By Reem Katrib, Staff Writer for RightsViews

With the mark of the 10th year anniversary of Michelle Alexander’s powerful book The New Jim Crow at the end of January, our current celebration of Black History Month, and an approaching presidential election, it is important to bring to the forefront the continuing systemic racism in the American criminal justice system. The recent eighth presidential debate, argued the evening of February 7, 2020, in New Hampshire, brought forth this topic with the spotlight on presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg when asked why a black resident in South Bend, Indiana was four times more likely to be arrested for the possession of marijuana than a white resident after his appointment to office. While Buttigieg had initially avoided the questions posed by ABC News’ Live News Anchor Linsey Davis, he then conceded, claiming that the arrests made were made as a result of the gang violence that was prevalent in the black community of South Bend, causing the deaths of many black youths. This logic and rhetoric, however, plays into narratives which contribute to the disproportionate criminalization of black Americans, despite Buttigieg’s recognition of systemic racism in the criminal justice system on the national level. This then begs two questions; primarily, what policies on mass incarceration impact persons of color today? And what positions have the democratic presidential candidates taken on such a pervasive issue?

A History of Mass Incarceration in the United States

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

The 13th Amendment of the United States Constitution was ratified on December 6, 1865 and deems slavery unconstitutional, except as a punishment for crime. While the ratification of the 13th amendment was meant to abolish slavery, a mythology of black criminality continued to be perpetuated through a white nationalist narrative that took alternative, but just as harmful, forms to target black Americans. Movies such as “The Birth of a Nation” (1915),which was responsible for the rise of the Klu Klux Klan, committed to a narrative of black criminality that many white people wanted to tell. White people wanted to continue to benefit from the “loophole” in the 13th amendment; more so, the movie depicted them, and specifically members of the Klu Klux Klan, as “valiant saviours of a post-war South ravaged by Northern carpetbaggers and immoral freed blacks.”

Slavery in the 19th century and continuing discrimination, violations and abuse, and segregation policies such as those of the Jim Crow era have led to generational trauma and the dispersion of black communities from the south. These human rights violations have not ceased with time but only have changed in nature; systemic oppression against people of color has continued through carefully nuanced political policies that only propagate these violations as systems of protection. The mass incarceration of people of color, which has fed into the prison industrial complex, reasserts systems of racial discrimination and the policing of those marginalized. While not slavery by name, the mass incarceration of people of color acts as slavery in practice.

Although the United States has the highest rate of incarceration at 25% per cent, it only constitutes 5% of the world population. This is a massive statistic, yet, as Alessandro Di Giorgi articulates, “the sheer extension of the correctional population in the United States does not convey the race and class dimensions of the US penal state—the result of a four-decade-long carceral experiment devised from the outset as a political strategy to restructure racial and class domination in the aftermath of the radical social movements of the 1960s.”

The Civil Rights movements that began in the late 1940s were countered by efforts to criminalize black leaders such as Fred Hampton, Assata Shakur, and Angela Davis. In the 1960s, President Nixon emphasized “law and order” and synonymized crime and race through a “war on drugs” in which drug dependency and addiction were regarded as a crime, a rhetorical “war” that disproportionately targeted poor, urban neighborhoods occupied by primarily people of color. Through this syntax of subtle and thinly veiled racial appeal, matched with backlash towards the Civil Rights Movement, the Nixon campaign deployed the “Southern Strategy,” which aimed at gaining the votes of lower income white people who had previously voted with the democratic party. This strategy utilized the war on drugs as a top-down approach to gain the support of the white people who had felt isolated and alienated with the dismantling of the Jim Crow laws on racial segregation.

The war on drugs was only strengthened in later years, especially with the election of Ronald Raegan in 1982. Increase in poverty as well as the widespread dealing of crack, which was easier to access than powdered cocaine, meant an increase in incarceration rates of low income people of color as well. Significantly, crack and cocaine are identical in molecular composition; however, crack had become associated with blackness and thus a worse form than powdered cocaine, which was used just as frequently by high-income white people as a “party drug.” More so, crack was cheaper to produce and therefore circulated more easily among lower income communities as opposed to cocaine which was mostly circulated and in the possession of middle and upper classes, and more specifically, white people. A study conducted by the ACLU found that “in 1986, before the enactment of the federal mandatory minimum sentencing for crack cocaine offenses, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 11% higher than for whites. Four years later, the average federal drug sentence for African Americans was 49% higher.”

“What Raegan eventually does is takes the problem of economic inequality, of hyper-segregation in America’s cities, and the problem of drug abuse and criminalizes all of that in the form of the war on drugs,” argues Ava Duvernay in her documentary 13th.

This narrative was only furthered by President Bill Clinton who proposed several policies encouraging policing and the death penalty for violent crimes. During his administration, the three strikes rule for prisoners as well as mandatory minimums were created. This meant that cases moved from under the jurisdiction of judges to that of prosecutors; notably, 95% of elected prosecutors throughout the U.S. are white. “Truth in sentencing,” which is a law enacted in order to reduce the likelihood of early release from imprisonment, has often been questioned as a result of this change in how individuals charged with crimes get prosecuted and sentenced. Significantly, 97% of those locked up, for example, have plea bargains and do not even go through trials. This was significant to the Clinton administration as he claimed a more hardline approach with regards to criminal justice in order to gain support and win the presidential elections.

Under Bill Clinton, sixty new capital offense punishments were also added to the law, and the 1994 Federal Crime Bill led to the massive expansion of the prison system through increase in funding and personnel such as police officers. This bill then also meant the expansion of the prison industrial complex, and hence the benefit of certain corporations as well as the political progression of Clinton through similar means to Raegan and Nixon.

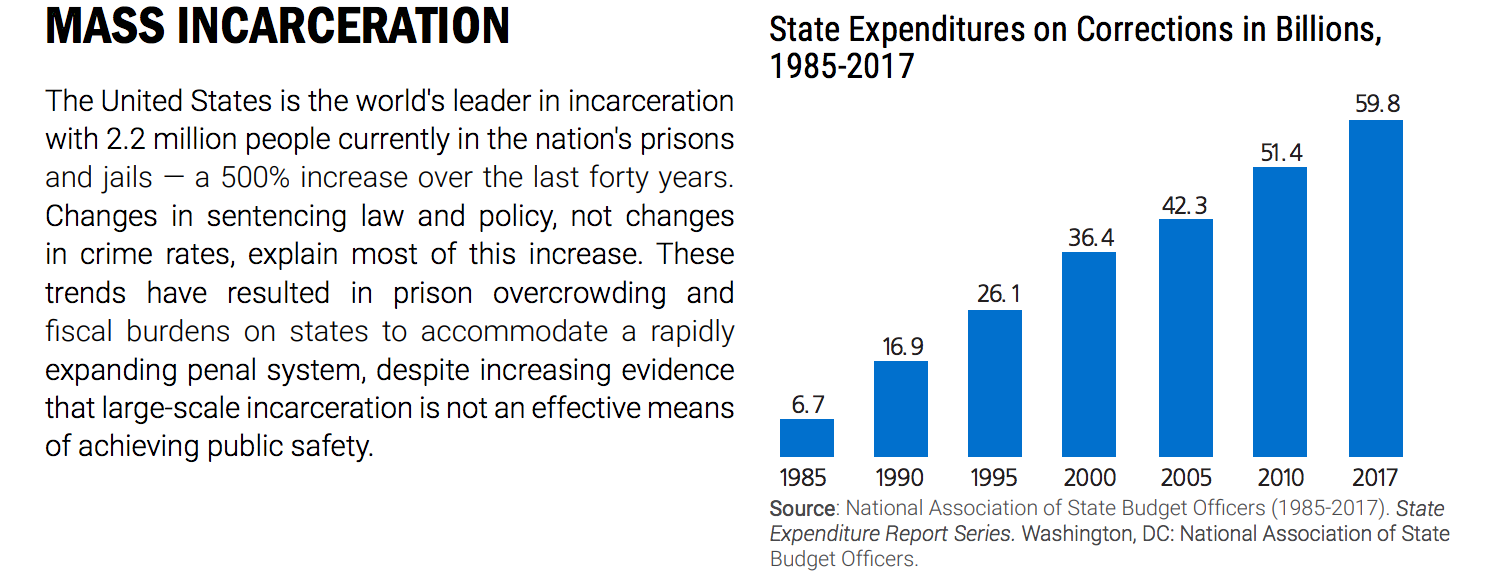

As seen in the figure above, extracted from The Sentencing Project: Fact Sheet: “Trends in U.S. Corrections,” state expenditure on corrections has dramatically increased over time. This attests to the use of mass incarceration as a political strategy that perpetuates racial discrimination as politicians have increasingly utilized a hardline criminal justice approach in order to gain public support. This is especially evident with the election of Clinton and the expansion of the prison system which included increase in funding.

It also asserts the influence of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) on policy bills. ALEC is a lobbyist group that advocates for limited governance, free markets, and federalism. Importantly, ALEC claims the membership of many organizations and legislators. Previous member, Correction Corporations of America (CCA), has benefited as the leader of private prisons as a result of such influence over federal spending. The CCA has had a role in shaping crime policy across the country, including the increase in criminalization of communities of people of color. More so, there is now a move towards the privatization of probation and parole by the American Bail Coalition, a system in which people could be incarcerated within their own communities.

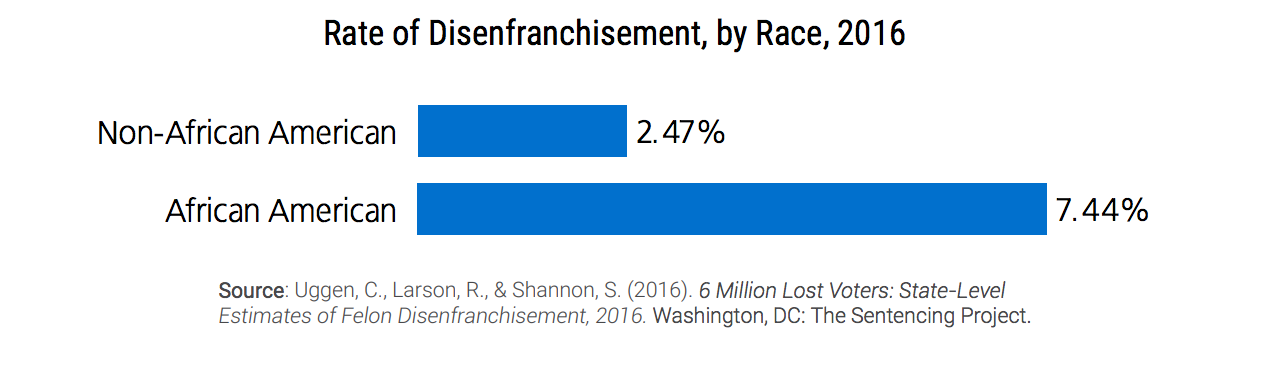

In prison, incarcerated individuals experience a process of immediate sensory deprivation and dehumanization, followed by disenfranchisement that essentially removes their rights as citizens, such as the right to vote or get a job as the right to vote excludes previously incarcerated people. The racial caste then seen during the Jim Crow era has been redesigned. Not only has there been incessant criminalization and disenfranchisement of black people, but convict leasing has also risen as a new form of slavery. Convict leasing, which started as early as 1844 in Louisiana, means the leasing of the labor of those incarcerated, often without compensation and in poor conditions, in order to increase profit in a certain sector. The legal inheritances from times of slavery in the United States have become the foundations for the modern prison industrial complex, in which black men make up 40.2 per cent of the prison population while only making up approximately 6.5 percent of the U.S. population.

The above chart is from The Sentencing Project: Fact Sheet: “Trends in U.S. Corrections”

Ta-Nehisi Coates deems reparations to the black community a question of citizenship. When the history of mass incarceration is looked at with the recognition that members of colored communities have consistently been treated as second class citizens, this is undeniable. Coates makes the claim that slavery and past plundering cannot be separated from today’s context of mass incarceration and the “logic of enslavement respects no such borders.” This enslavement which overarches over private and public spheres presses the question: how should the U.S. go about institutional reform when politicians and corporations have weaponized racial discrimination in veiled lines to gain political prowess? Could an unofficial form of truth-telling and truth-seeking place the pressure necessary for institutional reform and justice? Questions of employing transitional justice mechanisms such as truth commissions and reparations in a consolidated democracy then suggest a new approach to these mechanisms to encourage institutional reform. Political strategies have begun to shift and so we must ask “do we feel comfortable with people taking a lead on a conversation in a moment where it feels right politically?”

What the Democratic Candidates Say

With that in mind, as well as the events of the recent presidential debate in New Hampshire, it’s important to note the political stances of the democratic presidential candidates to ask of the intentions and the applicability of criminal justice policies and policies on mass incarceration. The Marshall Project outlines the stances of these candidates.

Significant to this discourse is the recognition that all democratic presidential candidates oppose the death penalty. Bernie Sanders and Peter Buttigieg would like to eliminate mandatory minimums while Elizabeth Warren and Joe Biden would prefer reducing them. All candidates would like to legalize marijuana while Biden would vote on decriminalizing it instead. Likewise, Sanders believes that those incarcerated should have the right to vote while Biden, Buttigieg, and Warren believe that those incarcerated should only have the right to vote when they have left prison.

Other topics to consider include the reform of the bail system, use of clemency, and use of private prisons at a federal level. With these stances noted, one must contextualize and recognize how such policies would affect the communities of those most implicated as a result of the systemic racism in place. One must also question why there hasn’t been more discourse on reparations for the years of weaponized racial discrimination that have been enacted through the prison industrial complex and the mass incarceration of people of color.