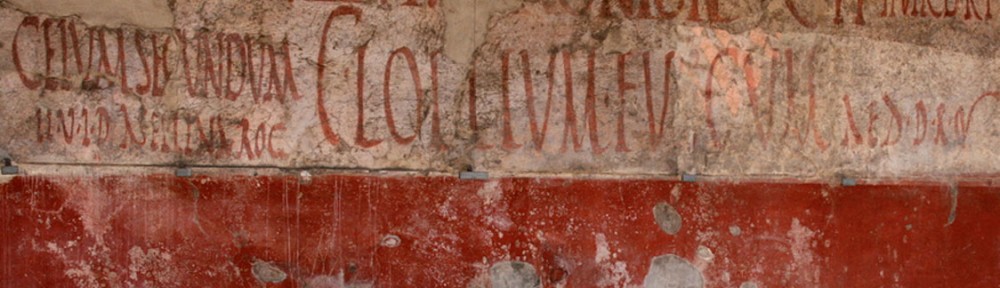

Graffiti is by no means a modern phenomenon. Although we can find traces of what we presume to be graffiti as far back as ancient Egypt, there is no proof that these are in fact unauthorized drawings. We do know that graffiti was a widespread practice throughout Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, where surfaces, spaces, and buildings were defaced in order to articulate particular political messages. From the beginning, it seems, graffiti is imbricated with politics.

The word graffiti itself is derived from the Italian word “graffito”, meaning ‘little scratch’.“Graffiti” is the plural form. Today, it is understood as “any form of unofficial, unsanctioned application of a medium onto a surface” (Lewinsohn, 15) The practice seems to have been widespread during Elizabethan England, and even the Romantic poets are said to have taken a liking to graffiti, Wordsworth having written the poem ‘Lines Upon a Seat in a Yew Tree’ (1795) about a deceased man, who in his youth etched his name onto a tree overlooking a beautiful view. By the Victorian era, graffiti had gained a negative reputation, associated with the mores of the lower classes. It was marked as a socially deviant practice.

Modern Graffiti comes into its own in the late 1960s, when it became a creative act unto itself; beforehand, it was associated primarily with gangs and the marking of gang territory. For Cedar Lewisohn, it is “rooted in the creativity of the dislocated and alienated urban communities of America in the second half of the twentieth century” (Lewisohn, 8). Graffiti by its nature defies commodification; it is unauthorized, and utilizes public space for its own ends. Yet under the purview of graffiti, there is a marked distinction between graffiti writing and street art. Although they overlap in many respects, these practices are largely divergent in terms of authorial intention, as well as form and function, Moreover, the techniques and intended audience are often different as well.

This distinction is essential to any attempt at reviewing the vast corpus of graffiti art created in the past half century. Indeed, many graffiti writers would object to the term ‘artist’ to begin with. Graffiti writing’s primary concern is with typography, and letter formation in the guise of ‘tagging’. It is usually only comprehensible to other Graffiti writers: it does not attempt to create a dialogue with the wider public. Tagging is interlocutive, but only in an exclusive sense: it communicates with those already versed in the particularities of the sub culture. Graffiti art is not for you. It is an empty signifier, a statement that asserts nothing other than its very existence. Some intuit it as a form of anti-art in the vein of Dadaism, where tagging is seen as an aestheticized form of vandalism. Others see it as a co-option of corporate logic, where creative faculties and capacities of the given graffiti writer are reduced to a brand in the form of the tag; content is reduced to the minimum, where emphasis is placed instead on scale and repetition.

Street Art is different in this sense. It explicitly seeks to communicate with its viewers, through its use of an expanded repertoire of images and motifs. It is legible. Its tool cupboard is not confined to the marker and the aerosol can; it often utilizes stencils and pasting as well. In this sense, street art can be seen as populist: it is concerned with the masses. These are necessarily broad characterizations; some see street art as everything on the street that is not graffiti. Others, such as the artist John Fehner, see the distinction as fundamentally predicated upon class: “If you had a degree, you did ‘street’ art’ as opposed to graffiti” (Lewisohn, 18).

While Street Art is greatly indebted to Graffiti Writing, and can certainly be said to be contained within the wider category of Graffiti, it also seems to have its own distinctive historical lineage. Many street artists are greatly indebted to the progenitors they found in the form of the Mexican Mural Movement. Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jose Clemente Orozco all sought to make art that actively engaged the public about issues of suffering, social justice, and modernity at large. Committed Socialists, these artists focused on subjects that were acutely political, utilizing public space in order to communicate their various messages. Additionally, The Federal Art Project, the visual arts arm of the Worker Progress Administration (which was the largest New Deal Agency that existed during the Great Depression in order to revitalize the economy) also sponsored artists throughout America, including Jackson Pollock, and set precedents for public art in the United States.

These processes of inscription (graffiti writing vs. street art) are analogous, but also fundamentally different in the sense that one seeks to establish a dialogue where the other does not. While both graffiti Writing and street Art often situate themselves vis-à-vis modernity and it various institutions and techniques, graffiti writing seeks to subvert where street art attempts to critique.