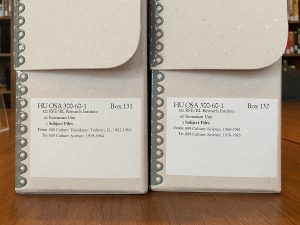

Archival boxes at the OSA. Photo credit: Teresa Brown

While in Budapest and working at the Open Society Archives, I was paired with a junior researcher who works primarily on the history of cybernetics (the science of communications and control systems in both machines and living things) during the Cold War. I was given a project to investigate how the archive catalogs materials relating to the history of science, specifically within their collection of documents from Radio Free Europe’s Research Institute.

The collection of documents from RFE’s Research Institute is one of the OSA’s largest and most well-known collections. A very important radio station during the Cold War, RFE was run by the United States and broadcasted to Eastern Bloc countries. The OSA contains 18,767 boxes of documents from RFE’s Research Institute. This collection, “HU OSA 300 Records of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty Research Institute”, is divided into 19 categories. These are then divided into anywhere from 1 to 30 subcategories. Each subcategory contains a list of boxes, anywhere from a few to over 800. A box contains roughly 1-10 folders, and each folder contains anywhere between one and hundreds of individual documents. (And this is only the OSA’s collection on RFE! They have many other collections, ranging from international human rights violations to propaganda films and photograph collections.)

If this seems overwhelming, it can be. But the key to successfully making use of an archive is to conquer its filing system. Many archives employ cataloging systems that are simply preservations of existing systems. Take for example a modern-day company that wishes to begin an archive of their work. Their work is likely already organized, say based on department, and an archive would likely preserve this order. An interested researcher would then be able to look up a department name and an employee name and receive a stack of documents. What makes the OSA’s filing system interesting is that it is artificially constructed. The OSA’s filing system, specifically for the RFE Research Institute collection, is not based on any pre-existing order. Rather, the OSA received an enormous mass of documents and had to come up with a system to organize the material. My job was to go through all of RFE’s folders in the Romanian unit that could possibly contain materials related to science and record the type of information they actually contained. Essentially, I was tasked with assessing the transparency of the OSA’s catalog system by investigating one small part of their collection.

Some of what I found in the hundreds of folders I looked through was exactly what I expected to find. The folder labelled “Culture: Science: Medicine” contained reports on the shortcomings of soviet healthcare, the status of health services in Romania, birth rates, children’s healthcare and population trends. All of the articles and reports fit the label they had been given. Other folders were less predictable. The folder labelled only “Culture: Science” (i.e. it did not have a third, more specific scientific subcategory in its label name) contained all manner of radio monitoring reports and newspaper clippings relating to anything vaguely scientific. This seemed to be a catch-all folder, but what baffled me was that, in my opinion, there existed more specifically labelled folders that all of the documents could have been filed under. This somewhat odd system suggested that the archivist who did the filing may not have been a specialist in the history of science.

More broadly, different people will have different opinions on what the best archiving system is, but ideally a solution can be reached that is accessible and clear to most researchers. After all, a central goal of an archive is to construct a system such that a researcher can find what they are looking for–-no small task if we’re talking about finding one or two documents amongst hundreds of thousands. At the same time that good organization is paramount, as a researcher, one of the benefits of going through many folders of material is stumbling across documents you otherwise might not have found.

By looking through thousands of documents on the history of science in Romania I found a single typed summary of a newspaper article about two mathematics conferences in 1950. I had no idea these conferences existed, but this document suggests that the researchers at RFE were interested in how Eastern European media reported on the conferences. As an applied math and history double major, I was excited to come across material on the intersection of math and history. The idea of examining how media sources collected and disseminated information on mathematics intrigued me. I now plan to use this document as the starting point for my senior thesis – an investigation into the role of media in the politicization of events of mathematical importance. As much as it is important to have efficient filing systems, sometimes when you have to do a little digging you stumble upon even better material that you may not have known to look for in the first place.