Editor’s Note: This piece was written in July 2018.

By William E. McCracken with Jonathan B. Kim

When Bill McCracken joined CA, Inc. (NASDAQ: CA) crisis management was at the forefront. The company was recovering from a serious case of fraud—one that called into question the organization’s future. During his initial tenure as Chairman, Bill’s primary concern was rebuilding the company’s board. Later, as CEO, the course CA charted would shape his view on activist board governance.

Sometimes an experienced coach needs all the backing he can get to turn the fortunes of a struggling team. In 2005, I joined the Board of Directors of CA after 36 years at IBM. Shortly thereafter I was elevated to Non-Executive Chairman. At the time the company was operating under the burden of a deferred prosecution agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice, including an outside monitor to oversee its compliance.

I quickly realized we were at a critical stage in the never-ending lifecycle of the board. As a result of mandatory retirements and term limits, nearly half of our directors had departed or were reaching the end of their tenures.

But we didn’t just need to fill vacancies. We also needed to transform the board’s mindset. The prevailing culture of public companies in the mid-2000’s limited their full engagement. Passive acceptance of the CEO’s game plan was largely the rule of the day. Rapid changes in the market-place, however, including more aggressive questioning of corporate leadership by shareholders, drove a need for more active director participation. In short, every board needed a deeper understanding not only of their company but also the competition, industry and technology shifts, and their impacts on the viability of short and long-term corporate strategies. This much-needed change to boardroom culture and behavior, where directors felt free to pose tough questions and express disagreement amongst themselves and with management, was critical to CA.

To set the stage, CA retained a consultant I had used in my IBM days—a professor from the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine—to compile leadership and behavioral profiles on each director and director candidate. Obtaining buy-in to this approach wasn’t easy since it involved peer-to-peer reviews. Nevertheless, we all found the resulting Myers Briggs and 360 assessments helpful in reconstituting the board. A critical part of this transformation was thinking of the board as a team of individuals who each brought their own diverse experience and skills but all in the name of collective improvement. As our consultant often said, “Our differences make us whole”.

THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEWPOINT: CULTIVATING A NEW CORPORATE CULTURE

When it comes to corporate culture, I’ve always believed that the board should be a leading participant, creating an ethos in the boardroom that sets the right tone for the entire organization. In terms of engagement, the board must be willing to challenge management more actively and constructively rather than confrontationally, in the same way a demanding coach challenges players to reach beyond their physical and mental limits.

CEOs, as coaches in their own right, must occupy a middle ground and must accept that working with a highly engaged board will be difficult on occasion. Why? Because CEOs and their management teams typically expend enormous amounts of time and energy developing corporate strategies. By the end of the process, they’ve filtered and funneled their thinking to the best of their abilities. At that point why would any CEO want an activist board second-guessing management’s playbook?

I’ll tell you why. Because an activist board (activism in this context not to be confused with hedge fund or shareholder activism) will consistently stress-test management’s overall strategy and strategic alternatives before they see the light of day and before such approaches and decisions are invariably stress-tested by outside forces: namely analysts, investors and competitors, all of whom will be far less forgiving if results miss expectations.

When I relinquished my CA Chairmanship and took on the role of CEO at the beginning of 2010, my now activist board challenged me time and again. Often I didn’t like or appreciate these challenges. Nor did my management team as the internal stress-tests of our proposals had an inevitable trickle-down effect. As is often said about the most successful athletic teams, however, half the reason for their success was that the practices were tougher than the actual games.

Case in point. In early 2008, CA created a taskforce consisting of a handful of independent directors and senior managers. Working with an outside consultant, their mission was to examine CA’s business strategy. Historically, CA had been a mainframe business, an important player in that sector but no longer an innovator. As one article noted, “[In 2009,] CA’s own customer polling… revealed a company that was top three in terms of mission critical, but bottom five when it came to strategic importance”. CA was being disrupted. The growth of the internet and dynamic changes in the behaviors of customers, employees, and in the IT market generally were challenging CA’s long-term strategy and its viability as an organization.

By the end of 2009, after concluding that a new direction was needed to revive a company that had suffered a series of debilitating body blows, we decided to reorient CA’s focus and presence in the marketplace. And this change was to be accomplished without adversely impacting our dominant mainframe business. We needed to embrace what we saw as the future: cloud computing. Specifically, we wanted to move our products to that environment to enable our customers to operate in the previous main-frame orientation as well as the cloud. This required our board and management to set aside the then conventional thinking around our products and to embrace new ways of doing business.

As an organization, CA did more than just respond. It underwent a massive change in its culture and long-term strategy. Starting in 2010, the company undertook a major initiative to move into the cloud computing business, getting a jump-start on competitors.

THE CEO’S VIEWPOINT: EMBRACING A PROACTIVE BOARD

When I took over as CEO of CA there was no putting the board back in the bottle, so to speak, or in reversing course in terms of the organization’s strategic direction. And frankly my management team and I wouldn’t have had things any other way. Efforts were already underway to acquire in excess of $1.5 billion in new companies over the course of 36 months. From our perspective it was essential for the board to have a central role in the process to allow them to function as participants in the corporate governance of the company as opposed to spectators on the sidelines. In other words, the CA team needed the board’s engagement and total commitment to a new playbook, ideally without Monday morning quarterbacking.

Mission one for the board through this transition was its role in our procurement of the right skills and capabilities to execute on CA’s cloud strategy. Fundamental to this mission was the formation of a M&A Committee of the board composed entirely of independent directors. The purpose of the Committee, a liaison between management and the board as a whole, was to ensure that the company was executing on the new strategy while at the same time avoiding the urge to micro-manage day-to-day details. For example, given the large number of proposed M&A transactions needed to establish our lead in cloud technology and expertise (twenty-two by my count), as CEO I was granted discretionary authority to pursue acquisitions of up to $50 million without prior Committee (or board) approval. Such authority allowed CA to secure a succession of key acquisitions at an accelerated pace without the typical fits and starts associated with a multi-layered system of reviews and approvals.

A second, and equally important, role for the committee was post-transaction oversight to ensure that the assimilation of any acquired firm was working as intended and producing the intended returns, and to ensure that future transactions incorporated all relevant lessons learned.

From the beginning both the board and I accepted that as CEO I was the primary manager and motivator of the CA executive team. But I wasn’t being given a blank check to execute on a new game plan that would make or break the company. As regular progress reports from the M&A Committee made their way to the board I was prompted by individual directors and the full board to justify our acquisitions and the benefits received. A set of key performance indicators was established to measure our progress, and the board examined our performance against the KPIs at every meeting. The purpose of these exchanges was to ensure that the company stayed on course with its new direction and to confirm that both management and the board had considered all stakeholder concerns in the process.

THE LINK BETWEEN STRATEGY AND CAPITAL ALLOCATION

One of the biggest tests we faced was from CA’s shareholders. The approach we took proved constructive as the board and I chose to reach out and engage with our investors from the beginning—and more importantly to listen to their thoughts on capital allocation in light of CA’s new direction. Early on, the board received signals of concern from investors. “This is our money you’re spending. How’s the return looking?” Rather than simply accept management’s response to growing shareholder anxieties, the board probed beyond investor concerns to ask “what is our capital allocation strategy, and why is it right?” In response, management undertook a three-month effort to understand all aspects of the question raised by our investors and directors and put forth a proposal that was accepted by the board following an series of intense discussions. As noted in our public statements at the time, the board and management were confident after debating the proposal that we could both return capital to shareholders while continuing to invest in our future growth.

In late 2011, with over $1 billion in free cash flow even as CA reached the height of its planned M&A activity, the board approved an enhanced capital allocation program aimed at returning up to $2.5 billion in excess capital to shareholders through the end of Q1, 2014. The return would consist of an increased dividend and stock repurchases. Both the board and I regarded the move as a reasonable balance between the expressed concerns of shareholders, who’d been urged to stay with CA for the long haul as the results of our turnaround began to emerge, and the need for CA to avoid, to the extent possible, any unnecessary diversion of management attention and capital resources to issues beyond our strategic transformation.

During this capital allocation review, an activist investor in the company’s stock called for CA to return even more capital to shareholders. The Chairman and I met with the investor. Because we had already begun an effort around our capital allocation strategy, we were ahead of his requests. My comment to the board after that meeting was, “This activist doesn’t know it yet, but we’re going to make this guy a hero.” In the end, given the board’s early and proactive engagement with investors—particularly around strategic and capital allocation issues—the company was able to work with the activist towards a quick resolution, without compromising CA’s long-term strategy.

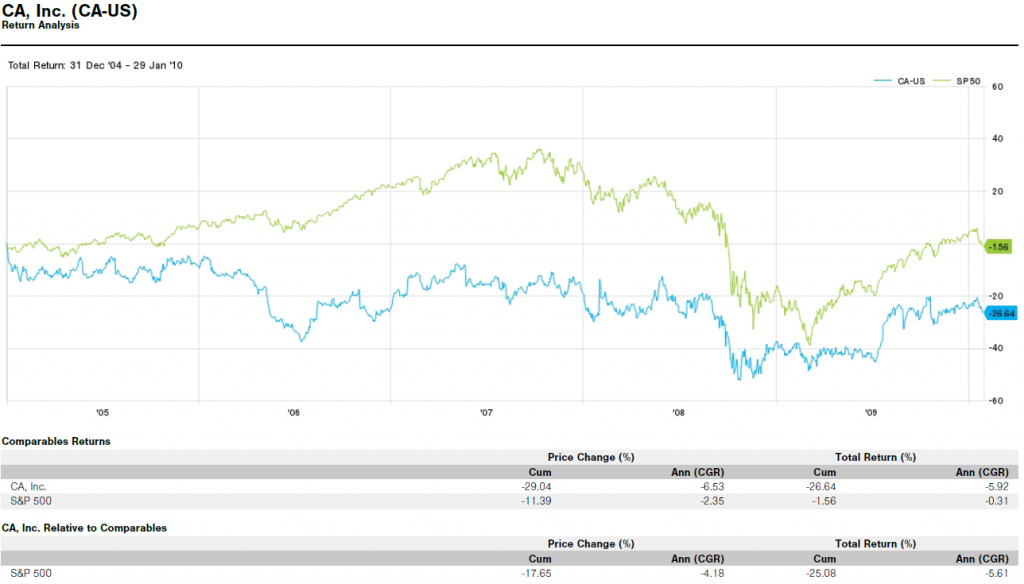

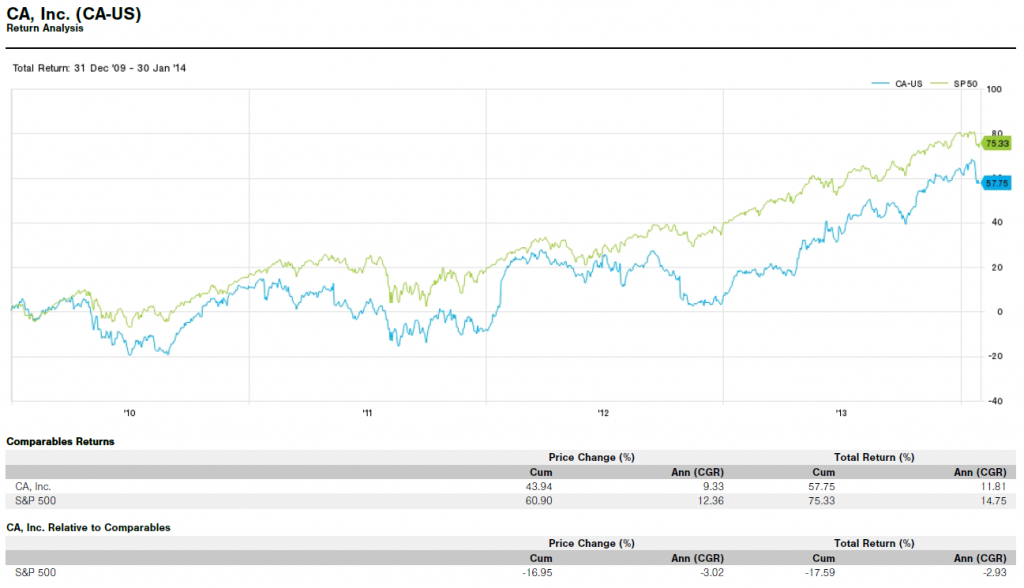

Return analyses reflecting the performance of CA, Inc. vs. the S&P 500 during Bill McCracken’s tenure.

WHAT HAPPENED AT CA – THE SEEDS OF ACTIVIST BOARD GOVERNANCE

Reflecting on my experience at CA, one lesson was clear. The reconstituted board that I had helped to shape as Chairman, and that guided the company through a major period of crisis and transition to an entirely new and highly profitable business model, was much more than the typical oversight body. When I accepted the role of CEO, my successor as Chair asked me, “How do you think it’s going to be working with this activist board?”, to which I replied, “I expect it will be a challenge.” And it was. As an involved and forward-thinking group they routinely pushed me as CEO, and the company as a whole, to perform better.

But what, exactly, was the board doing to drive this change? The prevailing governance model when they embarked on their mission was no different than before. The investor base of the company was fundamentally the same. Yet the board’s actions were dissimilar from the rubber-stamp bodies of an earlier corporate era. The CA board behaved differently and confronted their oversight duties with a different mindset. And this was acutely apparent to me in my role as CEO.

This difference in behavior and mindset are what define an activist board—again not to be confused with hedge fund activism. An activist board proactively engages management on strategy, the options the company has to consider, and, when it comes to it, poor performance. The key here is that an activist board is proactively and constructively thinking about the long-term future of the company and the decisions that it needs to be taking now to create that future. There are, unfortunately, too many examples of activists that fail to act in the company’s interest, but instead look to cost reduction, leverage, and other financial tactics to return money to shareholders in the short-term at the expense of the company’s long-term success.

To be clear, increased involvement from shareholders and others in corporate governance isn’t a bad thing. It is, or should be, a welcomed development. But the shift in power and authority at times to those within the corporation such as imperial CEOs, and more often these days to those on the outside, does make the job of the board more challenging and demands more involvement by directors.

LESSONS LEARNED

So what did I learn from my time as Non-Executive Chairman and later CEO of CA?

First, the board must be well-informed about the company, the industry and the competition. It can’t rely on management alone for such information and must be willing to look to outside sources when necessary. Formation of a combined board and management task force was only the first step in getting the influencers at CA to work together. The outside consultants that assisted the task force shared some hard truths with us—namely in the form of analyst, investor and industry opinions of CA—and the initial reports were not always flattering. They were, however, necessary for us to self-examine our then-current course and to reset our future direction.

Second, the board must be deeply engaged in the company’s long-term direction from a managerial and strategic point of view. Again, the goal isn’t to micro-manage the CEO and senior management but rather to actively challenge them to justify actions and decisions that carry long-term consequences. The board, along with management, should be able to connect the company’s short and long-term strategy in simple, declarative statements. CA’s pursuit of new blood on their board was part of this equation. But pursuit of a new mindset, or tone at the top, for all new and continuing directors was perhaps the more important variable. That is because it set an example for everyone at the company from senior management on down to follow.

Third, the board must be actively engaged in overseeing how the company’s assets are being deployed for the future—stress-testing management’s proposals in practice before the actual contests on the field begin. And by assets I mean all company resources, from financial capital to human resources and skills and beyond. At the end of the day the coach may call the plays. But without the backing of everyone in the organization from the front office to the file room even the most successful coaches may find it difficult, if not impossible, to compile a winning season, much less a turnaround.

But why should CEOs embrace this call to action? Because it’s necessary to their survival in the modern world. It’s essential for a CEO to be challenged by an activist board because constructive confrontation helps to prepare the CEO for the sustained growth of their company and for any tests of their leadership. As I’ve said repeatedly, embracing a partnership with an activist board yielded untold dividends for me as well as the company I managed by making me a better and more effective CEO. As a management team develops and refines its strategy, it is a natural tendency to become convinced of that strategy and direction. An activist board can expand the aperture for management and may just be the catalyst for the company to disrupt itself before the market forces the company to reactively pivot.