By Daniel Golebiewski, graduate student of human rights at Columbia University

___________________________________________________________________________

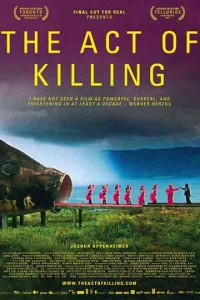

On March 8, 2014, Columbia’s School of the Arts, in collaboration with the Institute for the Study of Human Rights (ISHR), screened Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 documentary, The Act of Killing. This film was shortlisted for a 2014 Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary. On this evening, the audience had the chance to see the Director’s Cut and ask Oppenheimer questions regarding trauma, memory, and the power of filmmaking.

In 1965, Anwar Congo and Adi Zulkadry—Indonesian “gangsters” deriving their label from the English “free men” meaning to live on without punishment from the criminal justice system—accepted their role as leaders of the most well known killing squad in North Sumatra. In The Act of Killing, Oppenheimer invites these two gangsters and their comrades to reenact their assassinations of Chinese communists. They seem eager to create a film that uses humor and romance, as well as inspiration from their favorite movie genres like Westerns and musicals. In fact, they decide that they want to create more sadistic scenes than those that can be found in movies about Nazis, as well as more action scenes than those typical of James Bond films. Despite these disconnected intentions, the documentary effectively puts forth three important themes: the effects of trauma, the importance of memory, and the power of filmmaking.

Unlike his comrades, Anwar—the main executioner—fails to hide his pain. Although he dances the cha-cha, drinks alcohol, smokes marijuana, or dresses to impress, when it comes time for him to play a victim, he breaks down. He says that he feels what his victims must have felt and describes feeling as if he “were dead for a moment.” Although Oppenheimer points out that the victims’ torture was much worse because they knew that they were going die, Anwar tearfully says that he does not want the memories of what he did to come back to him. In fact, when he revisits the rooftop where he claims many of his killings took place, Anwar gags repeatedly and then asks himself, “Why did I have to kill them? I had to kill… My conscience told me that they had to be killed.” His memories continue to haunt him during a reenactment of a burning village. Never expecting the scene would look so awful, he believes his victims have “curse[d] [him] for the rest of [his life],” meaning karma will come back to haunt him, whether during this lifetime or in his dreams. Anwar faces nightmares. He dreams about repeating his invented, simple method of wrapping a wire around his victim’s neck and pulling the wire from one end, suffocating the victim without a “bloody mess.” By using this method to kill almost 1,000 people, Anwar repeatedly dreams that he meets the ghosts of his victims face-to-face.

Oppenheimer wished to create a film that would force the Indonesian perpetrators to acknowledge that they killed thousands of communists, crimes for which they have not been held accountable. Thus, by allowing them to reenact their crimes in the manner and style in which they remember them, unlike a historical narrative, Oppenheimer tried to make “a documentary of imagination.” In other words, the film tries to blur the usual good vs. evil narrative often seen in this genre. As a result, the audience gets the chance to understand the perpetrators; in this case, Anwar is not solely a “killing machine” but has the capacity to repent for his past atrocities. Hence, the film argues that humans are complex and difficult to understand—Anwar appears proud to have been involved in events that have defined Indonesia but, at the same time, becomes ashamed when the victims’ families confront his actions. As Oppenheimer noted during the discussion, we all have a link to the perpetrators; in this case, when we buy products made from Indonesian palm oil, part of the cost goes to the Indonesian perpetrators, many having positions within the Indonesian government.

Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing attempts to bring the Indonesian genocide to light through the reenactments of the former anti-communist perpetrators. Although Anwar shows signs of trauma, he and the gangsters continue to live as “free men,” or as one of them says, a life of “relax and Rolex.” Moreover, these gangsters believe that although they strangled their victims with a wire, they “were allowed to do it” and “the proof is [they] murdered people and were never punished.” In fact, for the people killed, they say, “there’s nothing to be done about it” and the victims “have to accept it.” As a result, many “never felt guilty, never been depressed, never had nightmares.”

One can only hope that The Act of Killing influences the Indonesian government and the international community to hold these “free men,” “gangsters,” “perpetrators,” or whatever else they call themselves, accountable for war crimes.

Daniel Golebiewski is a graduate student at Columbia University where he is pursuing a Master of Arts in Human Rights Studies. His interests are transitional justice and memory through the arts.

An excellent movie but here ago “man’s inhumanity to man ” shows the evil that lurks in man’s heart. Give them an excuse and permission he will do the most vilest things to his fellow man. If anything they should have deported the communists etc and not murder the,. Indonesia continues to be a a country that many many people, from other countries, are very wary of and so they should be. Criminals run it and have done so for over 40 years.