• “How and Why Did Genocide Become a Non-Political Crime” by A. Dirk Moses (Professor of Global and Colonial History (19th-20th centuries), EUI)

Tuesday, September 23rd

4:00PM to 6:00PM, 411 Fayerweather

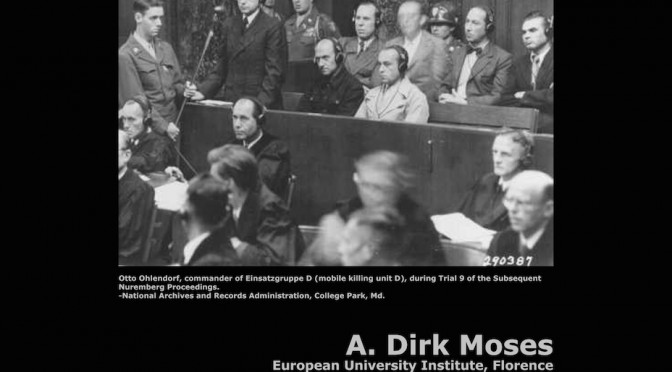

International law distinguishes between political and the non-political crimes in the following way: racial hatred is defined as non-political because victims are attacked for who they are: for their identity. Genocide cannot occur where a victim group has agency, as in, say, launching an insurgency, because such action implies politics. This conception of genocide as a non-political, mass hate crime is modeled on the Holocaust of European Jewry, meaning that Holocaust memory intersects in important ways with the humanitarian intervention agenda. To galvanize the “will to intervene,” human rights activists must make contemporary civil wars resemble the Holocaust by casting civilians as victims of murderous racial persecution: for who they are rather than for what some of them may have done. The spurious distinction between racial and political intentions—the depolicitization of the genocide concept—lies at the heart of the relatively new field of genocide studies and its older sibling, Holocaust studies. One consequence is the promotion of toleration as genocide’s antidote. Another is that genocides are misrecognized, as in the case of the UN Darfur report in 2005. In this paper, I explain how and why this distinction was constructed by revisiting the contingent origins of the genocide concept. My discussion mainly concerns two moments in the second half of the 1940s when it was crystallized in international law and the postwar imagination: 1) the latter Nuremberg Trials; and 2) the concurrent UN Debates about the Genocide Convention.