Arturo Isla Archives, Photo Credit: Eli Andrade

This winter break, as I pieced together the beginnings of my senior thesis on Arturo Islas’s novel The Rain God (1984), I stumbled upon an archival treasure trove—M0618, the “Arturo Islas Papers.” Comprising a hefty 56-box collection, M0618 chronicles four decades of the Chicano author’s life, documenting his turbulent romances at the height of the AIDS crisis, his intimate struggles with his own deteriorating ill body, and the unresolved family trauma that often shadowed his existence.

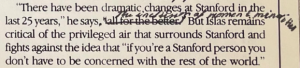

Having suffered a ruthless childhood under his authoritative macho father and his body faltering after contracting polio, Islas turned to pursuits of the mind as a way to escape the physical constraints of his dysfunctional family and sickly body, becoming the first Chicano PhD student, and later professor, at Stanford University. At a time when universities were largely white spaces, Islas championed diversity and inclusion. In a clipping of Stanford Profile, Islas candidly addresses a misquotation that had attributed to him the statement, “There have been dramatic changes at Stanford in the last 25 years…all for the better.” With discerning clarity, he takes a corrective pen to the narrative, scratching out the optimistic coda “all for the better” and inscribing above it the truthful amendment: “The inclusion of women & minorities.” In this seemingly minor act of revision, Islas not only corrects the record but, more significantly, underscores his commitment to diversity, refusing to obfuscate the university’s long history of exclusion with vague and performative rhetorical tactics.

When diving into the archives, these small details astound me the most. While I could easily access the digital repositories of the Stanford Profile from the comfort of my own home, they would regrettably fall short of encapsulating the historical resonances of Arturo Islas’s handwritten corrections. Islas’s personal journals, correspondence, and manuscripts offer a tangible connection to the specific cultural and political climate of the 60s, 70s, and 80s, an era frequently presented in pedagogical contexts through an impersonal lens, characterized simply by its political tumult during the Civil Rights Movement, the ascendancy of Black and Brown power, and the Vietnam War. However, delving into the inner workings of Islas’s intellectual and personal life shifts this historiographical narrative from a detached chronicle of events into a humanized and nuanced history narrated by individuals with firsthand experience—individuals who were directly impacted and often silenced by prejudice from telling their stories. In this way, Islas’s journals, letters, and manuscripts act as a bridge, connecting the broader historical panorama of the late twentieth century with the intimate intricacies of an individual grappling with the complexities and challenges of his time. It is in these artifacts that the historical becomes personal, and the personal political, providing a textured and humanizing lens through which silences are heard and histories reformulated.

Having spent three days at Stanford’s Green Library, where the Department of Special Collections houses its archives, I was able to crack open the life of an author whose work I had long admired. My investigation began way before I had stepped foot in the archives. Though I had previously read Islas’s novels and the literary criticism surrounding them, my curiosity was particularly spurred by the semi-autobiographical nature of Islas’s novels. As an author who intricately wove elements of his own life into his narratives, employing fiction as a medium to probe unresolved traumas, it was paramount for me to discern the intersections where reality and imagination converged. The plot of The Rain God, as a vessel for Islas’s self-disclosure and therapeutic exploration, guided my research as I noted the porous boundaries between fact and fiction. As I sifted through his journals and correspondence, the parallels between Islas’s literary creations and his own life easily disclosed themselves, revealing that a significant portion of The Rain God was more autobiographical than purely fictional.

Navigating the labyrinth of Islas’s narrative landscape, it became evident that his literary endeavors transcended conventional delineations, inviting scholarly examination into the intricate dance of truth and imagination within his semi-autobiographical novels. Though I was familiar with Islas’s professional and academic background, exploring M0618 unearthed a sense of responsibility that beckoned me to treat Islas’s deepest concerns with the care that had long been denied to them. The research process felt increasingly voyeuristic as I moved from newspaper clippings and lighthearted postcards from friends and family to heartbreaking letters and nude photographs from lovers, therapy transcripts, and even suicide notes. The intensity of these documents made me question my own role as a scholar and researcher. Who was I to poke around someone’s private life like that? And, even if Islas had left the public with a fictionalized account of his life, why had I violated his generosity and gone looking for real-life evidence to ‘corroborate’ the events that had clearly traumatized him? Perhaps a shroud of fiction was necessary for Islas, but as a scholar, I searched for truth.

After three days, I bid farewell to Stanford and M0618, laden with notes, memories, and a newfound appreciation for archival research, carrying with me Islas’s triumphs, tales, and preoccupations. Though I still have many unresolved questions, I now feel captivated not only by Islas’s novels but by his personal life as well. As I continue to write my senior thesis, I hope to distill my findings at Stanford’s archives and reconstruct Islas’s story, placing him firmly within a literary tradition that seems to have forgotten him. For now, this is how I view my role as an archival researcher.