Upon completing this module, you will be able to:

- Identify teaching assumptions that may inhibit student participation.

- Differentiate between receptive and generative modes of student engagement.

- Generate methods by which instructors can transition between teaching modes.

- Implement three in-class techniques by which students can comfortably begin to take ownership of learning material.

Students are infrequently the in-class interlocutors we hope they will be. As educators, we can all likely recall moments when the lack of student engagement made us doubt either our students or ourselves. Consider the following reflection by a TA in the Religion Department:

I can vividly remember my first few times leading discussion sections for Michael Como’s Introduction to East Asian Buddhism, where I would ask my students what I was sure were interesting and important questions only to be met with uncomfortable silence. I am sure we are all familiar, or at some point will become familiar, with that silence; a silence that we fill – or at least I filled – with doubts about my abilities to teach: “What am I doing wrong? Why aren’t my students engaged? Am I a bad teacher?”

Yet there is an important distinction between a lack of in-class participation and a lack of student willingness to engage, just as there is a distinction between unresponsive students and our capabilities as instructors.

This teaching module, adapted from Joe Fisher’s 2019 CTL workshop of the same name, will provide you with tools to help you overcome situations such as this one. Each of the strategies you will encounter is a method of helping students transition from passive listeners or recorders of information to active participants in the generation of class knowledge. It is the success or failure of this transition, from instructor-directed work to student-initiated activity, which accounts for much of our ability to activate student engagement.

Identifying Assumptions

The first step in activating student engagement is to reflect on past situations during which our expectations for student participation were not met. What happened (or did not happen)? What did you expect to happen? What assumptions undergirded your expectations? It is only after considering the assumptions which may have led to our unmet expectations that we can deliberately pursue teaching strategies with a higher chance of success.

Identifying assumptions can be challenging. Luckily, there are resources available to help. Stephen Brookfield (1995) describes four lenses through which to identify teaching assumptions, namely, students’ eyes, colleagues’ perceptions, personal experiences, and theoretical scholarship (8). These lenses can be concrete: the CTL can help you solicit feedback from your students or peers. These lenses can also be speculative: “stepping into the shoes” of our students or peers can provide new insights about effective teaching.

Consider the subsequent reflection by the same Religion Department TA:

I had made a number of faulty assumptions: that students would be motivated to discuss the class material even though they spent the vast majority of their time in class as passive listeners and recorders; that they were equipped to organize and express their thoughts in ways appropriate for academic discourse; and that questions inherently motivated response. Maybe I made these assumptions because I had seen it work before or because I was imagining myself in the position of the student – after all, I was (and still am) a student too. Regardless, I knew that I would need to find other methods for activating student engagement moving forward.

The assumptions this TA held about his students’ preparedness for participation on his terms proved faulty. His reflection allows us to benefit from three takeaways:

- The transition from receiving and recording class material to generating and discussing that material can be challenging.

- It cannot be taken for granted that students are able to understand and fulfill the expectations of academic discourse.

- Questions do not inherently motivate student responses.

Reflection Exercise

Before reading onward, reflect on a personal teaching moment during which student engagement failed to meet your expectations. Using one or more of Brookfield’s lenses, consider: what assumptions may have inhibited the success of this teaching moment? What did those assumptions prevent you from recognizing?

Accessibility

Recall the three takeaways from our former TA’s reflection:

- The transition from receiving and recording class material to generating and discussing that material can be challenging.

- It cannot be taken for granted that students are able to understand and fulfill the expectations of academic discourse.

- Questions do not inherently motivate student responses.

These three points underscore the need for instructors to scaffold in-class activities so that students feel prepared to engage in new modes of learning. In other words, student engagement depends upon accessibility. Although accessibility is a multifaceted topic that exceeds the scope of this teaching module, the abovementioned takeaways underscore the importance of two facets of accessible classrooms: graduated levels of support for building fluency and salient goals and objectives.

Modes of Student Engagement

Especially in lecture courses, much of in-class student engagement involves listening and taking notes; in other words, students receive and record information. By contrast, when instructors seek to assess the quality of student participation in class, they most often do so by soliciting paraphrases, comments, opinions, and/or questions from students; that is, they request that students switch from a receptive mode of engagement to a generative mode.

Presuming that students know how to make that switch to your satisfaction can lead to mutual resentment in the long term and awkward in-class exchanges in the short term. In order to help students make the switch, instructors should clearly identify when and in what terms you expect students to switch from a receptive to a generative mode of participation.

The Power of Play

The above recommendation to set rules for student participation might seem domineering or antithetical to the creative thinking and free expression you hope to foster in the classroom. Yet when seen from the perspective of play, the inauguration of a temporary set of rules and expectations – i.e., declaring a game – can be a liberating condition for students. Mark Leather, Nevin Harper, and Patricia Obee (2020) advocate for the implementation of “play” within postsecondary education as a way to empower students to engage class materials creatively:

We consider playfulness to be a mixture of an openness to not being self-important, to playing the fool, not worrying about competence, not taking social norms as sacred, and finding ambiguity and double meanings as a source of knowledge and pleasure (6).

Declaring a game – a time-bound, rule-bound activity set apart from routine class time – performs the task of transitioning students from receptive to generative modes of engagement insofar as it amounts to a class-wide mode switch. It resolves what can otherwise seem to be ambiguous expectations for “proper” engagement, since the rules will be made explicit. It thereby enables students to adopt an attitude of playfulness.

From Theory to Practice

The following three activities are “games” that explicitly position students in situations to engage with course materials in different ways. In the words of Joe Fisher:

All three of these activities encourage students to take ownership of the material, to think through and express it in terms accessible to them. When students are encouraged to translate ideas rather than just record or memorize them, not only are they much more likely to retain the relevant information but they are also likely to continue to try to expand on and complicate those ideas…. By believing that their own thinking is relevant, students, in turn, gain incentive to be more engaged.

In-class Writing: The Conversation Template

The following exercise was developed by Joe Fisher during his appointment in the Undergraduate Writing Program. The Conversation Template was Joe’s solution to engage students with class materials while remaining true to the primary learning objectives of the course – developing writing proficiency. He challenges us to think of in-class engagement differently, since writing is not only the expression of knowledge but also a means of knowledge generation. Just as much as peer-to-peer conversation, then, in-class writing affords students opportunities to formulate and articulate responses to class materials.

In order to facilitate engagement via writing among students from data science backgrounds largely unfamiliar with composing academic prose, Joe relied on writing templates, based off of the work of Graff and Birkenstein (2010). According to Joe:

Templates provide different fill-in-the blank sentence and paragraph structures students can use to organize their thoughts for the purpose of summarizing and synthesizing ideas, generating problems or claims, introducing evidence and examples, and so forth. More than just how to write, templates can push students to dwell with particular lines of inquiry – what is the author’s main claim? How does the author support their argument? How would another one of our authors respond to this argument? – and to structure their thoughts in ways appropriate for academic discourse at the sentence and paragraph level.

To use templates, then, helps students transition from the encounter with course material to an engagement with it (cf. SHOLT module 3). As discussed previously, scaffolding this transition into engagement is an important step in empowering students to take ownership over their learning experiences.

Joe authored two worksheets for students to use at different stages in his course:

I-Say-Template – these three sentence templates – signaling agreement, disagreement, and complication – are provided to students after each reading in order to force them to identify and dwell with the aspects of the text that are most relevant to them. Here students are given the flexibility to choose and complete one from each list.

The-Conversation-Template – this handout is provided after students have read multiple texts and begun to think through their essays. Here they are asked to fill out an entire paragraph template that synthesizes the conversation they want to generate and disrupt.

Reflection Exercise

Open and complete the “I Say” template, using this course module as the text to which you respond.

After you fill it out, consider how you might apply a worksheet such as this in your own course. How would you introduce this worksheet to your students? How would you subsequently have them reflect on this worksheet?

Peer-to-peer Learning: The Jigsaw

The following exercise was introduced to Zach Domach by a peer during his time as a teaching consultant at the CTL. Zach found the activity particularly useful in the classroom insofar as it “encourages close reading, places students in the role of the ‘expert’ — thus granting them more autonomy and agency — and covers more of the text than is possible with other sorts of activities.”

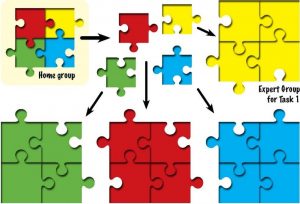

In brief, “the Jigsaw” is a small-group exercise during which members of breakout groups are tasked to become “experts” of a small portion of course material. Each small group is assigned different material to master. After an allotted time, students form new groups so that each group contains at least one “expert” of each piece of course material. Then, students are tasked to teach one another their respective areas of expertise.

Consider the following diagram of “the Jigsaw” taken from a worksheet passed down to Zach from his peers at the CTL:

Example

Suppose, for example, you led a recitation section of twenty students. In the space of a one-hour recitation section, you could implement “the Jigsaw” in order to have students review four articles assigned for the previous lecture course. The exercise could run as follows:

- (~1-5 minutes) Create groups of four students. Since you have four articles, perhaps ask them to “count off” from one to four. In this example, you will have five groups of four students.

- (~1-5 minutes) Assign each group a different article to “master.” Since you assigned four articles but have five groups, two will be mastering the same material. Instruct your students to review their assigned article based on whatever criteria you choose. Note that students will be more effective in their small groups if you provide them a rubric (perhaps even a worksheet) according to which they can engage with the articles.

- (~20 minutes) Allow each group to review its assigned article.

- (~5 minutes) Ask students to finish their review. Next, have students in each group number themselves from one to four. Form new groups based on this numbering. You will now have four groups of five students, and each group will contain at least one “expert” of each article.

- (~20 minutes) Task members of these newly formed groups to teach one another their respective areas of expertise. If necessary, monitor groups to ensure that each member is afforded the opportunity to share. Again, the exercise will be more effective if you provide a template for the information you expect students to cover during this time.

- (~5 minutes) Wrap up.

Note: This exercise is prone to being noisy.

Reflection Exercise

In the context of a class you currently instruct (as a TA or otherwise), think of how you might utilize “the Jigsaw” to cover course materials. How would you divide course content into segments that you could apportion to small groups? What rubrics for expertise would you provide students so that they could master course content in small groups? What template would you provide so that students could synthesize what they learned from other “experts”?

Translating Terminology: “Skillful Means”

Quinn Clark has found the use of analogies useful when explaining difficult terms or concepts to students. Moreover, he has found that when grounding explanations in terms familiar to those of different academic disciplines, translation work can be an excellent way of establishing rapport with students. Naming this analogical method of teaching “skillful means” after a concept taught in Michael Como’s East Asian Buddhism course, Quinn explains its merits as follows:

The use of analogy implies that something is going to be lost in translation, and as graduate students, many of us obsess over complexity, “problematizing,” and imperfect generalizations. As specialists, we are trained to believe that “good enough” is not good enough, and that it’s bad or potentially dangerous to paint in broad strokes. As instructors or TAs teaching non-specialists, however, we have to meet students halfway.

When assigned to Michael Como’s East Asian Buddhism, students learn about “skillful means” – the Buddha’s heuristic teaching method by which insistence on the “Truth” is subordinated to conveying the “truth” that a given student is capable of understanding at the time. For students who do not speak English as a first language, have never taken a Humanities course before, or are first-generation college goers, the meaning, significance, or coherence of technical terms may not be immediately accessible. Employing “skillful means” may be the most expedient method for instructors who hope to enable intro-level students to grasp new conceptual material.

One thing that I find helpful is learning something – anything – about a student, such as their major, where they’re from, or a hobby or interest. This gives me a chance to explain a troubling or difficult concept in terms of something with which they are already familiar.

Quinn is candid about the limits of analogies to capture the historical complexities of course materials, but defends the analogical process as one that makes initial encounters with complicated topics more successful for students of varying backgrounds. His success with “skillful means,” however, stems from his familiarity with his students.

Reflection Exercise 1

Consider a course you are currently teaching, whether as a TA or otherwise. Now make two lists: first, compile a list of your students and their majors. How familiar were you with the range of disciplines represented in your class? Second, make a list of key terms for your course. Which are most challenging for students?

Example 1

Quinn reports that, during his time TAing for Michael Como’s East Asian Buddhism course, many students struggled with the concept of “karma” because they relied on pop cultural understandings of it or because they associated it with one religious tradition and not another. One day, a student came to his office hours with these kinds of complaints and questions. While exchanging pleasantries at the beginning of their meeting, Quinn learned that his student was a physics major. In an effort to levy this student’s background in Physics, Quinn suggested that he could think about karma as the early Indic “atom”:

Everything is made up of it, even though the world before us doesn’t appear so. At the time of the Buddha, nobody “believed in karma” or didn’t, just as nobody today “believes in atoms.” This is a given in our time and place. What makes different religious traditions distinct are their various “atomic theories” – that is, how they conceive of karma and its operations, its nature, its ultimate source, and the possibilities for its manipulation by humans. Yogis and tantra practitioners are specialists because they attempt to figure out how to “split atoms” (manipulate karma) in order to fly or heal illnesses, just as contemporary physicists try to understand how to split actual atoms with various results.

This student then asked, “if karma was some kind of Buddhist atomic theory, why were Buddhists so interested in “the self,” and why did they reject karma? Particle physicists don’t talk about the self, psychologists do, right?” Quinn responded:

The Buddha didn’t reject the concept of karma, but he tried to make the radical claim that the only things holding a karmic “atom” together are the centrifugal forces of subatomic parts whizzing around, which gives the impression of a stable object even though, as we all know, in the case of atoms, it is an illusion. Just as there is no core at the subatomic level – just little pieces spinning around – so too, the Buddha claimed that there is no permanent, unchanging, little “you” at the subatomic karmic level.

Example 2

Although this scenario worked well for Quinn and his student, it is far from the only way to apply analogical thinking in classroom settings. Consider, for example, a “think, pair, share” activity wherein students are tasked with creating rough analogies for course terms based on key terms in their own majors (e.g. “priests are like mitochondria,” or “ritual is like the scientific method…”). After 5-10 minutes of individual reflection, you could pair students together so that they can challenge and expand each other’s analogies. After another 5-10 minutes, you could pull the whole class together and ask for volunteers to share exemplary analogies of class terms.

Note: Few such analogies will be perfect fits – that is part of the challenge and reward of the exercise. Your role as instructor should be to indicate notes of dissonance, but also to acknowledge what works.

Reflection Exercise 2

Having reflected on your list of student majors and class terms, pick a term and a major at random. Now test out the analogy exercise in example two. Based on your experience with the task of thinking analogically, how might you employ “skillful means” in your classroom?

Thank you for reading!

By checking our assumptions, acknowledging different modes of student engagement, and pursuing occasions for play, we can foster classrooms wherein students can begin to take ownership of their learning process as engaged participants in course materials. Yet the three activities outlined in this module are far from the only three.

Feedback

As you test various methods of activating student engagement in your own classrooms, please share your experiences — successes, failures, and takeaways — in the comments section below.

Satisfied or frustrated with this resource? Please leave your comments below.

Further Reading

Brookfield, Stephen. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995.

Graff, Gerald and Cathy Birkenstein. “They say, I say” : the moves that matter in academic writing. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2018.

Leather, Mark, Nevin Harper, and Patricia Obee. “A Pedagogy of Play: Reasons to be Playful in Postsecondary Education.” Journal of Experiential Education, 2020.

Newby, D. R. “Opportunities and precarities of active learning approaches for graduate student instructors.” In Teaching Gradually: Practical Pedagogy for Graduate Students, by Graduate Students. Sterling, Va: Stylus Publishing, forthcoming Autumn 2021.