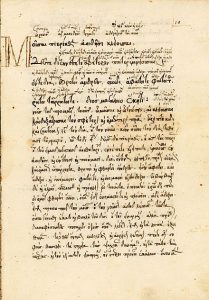

“A Greek manuscript of the beginning of Hesiod’s Works and Days,” photo from John Tzetzes (Wikipedia).

“The words of truth are naturally simple” – Euripides, The Phoenecian Woman

The history of the formation of the course now known as Literature Humanities is not a well-known story among students at Columbia College nowadays, and this is a regrettable reality. A great deal of thought for over a century has been invested into forming the curriculum as it was taught for decades, and there have been many developments in the philosophy behind many methods for teaching the course that are related to the changes that the course underwent during one particular episode of change in 1937.

Prior to 1937, the bulk of the Core Curriculum was Contemporary Civilization, which was a course focused primarily on the key philosophical texts of the Western tradition. A committee established in 1934 eventually drafted a proposal in 1937 for an inaugural two-year program, in which one would study key books in the Humanities under the courses Humanities A and Humanities B, with Humanities A focused on a “great books” curriculum. This was described in Herbert Edwin Hawkes’ now famous letter entitled “The Evolution of the Arts College: Recent Changes at Columbia” as the product of “an evolutionary rather than a revolutionary process” and thus “a gradual movement of judgment and opinion in a given direction through a considerable time” (33). Because the objective of the reform was to permit a natural outgrowth of the Core Curriculum rather than a stark rupture with the past methods of doing things, a combined method of instruction in which the hallmark of Contemporary Civilization would be incorporated into a two-year progression with the two new Humanities courses was established.

The distinction between an “evolution” rather than a “revolution” is something not only crucial for students to take into account when examining the Core, but it is also a defining feature of the intended methods of instruction within the Core Curriculum itself, and especially in Literature Humanities. This is a view in some ways analogous to Edmund Burke’s conception of a gradual modification of the political structure of the state which requires holding onto and respecting the traditions of the past in his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Indeed, Hawkes’ line of reasoning was similar to Burke’s – in the interest of avoiding a “violent overturn of procedures,” Hawkes emphasized the importance of the preceding development of the Committee on the Core’s gradual plurality of interest in creating a new course of instruction for students (33). Out of a deference for the way that things were running, Hawkes and others seem to have made the patient decision to take their time.

This might seem to now be an outdated mode of pushing for reform in the Core, but it was actually a very important contributing factor to the view of the purpose of courses such as Literature Humanities that still has surprising relevance to an ideal approach to instruction and learning. While itself an innovation, Literature Humanities was meant to focus on “readings in, not merely about, the greatest masterpieces of literature,” necessitating that the “first third, or perhaps more, of the first year will be devoted will be devoted to the literature of Greece and Rome” (37). The timelessness of these works is prioritized and emphasized as an indelible quality of the Core, and its relevance for students for Hawkes could not be overstated. He writes, “It is felt that a course of this kind, emphasizing as it does the literature which has through the ages meant the most to mankind, will serve as a basis not only for future attention to these fields in the upper College, but will carry over its values to the years following graduation” (37).

Hawkes hoped that this would be effected through not merely exposure to the texts but also through the competence of many faculty members who were trained in these fields and through the supervision of faculty well-experienced with Contemporary Civilization who were intent on modeling the Humanities A curriculum on many of the successes of its predecessor course. Hawkes’ praise for Contemporary Civilization as “perhaps the most potent intellectual stimulant and the most effective basis for advanced study that we have ever been able to provide” (35) is hard to match, but his hope that the new Humanities course might provide a similar “sound and broad and vital basis on which to build his further scholarly work stands out as palpable in his writing” (35). This, for Hawkes and presumably the plethora of his like-minded colleagues, transformed Contemporary Civilization into something which went beyond a mere survey course. It was now an invitation, in his own words, to “induct the students as early in their career as possible into the intellectual life” (35).

I don’t think it’s an impossibility for us to imagine applying this mindset which was articulated nearly a century ago to our own approaches to learning and teaching in the classroom, even though some students may be compelled to ask why this is necessary. As I mentioned in my previous blog post, only eyes which are willing to see and ears which are willing to hear can be initiated into the sort of intellectual life that Hawkes envisioned, but that intellectual life is not non-existent even if it is dormant in most cases. If we were to re-emphasize the importance of these Greek and Roman texts which contain extraordinary truths about human beings within them at the level of both students and teachers, and we were to emphasize the benefits of teachers having some background familiarity with the texts, then this invitation into an intellectual life which many of our friends and colleagues have pursued would be spurned less often. It wouldn’t require much of a change – just a concerted effort of rediscovery and perhaps a slight shift in the general perspective that people bring to the Core. But, it would help us to rediscover the teaching and learning methods that assisted so many who have come before us in pursuing and I daresay reaching the truth.