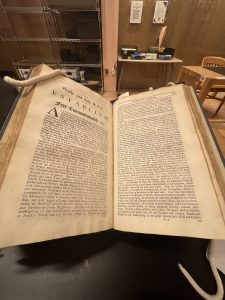

Examining a text in RBML. Photo credit: Elliot Hueske.

Research settings look different for everyone but relying on textual resources and supporting documents to substantiate a claim remains consistent throughout all research types and environments. Nonetheless, finding a place to start with respect to navigating Columbia’s many libraries or connecting with a librarian can feel overwhelming. Afterall, Columbia has twenty-two libraries that feature extensive and diverse collections of digital and print resources to guide your research. Although I am fond of Avery Library, I have also found myself gravitating to Butler 310 reading room and trying to stake out a table on the mezzanine level. In this post, I hope to offer some insight regarding using the libraries throughout your research and discovering what might be considered their hidden gems!

- Go to Butler’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML)

Everyone should go at least once to the RBML on the sixth floor of Butler Library during their time at Columbia. In order to visit, you must arrange an appointment in advance by connecting with a curator via their website. Organizing a time in advance is necessary because the librarians have to make sure that the item you are interested in is available and prepared for you when you arrive. Interacting with a first or second edition folio, pamphlet, or manuscript is an incredible experience and can provide new perspectives regarding your subject matter. For example, I was studying John Milton’s divorce tracts for a paper and wanted to read his work in a 1697 edition. I was told that the folio originated from the collection of Samuel Johnson, Columbia University’s first president. Although the divorce tracts were approximately the same in both editions, I soon discovered that this early version might offer some insight that I could not access through contemporary versions. As I was flipping through the pages, I came across three dried flowers that had been pressed between the pages. To think that these might have survived centuries tucked within the binding of a folio was a truly compelling notion. Yet it was reading Johnson’s marginalia that was most helpful. Johnson’s annotations indicated that, despite differing political ideologies with Milton, he deeply admired Milton’s rhetorical strategies, theories of moral life, and conceptualization of ethical training. Through reading this intellectual interchange between Milton and Johnson, I was able to better grasp the broader impact of Milton’s work. A side note… there are many early editions digitized through the database Early English Books Online (EEBO), but it is truly not the same experience as interacting with them in person! - Connect with a librarian

This may seem like a straightforward suggestion, but I often find that many people hesitate to reach out to a librarian directly for support with their research. Columbia librarians are incredibly knowledgeable about the texts that inhabit their collections, and they are some of the first people that you should contact if you are having trouble with starting your research project or finding relevant material. Scheduling a consultation with a subject specialist can be done through the Columbia Libraries website (CLIO). However, there are also alternative paths in which to connect with a librarian including emailing questions or visiting during drop-in hours. Their expertise can really help to enrich your project with compelling supporting documents.

- Use CLIO and the ILL System

Research during COVID felt impossible, but the online collections of Columbia’s libraries (accessible through CLIO) helped me overcome the challenge of not being able to visit libraries in person. Most of the materials that I needed to access were early editions of 17th century manuscripts. Through the library databases I was able to request scans that were delivered to my account within days. Some of the material that I needed was not within Columbia’s collections. Nonetheless, I was able to request it from our peer institutions using the ILL, or Interlibrary Loan System, to acquire scans of relevant documents.

All this to say, the libraries are an incredibly helpful resource that you should take full advantage of when conducting your research. Furthermore, this is not an experience isolated to humanities research. In fact, Columbia’s Health Sciences Library has many first editions of science writing including Hooke’s Micrographia and other fascinating texts on chemistry, biology, physics, etc. I would strongly encourage all Columbia students to use the libraries when conducting research and hopefully interface at least once with a rare book.