Welcome to the online supplement to TA training. These reference modules are meant to facilitate in-person training by the President and Vice-President of the Religion Department’s Graduate Student body for the benefit of second-year graduate students who are about to begin TA-ing.

The topics covered in these modules are not comprehensive, but rather include several topics that veteran graduate students have retrospectively identified as important for the quality of life of new TAs.

These include:

- Teaching tips

- Grading

- Managing difficult students

- Managing difficult professors

Not included among these lessons are the Rules and Responsibilities for Religion department TAs, which can instead be found here.

Similarly, tutorials on various online platforms central to TA work can be found on the main page of pedagogy.religion.

Recitation sections can be the most rewarding facet of your TA experience, and they can also be the most taxing or frustrating. Depending on your instructor’s guidance, you may have an itinerary to follow during these meetings with students. More often, however, you will be responsible for structuring recitation sections.

Common objectives for recitation sections include:

- The clarification of key concepts delivered in lectures

- The solicitation of student interpretations of course materials

- The resolution of student questions and doubts

Additional pursuits are also viable, such as:

- The development of relevant skills (close reading/analytical writing/argumentation, etc.)

- Peer-to-peer evaluation and feedback on assignments

The duration of recitation sessions rarely exceeds 50-60 minutes. Since these meetings are brief, it helps to have a plan in place: what would you like students to take away from a given session? Without a clear plan, you may find yourself in a scenario similar to this:

TA-X leads a recitation section of 12 students during a weekly 50-minute session. Six students sit around a conference table with TA-X, while six students sit in chairs that line the perimeter of the room. This week, TA-X begins the section meeting by recapitulating the professor’s lecture in ten minutes, concluding the recap by asking “what questions do you have?” For the next thirty minutes, punctuated by long silences, TA-X answers three or four questions asked by the same four students, all of whom sit at the table. When it seems that there are no forthcoming questions, TA-X asks students to turn to one of the course readings, and then reads aloud a key passage. TA-X then asks students, “what are the main takeaways from this passage?” For the next ten minutes, the same four students provide their interpretations of the passage. TA-X nods, affirms, and provides a final explanation of the relevance of the material. Then, seeing that the students in the room look tired, TA-X decides to end the meeting a few minutes early.

Undoubtedly, this section meeting could have gone better. Were you to give advice to TA-X, what suggestions would you provide about the following classroom dynamics:

- Time

- Space

- Student engagement

- Course materials

Here are a few suggestions that we have come up with. Feel free to try any of these in your recitation sections:

- Begin class with a five-minute writing prompt to kickstart subsequent conversation

- Invite as many students (by name) to the table as possible, and intentionally include students seated at the periphery in conversations/activities.

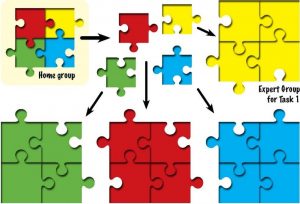

- Use small-group activities that allow students to converse with one another.

Further Reading:

Grading actually involves three steps: (1) evaluating student work, (2) providing feedback, and (3) assigning a grade. Although this labor will be time-consuming at first, there are strategies you can employ in order to transform grading from menial work into a rewarding engagement with the learning process of your students. We offer a few such strategies here. Note that your instructor may have standards for evaluation that differ from what is included below. Be sure to converse with your instructor about how you are expected to grade student work.

Rubrics and honest impressions:

Evaluating student work is ultimately a subjective process. Do not frustrate yourself by attempting to achieve a robotic level of evaluation. A thoroughly mechanical and “objective” approach may sound appealing because it offers a consistent method for deriving grades, but it will actually hinder you from generating meaningful feedback for your students. Additionally, such an approach is too time consuming. This is not to discredit strategies meant to ensure fairness or consistency when evaluating student work. To the contrary, anonymizing essays and using rubrics are effective methods to ensure that you maintain consistent standards when evaluating your students’ assignments.

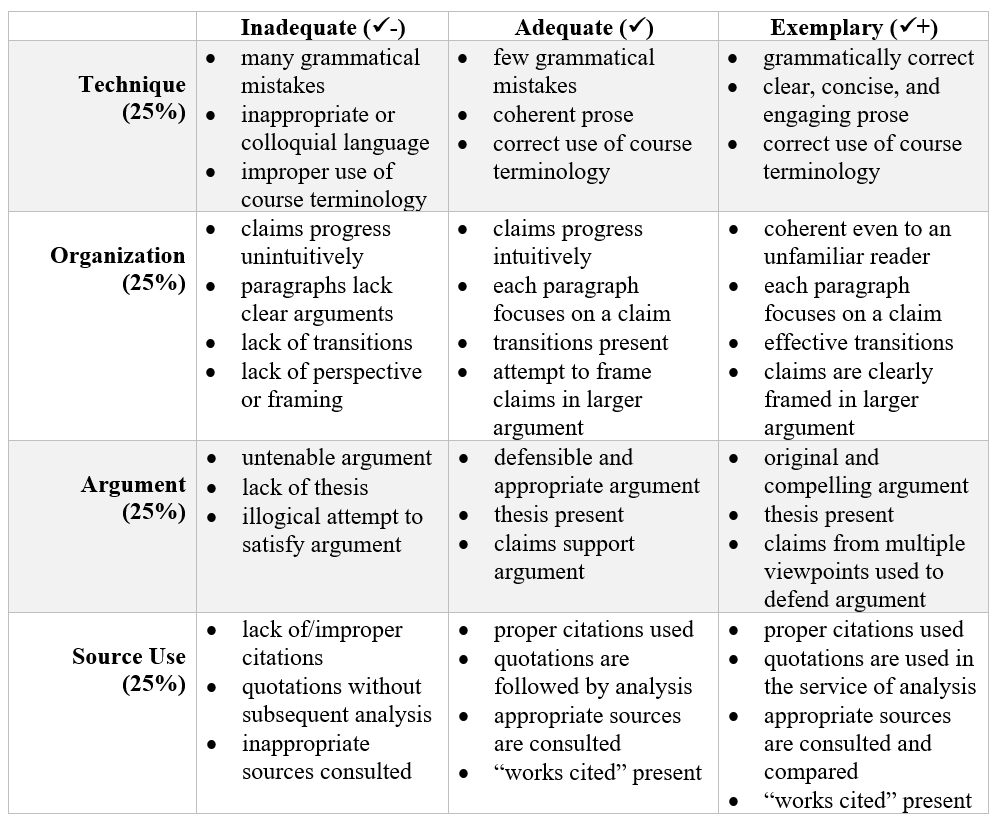

Consider the following “All Purpose Rubric” that we have put together in consultation with CTL resources. The metrics along the Y-axis help structure the grading process, but the metrics along the X-axis prevent the evaluative process from becoming too rigid:

Feel free to refer to this rubric when evaluating student work. Better still, share this with your students so that they have an idea of how they are being graded.

Feedback:

If grading makes you feel dead inside, it is likely because you are focusing on assigning letters and numbers instead of nurturing student growth through feedback. Despite what grade-grubbers may lead you to believe, students care about more than passing with an “A”. Your affirmations and critiques have an immense impact on students’ subsequent attitudes toward course materials, assignments, and themselves (to say nothing about their attitudes toward your performance as a TA, *cough, cough*). There are two main pieces to feedback: a summative note, provided at the end of a written assignment, and in-line comments and annotations.

A tried-and-true approach to providing meaningful feedback — especially when composing the summative note at the end of an assignment, is the “sandwich” method. Begin by acknowledging the success of an assignment, then offer constructive criticism, and end with an affirmation of the student’s efforts and learning progress.

What about in-line comments? Our recommendation is to annotate assignments in the same manner that you annotate a course reading: it should be a natural byproduct of your engagement with student work, rather than your evaluation itself. Save that for the summative comment at the end.

Grades and organization:

Most courses these days come equipped with a Canvas webpage, replete with a gradebook. This can be filtered by class sections, and it is well-worth your time to learn how to use the Canvas Gradebook effectively. We also recommend that you log student grades into an Excel spreadsheet. As redundant as it may feel to log grades into two systems, it will help to prevent you from mistakenly attributing the wrong grade to the wrong student, which unfailingly leads to confusion, bitterness, and a lot of wasted time.

Further Reading:

Students will make your TA experience rewarding. Students will make your TA experience insufferable. The difference is often a mismatch between a student’s motivations and your own. Below, we profile several types* of students who make TA work difficult, accompanied by our suggestions for how to manage them.

*The students described below are abstractions and do not refer to actual people. Often, the most difficult students fit more than one “type.”

The Creep:

Whether in office hours, in recitation, or even in lecture, this student gives you the heebie-jeebies. It could be eye contact, inappropriate comments, opinions, or attitudes, or a refusal to wear shoes — it could be nearly anything, but it still makes it difficult to share space with this student and is therefore a serious matter of concern.

- Share your discomfort with other TAs/the instructor

- Move the student into the section of another TA who isn’t similarly bothered.

- Confront the student about what bothers you.

- Hold office hours in public places, where you won’t be alone.

The Kiss-Ass:

This student wants to appear golden. From the perpetually raised hand to the refusal to leave class once it’s over, this student makes sure to be seen. Often this student is ingratiating to you or the instructor, reacts poorly to criticism, and behaves competitively with other students.

- Express and pursue your intention to call on a range of students

- Encourage the student to schedule office hours

- Affirm the student’s interest in course materials, and guide them toward additional self-study

The Mute:

This student is shy. Quite shy. Whether in lecture, in recitation, or even in office hours, this student refuses to talk.

- Speak with the student one-on-one about preferred modes of expression.

- (Reminder: you CANNOT ask students about learning disabilities — they must volunteer that information on their own)

- Assign group work with very small (two-person) teams

Further Reading:

Three types of headaches are common when managing difficult professors: those resulting from (1) unfair expectations, (2) differences of opinion, (3) unreachable professors.

In an effort to ensure healthy TA-instructor dynamics, Religion Department graduate students and faculty jointly authored a “Roles and Responsibilities” document that outlines what instructors can fairly expect from TAs, and vice-versa. We encourage TAs and instructors to review this document together at the beginning of the semester!

Likely, you will find yourself in a situation where your perception of how to address a task or problem differs from that of your instructor. Rather than defer to the instructor’s suggestions without question, it is important that you credit yourself and your perspective as worthy of consideration. Most faculty are very receptive to articulate and action-oriented suggestions. For this reason, we recommend that you communicate your suggestions about teaching-related tasks or problems in a confident and declarative manner, especially when using email.

Consider the following suggestion to a professor about problem X in course Y, delivered in the body of an email:

Dear Professor,

Several students have expressed confusion about the paper prompts you distributed last class. After rereading the prompts, I agree that the wording makes it difficult to identify just what you expect of students for the assignment.

I have taken the liberty of rewording the paper prompts myself, but I have not yet shared them with students. The new prompts are in the attached Word document, below. With your permission, I will forward these new prompts to the students.

Thanks,

TA X

We can’t guarantee that all such suggestions will win over the hearts of instructors, but we stand by the merit of an assertive tone when sharing your input.

With certain faculty, communication itself may be the issue. Consult with your peers in the department about how best to contact professors who are either rarely in-office or non-responsive via email.