By guest contributors Abhishek Ranjan* and Shruti Yadav*

This year in March, Germany lined up in Duisburg for their first Group J qualifying match against Iceland, donning jerseys with letters spelling ‘HUMAN RIGHTS’ embossed on each jersey. Norway’s players organized a protest of the same kind in the same week

before their match against Gibraltar, wearing T-shirts with the message “Human rights, on and off the pitch.” During the national anthem, the Norwegian players also raised five fingers in reference to Article 5 of the Human Rights Act, which stipulates that “everyone has the right to liberty and security of person.”

The 22nd FIFA World Cup, which will be held in Qatar in 2022, has been the subject of intense scrutiny and controversy since Qatar was given the right to host the quadrennial football tournament in 2010. The hosting rights acquired by this Gulf nation have

often instigated disputes ranging from accusations of misconduct in tenders and acquisition of rights to allegations of mass atrocities and the geopolitical turmoil in Qatar.

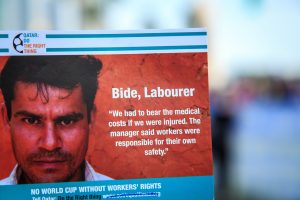

With less than 500 days until the 2022 World Cup. European national teams and nations from other continents have embarked on their quest for glory. These preparations are being carried out amidst the ongoing scrutiny of Qatar which is far from subsiding. As criticism escalates, teams come under pressure from activists and fans to express dissatisfaction with discriminatory legislation and working conditions for migrant workers who are preparing the Gulf country for kick-off on November 21 of next year.

BACKGROUND

Qatar has never had the best reputation for its human rights values and treatment of migrants. These initiatives by the players come on the heels of a report published on February 23, by the British newspaper, The Guardian, which stated that at least 6,500 migrant workers from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka had died in Qatar. The report shed light on the fact that ever since Qatar was granted the right to host the World Cup ten years back, migrant workers have died in the country, with the scorching hot environment, and working and living circumstances being cited as probable causes.

Out of 6,500 dead migrant workers, the number of migrant workers from India is 2,711 – which is the highest among these five countries. Since Qatar was given the right to organize the 2022 FIFA World Cup in December 2010, there have been, on average, deaths of 12 migrant labourers per week. Although according to the report, there’s no necessary implication to suggest that their death bore any relation to the ones working at the World Cup, however, it does find a correlation between the two and quotes a spokesperson for a labour rights organisation who claims that a considerable number of people who died were solely there for the purpose of preparing for the international event. Furthermore, according to The Guardian’s analysis, heart or respiratory failure is the most prevalent cause of death among those who died of “natural causes.” According to the data acquired by The Guardian, “natural causes” accounts for 69 percent of fatalities among migrants from India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, with Indians accounting for 80 percent of the total.

The British newspaper reported particular cases involving the deaths of several workers. Ghal Singh Rai, a Nepalese national, paid more than 1000 euros in recruiting fees to get a job as a cleaner in a complex that housed construction workers for the Education City World Cup Stadium. He reportedly committed suicide a week after arriving. Mohammad Shahid Miah, a Bangladeshi immigrant in Qatar, was electrocuted in his residence after flowing water came into touch with electrical wires. Madhu Bollapally, 43, of India, died of “natural causes,” although his family said he was in excellent health. According to Qatari officials, 80 percent of Indian migrants who died did so of “natural causes.” This wording is said to cover up many occurrences of cardiac or respiratory attacks induced by intense heat or hazardous working conditions.

PREVIOUS ABUSES AND RIGHTS VIOLATIONS

There have been mass protests against harsh working conditions, particularly during the summer when temperatures soar as high as 50° Celsius i.e. 122 degrees Fahrenheit, wage abuse – including on the site of a World Cup stadium – and the lack of rights afforded to migrant workers, who account for nearly 95 percent of Qatar’s population.

Jamie Doward writes for The Observer that ever since Qatar’s World Cup bid was approved, a total of 400 Nepalese migrant workers have died in the construction industry in Qatar. Moreover, according to Pakistan’s embassy in Doha, 824 Pakistani citizens died in Qatar between 2010 and 2020. Government data collected in the investigation by The Guardian shows that between 2011 and 2020, there were 5,927 deaths.

Amnesty International claimed in 2009 that migrant workers, who make up a sizable percentage of the Qatari workforce, were subjected to abuses and exploitation by employers and were poorly protected. Women migrant labourers were especially vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, including beatings, rape, and other forms of sexual assault. In 2007, over 20,000 migrant labourers were reported to have fled from their employers due to salary delays or non-payment, excessive work hours, and terrible workplace environments.

Amnesty International claimed in 2009 that migrant workers, who make up a sizable percentage of the Qatari workforce, were subjected to abuses and exploitation by employers and were poorly protected. Women migrant labourers were especially vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, including beatings, rape, and other forms of sexual assault. In 2007, over 20,000 migrant labourers were reported to have fled from their employers due to salary delays or non-payment, excessive work hours, and terrible workplace environments.

Other than this, various allegations had surfaced alleging that migrant workers in Qatar are exposed to harsh working conditions and have also been subjected to “slavery.” When the International Trade Union Confederation claimed in 2015 that over 1,200 workers had died while working for projects related to the World Cup, the Qatari government had dismissed the charges as unfounded. Later, in order to be transparent in the eyes of the international media, Qatar’s government announced that it will discontinue its ‘Al-Kafala’ system after being pressured by the United Nations’ International Labour Organization (ILO).

WHAT IS AL-KAFALA?

The Kafala system or Sponsorship Law has been synonymous with ‘modern-day slavery’ as it prohibits workers from switching jobs or even leaving the country without their employer’s consent. As a means of responding to the uproar that was caused over FIFA 2022 World Cup’s relocation, the Qatari government signed an official cooperation agreement with the ILO pledging to eradicate the Kafala system. However, various reports have surfaced, claiming the agreement to be simply on paper and nothing grounded in reality despite being signed almost two years back. In light of such reports, there was a vehement demand to relocate the 2022 World Cup from Qatar.

INSENSITIVE APPROACH

Over the last 10 years, Qatar has launched an extraordinary development programme, focusing mostly on the sporting event scheduled for November and December 2022. Seven new stadiums, as well as dozens of accompanying facilities and infrastructure, were built in this Middle Eastern country. A new airport, as well as highways and bridges, public transit systems, hotels, and other lodging amenities, were among them. To achieve all of this, workers were purportedly asked to perform superhuman efforts, with little to no regard for their health and safety.

However, all of this still wasn’t enough to stop FIFA from awarding the 2022 event to Qatar, which defeated the United States with 14-8 votes in the final round. The appropriateness of this questionable decision can simply be derived by requests for a rerun of the vote by a former senior FIFA insider, Alexandra Wrage, which was followed by revelations that former Vice President, Jack Warner was guilty of accepting bribes from former Qatari football official Mohamed Bin Hammam.

Theo Zwanziger, a current member of the Executive Committee, downplayed it as a ‘blatant mistake.’ However, soon enough, Warner and Mohamed Bin Hammam’s careers at FIFA came to an end disgracefully after they were implicated in a corruption scandal regarding Bin Hammam’s candidacy for the presidency of the international governing body in 2011.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE DONE

First and foremost, the Qatari Government should abolish the necessary requirements in the Sponsorship Law that mandates foreign migrant workers to get the authorization of their current employer before switching jobs and in order to leave the country. In accordance with Article 2 of ILO Convention No. 87, it should also amend the Labour Law to allow all migrant workers, including domestic workers, to form or join trade unions.

It should amend Article 3 of the Labour Law, to an extent, in order to ensure that all workers – including domestic workers and other excluded categories – have their labour rights protected by law, equally. It should ratify the ILO Convention 189 on Domestic Workers, and incorporate its provisions into domestic law, and implement them in law, policy, and practice. At the same time, the government should pass legislation that provides specific protective measures to ensure that the rights of domestic workers are fully respected, compliant with Convention 189 on Domestic Workers and other relevant international standards.

WAY FORWARD

Till the time such measures are adopted, there exist several convincing grounds for the tournament’s relocation from Qatar to a more deserving country. The question that needs to be answered is, whether the second-largest sporting event in the world, succeeding the Olympics, should be hosted in such a country. In all likelihood, no.

It is well known that now the World Cup can’t be relocated in just a year. The damage has already been done. But history will remember this as a World Cup built on blood.

* Abhishek Ranjan is currently a second-year law student pursuing B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) at Dr. RML National Law University, Lucknow. He is a content writer and researcher. His academic interests particularly lie in Human Rights Law, Public Policy, International Relations and Minority Rights.

* Shruti Yadav is a first-year law student pursuing B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) at Dr. RML National Law University, Lucknow. Her areas of interest include Human Rights, Foreign Relations and Diplomacy with a newfound love for Criminal Law.

Photos:

“Rusia entregó el relevo de la antorcha de la Copa del Mundo a Qatar.jpg” by Russian Presidential Press and Information Office is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Marchers call for labor rights” by Omar Chatriwala is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Qatar is growing fast” by Omar Chatriwala is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Protesting migrant rights” by Omar Chatriwala is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

hey Larissa Peltola,your article successfully conveys the excitement, passion, and global magnitude of the World Cup.