by Genevieve Zingg, a blog writer for RightsViews and a M.A. student in Human Rights Studies at Columbia University

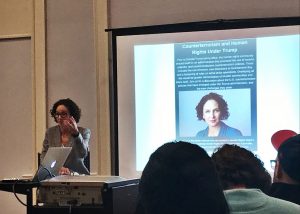

On Monday, the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School hosted an event on counterterrorism and human rights under the Trump administration. The event featured Laura Pitter, senior national security counsel at the United States program of Human Rights Watch, speaking on the new human rights challenges posed by counterterrorism policies emerging under President Trump.

Prior to working with HRW, Pitter was a journalist and lawyer with the U.N. in Bosnia and Afghanistan. Under the Obama administration, she worked on accountability for past instances of torture and the prevention of government-sanctioned torture. Specifically, she worked to document torture that had not yet come to light prior to the Senate Intelligence Committee report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation program.

Human rights concerns under the Obama administration centered on detention practices at Guantanamo and the use of drone strikes. During this time, HRW focused on encouraging the release of Guantanamo detainees and ending the military justice system it operates under. There was also concern under Obama about the overly broad use of terrorism prosecutions, which were used to target individuals who did not necessarily express any intent to engage in terrorism.

Once Trump was elected, HRW’s focus changed as the administration explored the use of torture becoming a legal part of official policy and loosened rules for drone strike operations overseas. “There was already a lack of transparency with regard to drone strikes under Obama’s policies,” Pitter explained during the event. “They said they were careful, but civilians were killed, and we know that they did not properly investigate strikes that went wrong, follow through with reporting requirements, or pay condolence compensation.”

The rules under Obama were already loose, and the concern is that they will continue to deteriorate under the Trump administration. For example, Trump is considering giving the CIA more control over strike operations, so they would be even less transparent than they already are. As a result, Pitter said her work has become more domestically focused under the Trump administration. Trump’s “clear expression of hostility towards Islam” and policies directed toward “radical Islamic terrorism” are a matter of significant concern to HRW, she explained, especially once a draft executive order authorizing the reopening of CIA “blacksite” prisons was leaked in January 2017.

Further concerns over close U.S. partnerships with forces carrying out human rights abuses remain, namely focused on UAE and Saudi partners in Yemen. “We’re worried about proxy detentions and proxy interrogations,” Pitter said. The U.S., for example, has interrogated people in facilities in Yemen where there have been documented cases of torture by the UAE and Saudis. The U.S. claims to not know about these cases, according to HRW. When the organization released its report detailing the U.S.’s use of these facilities in Yemen, Senators John McCain and Jack Reed sent a letter to Defense Secretary James Mattis asking for an investigation. The explanation they received is currently classified, but HRW is advocating to have it made public.

“One thing we’re doing more of now is pressing other governments to press the U.S.” Pitter said, responding to a question during the event. “In order for the U.S. to carry out its work abroad, particularly in foreign policy and military operations, it requires the cooperation of other governments. HRW has always had a strong U.N. team, but we operate in that forum more aggressively now.” For instance, HRW built strong alliances with countries like Canada and the Netherlands to push the U.N. Human Rights Council to establish an international inquiry on war crimes in Yemen, against Saudi objections.

The talk emphasized that part of the frustration of the human rights community is that many of the policies laid out by the Obama administration have expanded and are being more aggressively enforced, including large-scale surveillance by the FBI of Muslim communities and immigration deportations. As for the Muslim Ban, arguably Trump’s most controversial executive order at this point in his presidency, there is a larger role for the courts to play in protecting human rights. “The courts from Hawaii to Maryland have recognized that counterterrorism is not a justification for the ban. Even Homeland Security has said that country of citizenship is not a reliable indicator of terrorist activity,” Pitter said. “The government can carry out counterterrorism initiatives without violating the rights of a specific religious or ethnic group. Policies like the Muslim Ban are actually counter to security because they generate anger and hostility toward the U.S.”

There has been strong pushback from the Departments of Defense and Justice and the State Department against some of Trump’s controversial security policies. The DOD and DOJ, for instance, have pushed back against expanding Guantanamo, which currently holds 41 people, only 7 of whom have been charged, while the DOJ has pushed for the use of federal prosecution over military commissions. The CIA and State Department, likewise, have also warned against the floated policy proposal to designate the Muslim Brotherhood a terrorist organization, arguing that it doesn’t make sense from a foreign policy perspective.

Pitter ended her talk by focusing on the positive. “This administration has emboldened voices that were silent before. The administration has legitimized discrimination and animus toward minority groups, but at the same time, this has mobilized the human rights movement and engaged communities that weren’t engaged before,” she said. “It’s both a threat and an opportunity to promote respect for human rights, due process, and the fairness of the justice system.”

Genevieve Zingg is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in Human Rights Studies at Columbia University, focusing on human rights in the context of armed conflict, counterterrorism and national security. She is interested in refugees and migration, foreign policy and international politics, international criminal and humanitarian law, and intersectional issues of race and gender. She holds a B.A. (Hons.) from the University of Toronto and has professional experience working in Geneva, Athens, Paris, Brussels and Toronto. Connect with her on Twitter @GenZingg. She is a blog writer for RightsViews.