On the first day of Literature Humanities or Contemporary Civilizations, you were probably asked to ruminate on what a canon is. Responses to this question vary, yet they typically conform to two distinct categories. Some students hew to the orthodox conception of a canon as a repository of esteemed cultural texts, while others advance

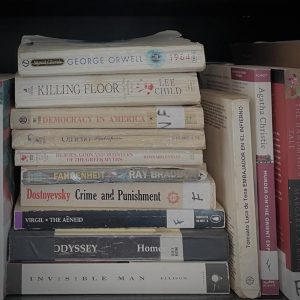

A few foundational texts, Photo Credit: Eli Andrade

a more nuanced viewpoint, considering the canon a compilation defined by individual subjective judgments of cultural significance. Thus, the initial quandary that asks us to define the canon, must also always ask why the preeminence of white males and their works are the quintessential cultural exemplars of the West. This discourse reveals a prevailing skepticism within our cohort concerning the Western canon, primarily because of its historical proclivity to overlook the contributions of women, the working class, and individuals of color. As the semester unfolds, this conviction is only further crystallized as we find ourselves grappling with odd and archaic viewpoints like Aristotle’s “The slave is what he is by nature” (1260b40) or Rousseau’s notion that “the whole education of women ought to be relative to men..to please them, to be useful to them” (352). We, students, itch to rectify these age-old discourses, to participate in and create a philosophy that is mindful of people’s identities and histories—the token gesture to conclude with a singular lecture devoted to the themes of race and gender is not enough.

Therefore, I believe the more pressing question among students is: What should we do with our racist, misogynist, and elitist canon? Amidst a range of suggestions, one always stands out as the most radical yet supported: a complete upending of the Western canon and the end of the Core Curriculum. While this abolitionist call seeks to solve the problem by getting rid of the texts and authors that perpetuate the canon’s white male-centric view, it is ultimately an ineffective solution—we cannot simply evade the historical context that grants us the privilege to attend an institution of higher learning like Columbia University.

Rather than censoring the canon, we must cultivate compassion and the ability to critique the texts that have shaped Western society. In doing so, we not only change how we learn from the canon but also how we approach the socio-political issues that plague our society. As W.E.B. DuBois puts it, “honest and earnest criticism from those whose interests are most nearly touched,—criticism of writers by readers,—this is the soul of democracy and the safeguard of society” (28). We, Columbia students, are the “readers,” and Aristotle, Hume, and a plethora of other revered Western thinkers are the “writers” we must critique for the benefit of modern society. By taking their ideas and adding our viewpoint we make way for novel ideas. This synthesis, ultimately, underlies the academic research process in which we contribute to the scholarly conversation by building upon the ideas of those who came before us.

Although I sympathize with many of our classmates’ frustration, the current struggle for the diversification of the canon hails from the same historical struggle that anti-racist initiatives and feminist frameworks seek to rectify. In no other area of social justice do we shy away from confronting the harsh truths; instead, we seek to bring those truths to light and to think critically about their implications. Likewise, the intellectual struggle that is the formation of an appropriate canon needs a similar reckoning. Though their works may be obscure and limited, it would be a mistake to believe that women, people of color, and working-class individuals have not contributed to the intellectual history of the past. We must seek them out and amplify their voices, add them to the already well-established voices that we so often encounter. However, simply finding them is not enough, we must engage them with other thinkers and treat them with the same importance. As Aristotle asserts, “the end aimed at is not knowledge but action… [because] knowledge brings no profit; but to those who desire and act in accordance with reason, knowledge…will be of great benefit” (1095a10-12). Thus, our ultimate goal is action, concrete social change that instrumentalizes knowledge from a variety of sources, including that of the canon.

At best, we can critique the ideas of those who came before us and try to find writers that suit our tastes. Even better, we can survey the intellectual landscapes of the past and present to formulate our own ground-breaking thoughts to contribute to the future—we can be active agents within a rich and complex intellectual history. At the end of the day, this is what the core curriculum seeks to teach us all, and who knows, maybe one day, our revolutionary writings will be next on the list of required CC texts.

Citations

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by David Ross, Oxford University Press, 2009.

Aristotle. Politics. Translated by Joe Sachs, Hackett Publishing Company, 2012.

Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. The Souls of Black Folk. United States, A.C. McClurg & Company, 1904.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Emile: Or, Treatise on Education. United States, Appleton, 1905.