By guest contributor Haley Son*

On 14 June 2021, for the first time in over a decade, South Korea’s lawmakers agreed to hear proposed national laws geared toward protecting the fundamental human rights of LGBTI people. While these bills have garnered international support, prospects for passage of an anti-discrimination bill are dim due to intense lobbying by conservative factions and faith groups. Given the challenges of LGBTI equality under South Korea’s legal framework, an alternative avenue would be for corporate Korea to implement LGBTI rights based on global standards in the meantime.

South Korea, the world’s 10th largest economy, still has no laws preventing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, making it a rarity among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in that regard. The South Korean Constitution, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the “UDHR”), sets forth global human rights standards, such as establishing legal equality between the sexes, and prohibiting political, economic, and social discrimination on the basis of sex, religion, or social status. However, while the United Nations has since clarified that LGBTI people are subsumed within the protected status set out in the UDHR, no such clarification has been made in South Korea. The National Human Rights Commission Act, enacted in 2001, does include “sexual inclination” in the definition of the term “discriminatory act of violating the right of equality” (Article 2), but the Act provides no enforcement power (the National Human Rights Commission created thereunder may only recommend non-binding relief measures).

In South Korea’s historically homogenous society, LGBTI individuals face open discrimination in employment, family, and society. Same-sex marriage remains illegal, and in plans to widen the definition of family, the government has excluded LGBTI partners, making adoption near impossible. Furthermore, while LGBTI soldiers are permitted to serve in the military, they are open to criminal prosecution and lack any protections against abuse. Further, conservative groups have continually sought to strip the Commission of its mandate to protect LGBTI rights. Thus, Korea has no legal framework enabling LGBTI individuals to have recourse when they face discrimination. In sum, South Korea’s LGBTI communities have not yet achieved the same fundamental human rights the national constitution affords the general population.

However, the current lack of legal framework for LGBTI rights conflicts with South Koreans’ rapidly changing perception of the LGBTI community. Last year, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea reported that 88.5% of those surveyed supported an anti-discrimination law and 90% endorsed protections of LGBTI employees in the workplace. In 2018, the percentage of those who believe homosexuality should not be discriminated against fell below 50% for the first time after a sharp 15% decrease between 2007 and 2017. The South Korean youth have been a powerful voice for social justice in the past decades, evident by the stark age differences regarding opinions on LGBTI issues. 79% of those between 18 and 29 years old believe that homosexuality should be accepted, compared to 82% in the U.S. However, only 23% of South Koreans over 50 years old agreed with the same statement versus 64% in the U.S..

Despite shifting public opinion, it is unlikely the government will be able to lead the charge for LGBTI rights in South Korea due to immense political obstacles. For one, the conservative Christian lobby, which is increasing in power and has already blocked numerous bills, believes that outlawing LGBTI discrimination is a slippery slope toward the legalization of same-sex marriage. Moreover, the LGBTI community lacks true allies even within the progressive Democratic Party. Several politicians on either side of the aisle have neglected LGBTI rights for the sake of maintaining “social harmony.” In 2020, Democratic Rep. Lee Sang-min announced his plans to introduce a similar anti-discrimination bill, but his proposal granted exceptions if the discriminatory act is related to religious beliefs. Months later, another bill failed to pass after a lack of support from President Moon-Jae In and the rest of the left-wing party. Prior to taking office, President Moon clearly defined his position against homosexuality, saying during a press conference that he “did not like it.”

Against this backdrop, it would behoove corporate Korea to elevate LGBTI workplace rights to relevant global standards. For one, Korean businesses have embraced globalization and are well attuned to international perceptions. For instance, the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the “UNGPs”), celebrating their 10thanniversary this year, have been adopted by major Korean conglomerates such as Samsung and SK. Under the UNGPs, LGBTI workers enjoy the same fundamental workplace rights as set out in the UDHR. Specifically, Article 11 of the UNGPs requires that businesses “avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved.” Article 12, in turn, imposes on business enterprises the responsibility “to respect… internationally recognized human rights – understood, at a minimum, as those expressed in the International Bill of Human Rights,” which, according to the commentary thereto, “consist[s] of the “[UDHR] and the main instruments through which it has been codified.”

The UN has since carved out distinct global standards governing LGBTI rights which “build on” the UNGPs: namely, the Standards of Conduct on Tackling Discrimination against LGBTI People (the “UN LGBTI Standards”). These Standards require (1) respect for the human rights of LGBTI workers; (2) elimination of workplace discrimination against LGBTI employees; (3) support for LGBTI employees at work; (4) prevention of discrimination and related abuses against LGBTI customers; and (5) support for the human rights of LGBTI people in the community.

Given the increased support for LGBTI rights on the part of South Koreans at large, Korean corporations would benefit greatly from adopting the UN LGBTI Standards as part of their corporate social responsibility activities, which companies have begun to emphasize in recent years following increased competition from multinationals. Google Korea was among the first firms to fully promote “fair treatment and equality towards homosexuals in Korea”, kickstarting similar commitments from smaller local companies.

Corporate Korea can also look towards the U.S. to see further possible benefits of these LGBTI-friendly policies. In 2017, 91% of Fortune 500 companies implemented anti-discrimination policies along the lines of the UNGPs despite there being no protections of LGBTI workers in U.S. federal law. As a result of more inclusive standards, the U.S. economy retained nearly an additional 8 billion dollars a year due to increased loyalty from customers and employees. Despite endorsement of the UNGPs by large Korean companies, few, if any, have adopted these LGBTI Standards. Just as corporate Korea took a frontline role in globalizing the South Korean economy, it may well do the same in bringing LGBTI rights on par with global standards.

* Haley Son is involved in refugee and migration rights in South Korea where she is Managing Editor of the upcoming book Voices From The North and a research assistant at The New York Times Seoul Bureau.

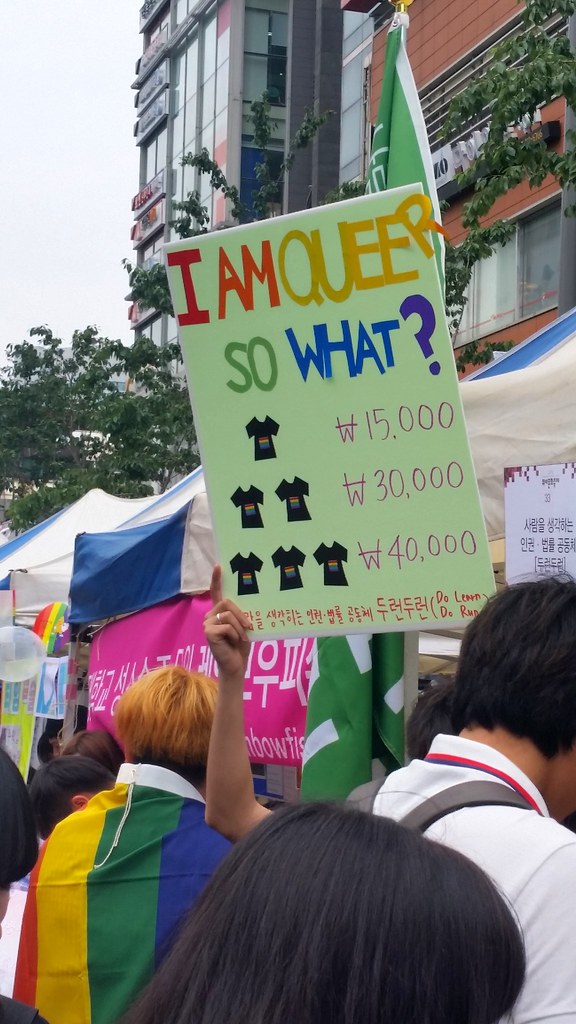

Photos

“LGBT Pride Parade” by cezzie901 is licensed under CC BY 2.0