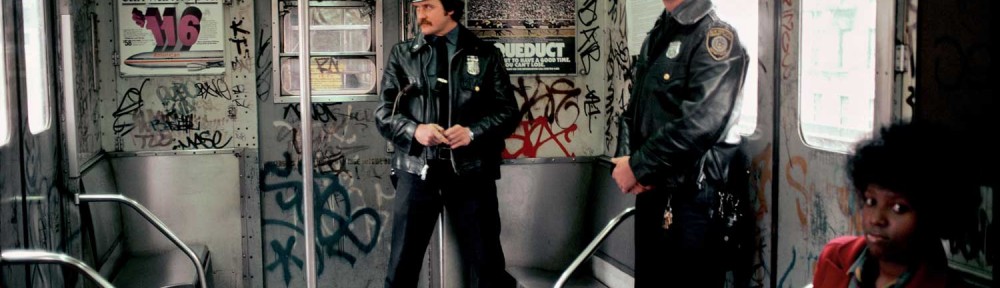

Graffiti writers are at war with the urban developers, the architects, and all the other faceless decision makers. The city walls stand for ownership and authority, and graffiti is the voice of the unelected, fighting, back against the systems that are imposed on them” (Lewinsohn, 87).

Graffiti is subversive insofar as it involves a flagrant disregard for one of the primary tenants of industrial capitalist society, namely, property rights. Graffiti rejects the notion of private property—anything is fair game. It also uses public space in ways not intended by city planners, destabilizing any notion of a porous, inclusive civil society. It begs the question: who is this civil society for? It hints at the inherent particularism, and moreover, elitism, in the kind of universalist rhetoric espoused by western liberals. It speaks, voices, and articulates in the face of its own marginality. It is a speech act for the oppressed.

Michel de Certeau has much to say on this matter. In his seminal book ‘The Practice of Everyday Life’, De Certeau explores how he panoptic logic of modern city planning conditions how we move, how we express ourselves, and ultimately our very subjectivities through a variety of spatial and ideological strategies. Yet, the everyday man—the subaltern of modernity—is imbued with the ability to creatively reconfigure space, and utilize it in ways that were not intended by the panoptic logic of the state. De Certeau saw walking in this vein; insofar as it elides, skips and turns, walking functions as a sort of speech act, imparting a semblance of agency where there appears to be none. In an almost more immediate sense, Graffiti creatively reconfigures space in a similar manner. It allows the subaltern to speak.