By Larissa Peltola, Editor, RightsViews.

The Armenian Genocide, which took place 106 years ago, today, claimed the lives of an estimated 1.5 million Armenians. While people around the world are now more aware of what occurred in 1915, following a global push for recognition of the genocide, few are aware of the lasting implications of the genocide which have carried on to this day. HRSMA alumna Anoush Baghdassarian (‘19) and Pomona College graduate Ani Schug (‘17) have undertaken the important and necessary work of collecting the oral histories of Syrian-Armenian refugees – the descendants of genocide survivors – to keep the memories of those who have perished alive.

What was the Armenian Genocide?

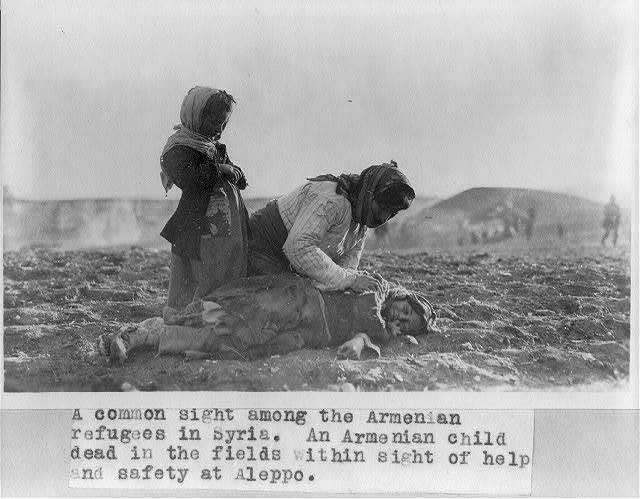

Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish lawyer who coined the term genocide, was moved to do so after hearing about the systematic annihilation of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915. Before WWI, Armenians – in what is now Turkey – totaled over two million. But by 1922, there were fewer than 400,000 left. The Turkish campaign of ethnic cleansing was swift and extremely brutal. Historian David Fromkin described the nature of the conflict: “Rape and beatings were commonplace. Those who were not killed at once were driven through mountains and deserts without food, drink or shelter. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians eventually succumbed or were killed.”

Armenians had lived in the southern Caucasus of the Ottoman Empire since the 7th century BCE, making it the first state to declare Christianity as the state religion in the 4th century, setting it against the powerful rise of Islamic states in the region. The roots of conflict may be traced back to religious identity. At the turn of the 20th century, the power and influence of the Ottoman Empire in the world was waning and calls to solidify a Muslim Turkish dominance in the Anatolia region came in the form of eliminating the Armenian community there. The near-collapse of the Ottoman Empire created dangerous instability among nationalist ethnic groups in the region. Labeled as an internal threat, Armenians were blamed for the failures of the Ottoman Empire and considered traitors and enemies.

In the spring of 1915, mass deportations began, followed by imprisonment, and the indiscriminate slaughter of Armenian men, women, and children. In the wake of the murders and displacement of the Armenian population, Turks took ownership of their properties and everything left behind. The Turks demolished any remnants of Armenian cultural heritage. To this day, Turkish officials denounce any mention of genocide against the Armenian population and much of the world still refuses to acknowledge the genocide. President Biden, on April 24, 2021, became the first American President to recognize the genocide, an important decision that sends a clear message to the world.

Armenians in Syria

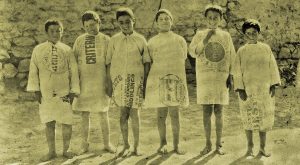

Of those that survived the massacres and death marches out of Turkey and surrounding regions, many Armenian refugees made their way to what is now Syria. By 1924, Armenian refugees in Aleppo numbered up to 100,000. From there, many moved into neighboring countries including Lebanon, France, Ukraine, Georgia, Russia, and onto the United States.

The civil war in Syria has been raging for a decade and has left over 5 million dead, with 5.6 million refugees, and over 6.2 million internally displaced. The conflict has put Armenians in a, particularly vulnerable state, again. As ethnic and religious minorities in Syria, Syrian-Armenians, descendants of the survivors of the genocide, have been targetted by multiple factions in the conflict, including the Islamic State and Al-Nusra. Armenian homes, cultural sites, hospitals, and schools, have been destroyed by extremist groups who view Syrian-Armenians as loyal to the Assad regime. Turkish involvement in the civil war has also left ethnic Armenians in peril; Turkish forces have occupied much of the Northern regions and have been accused of ethnic cleansing campaigns against Armenians, Yazidi, Kurds, and other religious minorities.

A century later, human rights abuses against Armenians continue.

Rerouted, Rerooted

Baghdassarian and Schug met in college, their passion for human rights and Armenian causes prompted them to establish the Armenian Student Association to celebrate Armenian culture. Upon graduation, Baghdassarian, from Claremont McKenna College, and Schug, a graduate of Pomona College, were awarded the Davis Projects for Peace, a fellowship program that commits $1 million annually to fund projects that advance human rights, social justice, and sustainability. Their project took them to Armenia in the summer of 2017 to collect testimonies and oral histories of Syrian-Armenian refugees. Their goal was to empower their participants and share the stories that have not been given the attention they deserve.

While their fellowship lasted only a few months, Baghdassarian and Schug had a much larger vision for their project.

After returning to the United States, they founded the Rerooted Archive, a documentation project that “preserves these personal, on-the-ground perspectives of 100 years of Syrian-Armenian history from its roots of survival, to its vibrancy in Syria, to the precipice of dispersion.” Building from the 80 interviews they collected in Armenia during their fellowship in 2017, their archive currently has over 200 testimonies and oral histories of Syrian-Armenians that resettled in Armenia as well as around the world including France, Australia, Argentina, and others. These testimonies cover a wide range of topics with the goal of sharing a rich collective history, tradition, religion, and culture with the world, and empowering and advocating for the community’s needs in Syria, Armenia, and beyond.

“The point of this project is to make their voices heard,” Schug stated. “Older [narrators] would tell us, ‘our parents and grandparents never got their stories told.’” Baghdassarian and Schug took care to let their subjects guide each interview. They recounted their families’ experience with the genocide, how they ended up in Syria, their everyday lives, what it was like to be Armenian away from their ancestral homes, as well as their

wants and dreams. “We aim to be careful not to retraumatize our narrators,” explained Schug, “but the point…. of [these testimonies] was to get community stories…that is the texture that is often missing in stories of minority communities.”

The name of their archive is one that is deeply personal to the Armenian people. According to Baghdassarian, “the title of the archive is Rerooted, and that’s a play on words for ‘rerouted’ because Armenian people have been rerouted so many times but every time we reroot ourselves and build thriving, strong communities.” Documenting these oral histories, creating a space for education and discourse, and using archives as a tool to secure future histories and testimonies, further grounds these complex and powerful narratives into a shared collective history.

To this end, the goals of Rerooted are: preservation, education, and justice. The archive publishes testimonies, in video, audio, and written form, personal and historical photos, documents, and more, in order to preserve the customs, culture, and histories of Syrian-Armenians. To accompany their interviews, participants were encouraged to provide the archive with a commemorative token of their lives, be it personal photos, the music they composed, and more. Many of the interviews conducted were in the endangered Western Armenian language, which was the language of the Armenians killed in the genocide a century ago.

To this end, the goals of Rerooted are: preservation, education, and justice. The archive publishes testimonies, in video, audio, and written form, personal and historical photos, documents, and more, in order to preserve the customs, culture, and histories of Syrian-Armenians. To accompany their interviews, participants were encouraged to provide the archive with a commemorative token of their lives, be it personal photos, the music they composed, and more. Many of the interviews conducted were in the endangered Western Armenian language, which was the language of the Armenians killed in the genocide a century ago.

Rerooted has also expanded its efforts to become a one-stop educational resource for high schools and colleges/universities. The team has created a series of lesson plans and multimedia resources. According to Baghdassarian, “We hope others can use this as an educational resource… there are so many intersections that are relevant here to different disciplines…what it’s like to be an ethnic and religious minority in the Middle East, what it’s like to be a refugee, what it’s like to be displaced so many times.” When asked how oral histories, in particular, would serve as an educational tool, she explained, “[they] are not to create sympathy or pity. But you can connect to somebody by hearing their story, seeing that they are a person and not just a number or a statistic. One can learn about the conflict through stories.” Perhaps most importantly, “oral histories humanize. And that is the goal.”

Lastly, this project is grounded in promoting justice and accountability. While justice via reparations, or even recognition, still seems a distant dream, Armenian refugees still have their voices. “As far as we knew,” Schug explained, “the Armenian community was not being asked about what justice meant to them.” Through these oral histories, a form of justice can also be achieved by revealing once suppressed narratives, creating historical dialogues, and by reshaping the dominant narratives being told. The archive gives voice to those that have been silenced and persecuted for over a century. It will also help inform people about Syrian history, about the lives and plight of ethnic minorities in the country as well as highlight how to help refugees who have settled in other countries.

Despite being launched just a short time ago, the archive is already making a tremendous impact in the human rights arena and in international law. Rerooted signed a memorandum of understanding with the United Nations’ International Impartial and Independent Mechanism for Syria (IIIM) in 2019, which documents human rights violations committed in Syria, contributing its interviews to UN documentation efforts. The archive also provides various oral histories and evidence it has collected to the Syrian Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC) as well as European courts that are seeking to prosecute the Assad regime. This summer, with legal fellows and undergraduate interns, the archive plans to expand, providing more legal analysis to those working on accountability for Syria, and to prepare for an official launch in the fall, where they will share the archive and its resources with the world.

More information about Rerooted can be found here: Ihttps://www.rerooted.org/

_________________________

The Rerooted Archive is grateful to have been funded to this point through grants and individual donors. As they prepare to formally launch the archive and move to a new phase of growth in the project, Rerooted is seeking new sources of funding and partnerships. They can be contacted at [email protected]

Ani Schug is a co-founder of the Rerooted Archive. She currently works as a DOJ Accredited Representative in Philadelphia, PA, assisting immigrants regularize their status and reunite with family members. Ani graduated from Pomona College in 2017 where she studied Politics and Middle Eastern Studies. She loves learning languages and studying issues of Diaspora and minority identities in the Middle East.

Ani Schug is a co-founder of the Rerooted Archive. She currently works as a DOJ Accredited Representative in Philadelphia, PA, assisting immigrants regularize their status and reunite with family members. Ani graduated from Pomona College in 2017 where she studied Politics and Middle Eastern Studies. She loves learning languages and studying issues of Diaspora and minority identities in the Middle East.

Anoush Baghdassarian is a co-founder of the Rerooted Archive, and is a JD Candidate at Harvard Law School. She has a Master’s in Human Rights Studies from Columbia University, and a Bachelor’s in Psychology and Genocide Studies from Claremont McKenna College. Anoush has a career focus on transitional justice and international criminal law and some of her work experiences include interning as an advisor to the Armenian Permanent Mission to the UN, and serving as an upcoming visiting professional at the International Criminal Court.

Anoush Baghdassarian is a co-founder of the Rerooted Archive, and is a JD Candidate at Harvard Law School. She has a Master’s in Human Rights Studies from Columbia University, and a Bachelor’s in Psychology and Genocide Studies from Claremont McKenna College. Anoush has a career focus on transitional justice and international criminal law and some of her work experiences include interning as an advisor to the Armenian Permanent Mission to the UN, and serving as an upcoming visiting professional at the International Criminal Court.

Photos

“68th anniversary of Armenian Genocide in Western Armenia and Turkey” by 517design is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Syria – Aleppo – Armenian woman kneeling beside dead child in field “within sight of help and safety at Aleppo” CC Near East Relief

“Refugee Armenian and Syrian boys dressed in American flour sacks ca1920 LOC3c30739u” is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

All other photos courtesy of Ani Schug and Anoush Baghdassarian