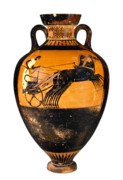

Panathenaic Amphora Depicting Four-Horse Chariot Race. Kleophrades painter, 490-480 B.C., Photo Credit: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

My final Contemporary Civilization paper was entitled “Creativity and the Core.” It ran through Plato’s metaphor of the soul as a horse-drawn chariot; Foucault’s description in Discipline and Punish of an execution by dismemberment – being pulled apart by horses; and the criticism of modernity, taken up by Christopher Lasch and Hannah Arendt, as producing disjointed selves in a disjointed society. I ended with reflections on the modern university, and on Columbia’s Core curriculum. I suggested that the Core is perhaps best regarded neither solely as an essential survey of an authoritative canon, as some might argue; nor as an outdated study of an intellectually oppressive curriculum, as others might say; but as a toolbox of ideas that frees us from reinventing various intellectual wheels by giving us a conceptual vocabulary grounded in history, and that both sets a literary and philosophical bar for us and helps us reach it. In short, students should care about the Core because it serves as grounds for creativity, especially (I argued) expressed through writing.

I stand by this argument, although personal experience suggests that, ironically, the Core class many students are least passionate about is the one devoted to writing. When I tell my friends that University Writing was my favorite part of the Core, I am invariably met with general disapproval. I’m not entirely serious when I say this – I complained about my P3 paper as much as anyone – but I do value University Writing, less for the experience I had taking it as for its merits in hindsight. Looking back, I see that UW signposted the process of scholarly writing that I learned to adopt in time, assuring me from the outset that the slow, sometimes maddening process of drafting an argument, only to rewrite it entirely, was not an anomaly, but the heart of the writing process.

By unsettling the linear “five-paragraph essay” mindset in favor of a recursive writing process that remains perpetually open to new changes and inspirations, UW brought the process of scholarly writing closer to another world that is dear to me – that of creative writing. Creative writing is circular. You may not know a character’s defining trait until you’ve finished your first draft, and then have to start over again: just as when you finish a fifteen-page paper and discover the key point of your thesis in your last paragraph. By encouraging this process, UW also suggests the possibility of a true “scholarly conversation” – a term whose overuse perhaps belies its surprising accuracy.

There is nothing quite like a good conversation. College famously hosts many of the best conversations, sometimes disparaged as “bull sessions” – conversations that escalate alarmingly fast into considerations of God, meaning, society, and everything else, where we are both marvelously self-aware, arguing at the top of our rhetorical form, and completely unself-conscious, unembarrassed by our faltering attempts to get at the truth. These conversations surmount one of modernity’s besetting problems, alluded to in (for instance) Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse: the problem of communication, the notion that a true meeting of minds between individuals is rare, perhaps even impossible. Augustine tells us of just such a conversation with his mother in Confessions 9, suggesting that these conversations have been going on for a long time. Long may they continue.

The scholarly (and creative) writing process, at its best, replicates such conversations, disregarding boundaries of time, place, and discipline. In my CC paper, Plato and Augustine argued with Foucault and Arendt. When W.E.B. Du Bois, in his famous quote, speaks of sitting with Shakespeare, implied is the complex understanding emerging from careful reading and writing and study. The Core curriculum gives us the names and faces of the speakers around the table, inviting us to join the debates and digressions that intrigue us – but this point applies beyond the Core. A sure sign of progress in my research, whether in Classics or East Asian Studies, is when I walk into a conversation, when my sources begin cross-referencing, refuting, or agreeing with one another. While my two majors may seem to occupy separate worlds, the way to bridge that gap for me is often through creative writing, scripting literal dialogues between ideas as characters: engineering, for instance, a conversation between Socrates and Laozi in central Asia, as I had the chance to do for a recent final project.

To summarize: by exposing us broadly to major texts and jump-starting the scholarly writing process, the Core equips us with the intellectual tools we need to appreciate conversations within and across disciplines, and to enter those conversations with creative contributions of our own. If we can become skilled conversationalists, steeped in history and all its allusive power, always presenting our points well but never afraid to revise them – if we can become creative scholars and scholarly creatives – then Columbia will be far stronger for it.