By guest contributor Julie Uszpolewicz*

There is nothing as powerful in making the viewer realise the atrocity and the suffering of war, as an image. Statistics are too dehumanising, words leave too much to the imagination, but photography has the rare power of being apparently objective. However, looking at documented conflicts has been criticised by several post-modernist thinkers (such as Jean Baudillard) as being passive. In the contemporary world of social media, we are faced with images of horror more than we have ever been before, therefore, perhaps the question of the role of photography requires revisiting. Is there a right way to look at the war in the reality that is saturated with photographs of distant conflicts and human rights abuses? Perhaps this article will raise more doubts than give answers, but it seems worthwhile to stop for a second and ask what kind of pictures we are bombarded within the news.

The question of ethics in political photography is nothing new. We can recall the notorious debate over Kevin Carter’s “The Struggling Girl,” which won him a Pulitzer Prize, but for which he was widely criticised with remarks that he chose to take a picture instead of helping the famine victim. In reality, he was surrounded by soldiers and ordered not to interfere with the situation, but this

scenario still challenges the way we think about documenting atrocities. Is the objective of raising awareness about suffering enough to justify sending photographers to regions facing humanitarian disasters? There is a difference between artistic photographs of suffering that are then exhibited and lauded and the photographs that accompany journal articles that we see respected publications. Political photography appears in different contexts and for different purposes.

“These dead are supremely uninterested in the living.” This is how Susan Sontag’s essay “Regarding the Pain of Others” ends. She is right. Our awareness of the famine in Central Africa or of the atrocities in Syria is usually passive. Sure, we can feel sympathy for the suffering, we may even feel outraged or shocked or reflect on our own privileged position. But what is this sentiment for, if it has no real effect on the situation? The passivity of the spectator’s guilt is the argument most often put forward by post-modernist critics. “The true witness is that who does not want to witness,” writes Rancière in “The Emancipated Spectator.” When we open a photo documentary or even an article reporting the abuses of human rights somewhere we are already prepared for what we are about to see, we know to expect — it may still move us, but we make a conscious choice to look at it. However, Rancière was writing before social media became such an important channel for social movements and political manifestos. We may be scrolling through our friends’ stories on Instagram and see a video from the bombing of Aleppo or arrests during mass demonstrations — do we become any truer witnesses when we stumble upon those randomly or do we become desensitised as we quickly swipe to see a picture of an influencer having brunch in Soho?

The context in which a work appears is significant. The beauty of an image lays in its universality — the power that it holds outside of the circumstances in which it was created. This is why up to this day there is something unique in visiting the Last Supper or the Sistine Chapel. Political documentaries, though, can be cursed by this universality, by this detachment. Most contemporary conflicts take place in Asia or Latin America — in other words, for the Western viewer, they are, indeed, far-away situations with little effect on our daily lives. But even when things were happening much closer to the imagined border of the Western world like the European Refugee Crisis the media despite the overflow of photographs managed to distance ourselves from it. When you read a news article from the safety of your own home it not only shocks you or evokes sympathy, it also reassures you that you are safe. A photograph transported across contexts creates an uncrossable gap between the seeing and the seen.

“When we open a photo documentary or even an article reporting the abuses of human rights somewhere we are already prepared for what we are about to see, we know to expect — it may still move us, but we make a conscious choice to look at it.”

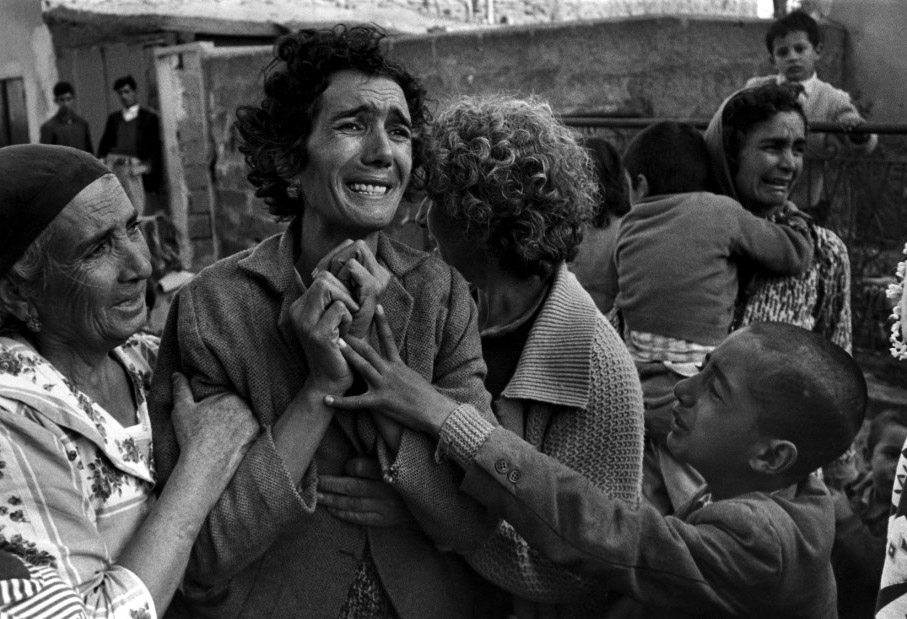

So, what role exactly do photographs play in illustrating the political situation? The awareness of death happening somewhere on Earth. Jean Baudrillard takes this argument further and claims that it is not a real death we are moved by when looking at pictures of casualties, but by their virtual death; the suffering depicted is so distant from us and so anonymous that it does not have the same effect on us as the real, tangible pain of someone closer to us. The objects of these photographs seem almost like fictional characters to us. Their suffering moves us on the intellectual, but not emotional level. This virtual death begs another question — the suffering of who exactly are we looking at? The victims of war become objects of a picture in the name of raising awareness, of sharing information. Photography objectifies. The captions of such documents are often anonymous — a suffering women, a scared girl or, simply, a time and a place. There are no names; they are just depictions of the general, mass victims of atrocities. Even in close-up portraits are just selected parts of some bigger crime against humanity. As much as photography is a medium often

perceived as objective it offers us only limited knowledge about the situation. After all, those images rarely give us any information we did not know before — do we really need to look at war documentation to become aware that terrible things do happen?

The underlying theme of all these analyses is searching for an answer to the question of why we photograph war at all. There is the shock factor — artists that are looking to evoke a strong emotional reaction in their audiences may gravitate towards suffering inflicted by conflicts to confront the brutality and cruelness of the world. However, this relates to news photography only to a small extent. Shocking images can be attention-grabbing — a characteristic strongly valued in a space dominated by social media. Any photograph of suffering is doubtlessly looking to awake sentiment, but the spectators’ guilt does not have any impact on the conflict. Most broadly, the purpose of documenting conflict is to inform the public, many would also say that this is the main reason why we photograph suffering. However, even this causes some doubts. After all, a photograph in itself offers only a glimpse of the conflict and

does not tell us anything about the political situation. It is also very vulnerable to several means of manipulation. It is hard to say whether there is a single objective in photographing war or maybe it is a mixture of all of these.

All the critical analyses I have mentioned here ask relevant and important questions. In our daily lives, we become used to the visual language accompanying news articles and stories of conflict. We rarely think about the effects it can have on us and our perception of the issues we learn about. Often we may not look twice and simply skim through the image not paying attention to it, but if we look closely it appeals to our empathy. It reassures our safety while making us feel sorry about those who suffer. Critical analysts claim that looking at the war in such a way is passive, simplifying, objectifying, and, at the very least, not significant. Those are all valid observations about the role of the spectator in documenting conflict. Yet, it does not mean we should not continue to do so. Sheer awareness may not have a direct effect on improving the situation in the distraught regions, but it seems to be an intrinsic value. All things considered; it is better to look than to ignore. Perhaps behind all those questions about photography that I posed, there is a much simpler and much broader question — what is all this awareness really for, and what does it mean?

Photos

“The Struggling Girl” © Kevin Carter/Sygma/Corbis

“Suspected Lumumbist freedom fighters being tormented before execution, Stanleyville, Congo, 1964.”

“Turkish woman mourning her husband killed by Greek forces, Gazabaran, Cyprus, 1964.” © Don McCullin Contact Press Images