By: Kyoko Thompson, Staff Writer at RightsViews

Odds are that, if you follow the news, you’re aware of what’s happening in Hong Kong. The protests—which began in June as the result of a proposed extradition bill—have taken over the media of late, with citizens taking to the streets in unprecedented numbers. During one such a protest on June 17th, for example, an estimated 1.7 million people marched from Victoria Park to Hong Kong’s Legislative Council complex to demonstrate their desire to keep Hong Kong free and independent. With crowds like those, the Chinese government has certainly been paying attention, yet after over a hundred days of protests, participants have yet to see definitive results in regards to their demands. Even worse, the sustained protests have led to deaths, injuries, and thousands of arrests, as well as incidents of police brutality.

Civil resistance, as defined by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, is a powerful tool for people to fight for their rights without using violence. The Center writes, “When people wage civil resistance, they use tactics such as strikes, boycotts, mass protests, and many other nonviolent actions to withdraw their cooperation from an oppressive system.” At the moment, levels of civil resistance have been climbing, signifying a global strategic trend. According to Dr. Erica Chenoweth of Harvard University, episodes of violent insurrections have been declining around the world since the 1960s, while unarmed demonstrations have risen almost exponentially. In fact, from 2010 to 2018, there were nearly double the number of nonviolent campaigns than there were from 1990 to 1999.

At first glance, these statistics appear positive. After all, if more people are speaking up and opposing policies and regimes that they deem to be unjust or ruthless, but they aren’t doing it violently, wouldn’t that mean the world is becoming a better place? Not according to Dr. Chenoweth’s data. In fact, civil resistance is much less effective today than it was in the 20th century—and that, she explains, is its paradox.

On October 9th, Dr. Chenoweth visited Columbia’s School of International Affairs to talk about what she calls “The Paradox of Civil Resistance in the 21st Century” at The Eleventh Annual Kenneth N. Waltz Lecture in International Relations. Award-winning researcher, published author, and one of Foreign Policy magazine’s Top 100 Global Thinkers of 2013, Dr. Chenoweth is a proven expert in the field of international relations and peace research. Using data collected from global incidents of resistance—237 violent and 270 nonviolent—from 1945 to 2006, she was able to distinguish the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful campaigns and draw conclusions as to why so many of them fail to achieve change; conclusions that, while fascinating, stand to discourage even the most civically minded individual.

Why Nonviolent Resistance Has Succeeded in the Past

The United States we know today is what it is largely because of the civil resistance movements of the 1900s. The women’s suffrage movement, for example, gave women the right to vote nearly one hundred years ago. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s led to the desegregation of public facilities and schools across the country, the repeal of racially prejudicial laws, and the establishment of new ones to protect the civil liberties of all Americans. The Anti-War Movement, as well, pressured federal representatives to pull U.S. military forces out of Vietnam and abolish the draft in 1973. Indeed, civil resistance in the 20th century was a highly effective method to influence political reform in the United States. To better understand why civil resistance is no longer effectual in the 21st century, despite being more popular than ever, it is helpful to consider what made those earlier movements so successful in their time.

In her lecture, Dr. Chenoweth explained that first of all, the probability of a campaign succeeding increases in proportion with its number of participants per capita. And, because people are less willing to risk harm via violence, nonviolent campaigns tend to be much larger than the average armed campaign—about eleven times larger, in fact. Large numbers mean a larger disruption, and the main function of civil resistance is to use so many people that an opponent—a corporation, organization, or government—can no longer rely on their support to function. This creates what Dr. Chenoweth calls a “crisis moment,” where people who are not directly involved in resistance are forced to rethink their interests (for instance, if a small business owner suddenly finds himself boycotted for refusing to employ people of color, he may feel obligated to change his policy not because he was emotionally swayed by the cause, but to avoid further financial loss).

Given their size, it makes sense that so many of the political movements of the 20th century were successful at affecting behavior change. Consider the Iranian Revolution, which took place from 1978 to 1979. According to Charles Kurzman’s 2004 publication The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, more than 10% of Iran’s total population participated in the December 1978 demonstrations that immediately precipitated the fall of the Iranian monarchy. The French Revolution, in contrast—a staple among historical revolutions and a symbol for the pursuit of freedom throughout the Western world—is estimated to have included only 1-2%.

It isn’t just how many people are represented in a movement that makes it effective, however; it’s also who is represented. Movements in which women are equally represented, for example, are much more successful. “When there is gender parity…there is a much higher rate, or predictive probability, of success for that campaign,” explained Dr. Chenoweth. Unarmed participants are beneficial to a movement, as well; as when participants are unarmed, it is politically risky for a state to engage in acts of suppression. Recall the massacre at Kent State University, arguably the most pivotal moment of the entire anti-war movement of the 60s and 70s, where four unarmed college students were shot and killed by the Ohio National Guard. Acts like these—including police aggression—are seen as inhumane and unnecessary against unarmed civilians, and only serve to legitimize a movement, not quell one (conversely, they may be seen as justified against armed insurgents). This is part of the reason why nonviolent campaigns are particularly successful against repressive regimes; 26% more effective than their violent counterparts, according to Dr. Chenoweth’s data.

What has changed in the past decade?

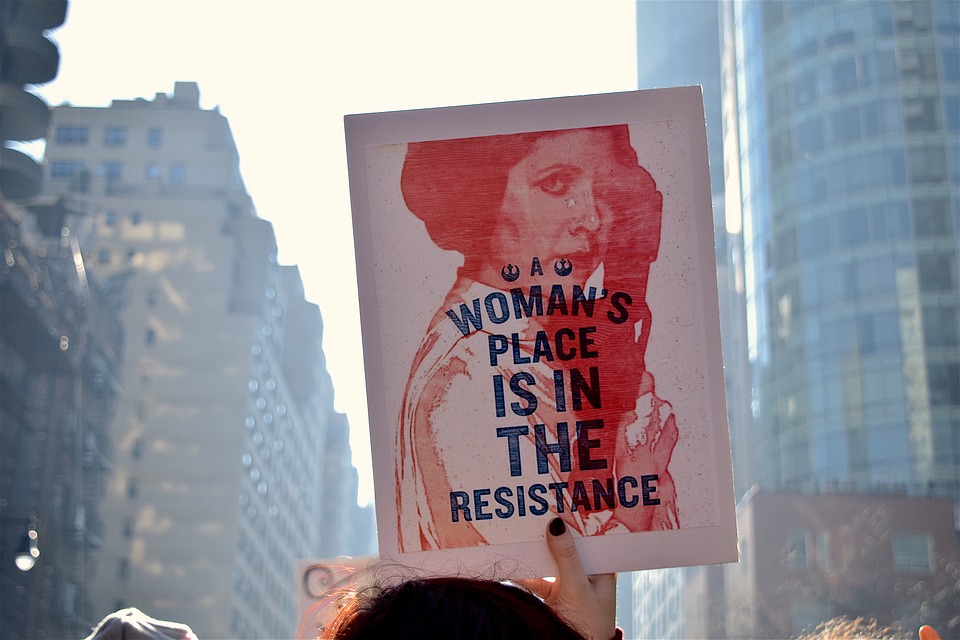

One aspect of the decreased effectiveness of civil resistance today compared to the 20th century is size. While the number of movements have certainly increased, the movements themselves are much smaller today than they used to be. There are some exceptions to this rule, such as the 2017 Women’s March—the largest demonstration in U.S. history—and the #enough school walkouts for better gun control in 2018. In general, however, demonstrations have shrunk in size.

This may be counterintuitive, considering the perfusion of digitally driven activism encountered in social media and online. However, while a social media campaign may facilitate rapid mobilization, it does not sustain it. A video of police officers beating up a protester on Twitter may trigger throngs of people to take to the streets, but it lacks the daily church basement meetings and rigorous community preparation common to the movements of the 20th century. It also does not remove any pillars of support from the opponent, said Dr. Chenoweth, which would lend political influence to the movement.

Dr. Chenoweth further argued that civil resistance is less resilient to repression than it once was because regimes have simply gotten better at repressing. Consider all the technological advancements of the last twenty years—the same innovations that brought us the iPhone 11 and Beats by Dre have also yielded tools that governments can use to surveil and promote their own agendas. Even more ominous is that tech companies and government agencies might actually be sharing best practices for suppressing nonviolent demonstrations with each other. In many ways, technological gains to states’ suppression tactics far outweigh any leverage movements may have garnered from the existence of social media platforms and police tracking apps. After all, what good is a hashtag when you’re fighting facial recognition software?

Resolving the paradox: does nonviolent resistance have a future?

The picture Dr. Chenoweth’s research paints may look a little bleak. It may even have you reconsidering attending the next political demonstration in your city. Given all of the above, it’s natural to question if and how civil resistance will ever regain its standing in the fight for rights, freedoms, and justice around the world. Is there any hope? Dr. Chenoweth thinks so; but only if you buy into the argument that there are things movements are doing differently today, or that something has fundamentally changed within our system. If you do, then you should take that into consideration when launching a campaign.

Know that just because a movement is nonviolent does not mean it will be successful, but on the flip side, violent ones are even less so. Size may not guarantee success, either—the Women’s March didn’t significantly alter U.S. policy, and student walkouts didn’t tighten the government’s reins on gun control—but many votes are still better than one. Utilize social media, but don’t let it take the place of a good old-fashioned strategy—a hashtag may not disable facial recognition software, but a mask will certainly render it useless. And just as opponents share information on their methodology, so too must campaigns diffuse their knowledge; because building on the experience of others is a surefire way to improve your chances of success.

When all else fails, though, don’t be discouraged. After all, the rights you enjoy today were borne on the backs of those that came before you. Civil resistance is not yet obsolete, and your opinion matters—no matter what the opposition says. So, pick up that sign, put on that pink hat, and get out there.

About the speaker: Dr. Erica Chenoweth teaches courses such as “Civil Resistance: How it Works” and “The Politics of Terrorism: Causes and Consequences from a Global Perspective” at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. She co-founded the award-winning blog Political Violence @ a Glance and hosts Rational Insurgent. Her next book, Civil Resistance: What Everyone Needs to Know, comes out in 2020. To hear Dr. Chenoweth speak on this topic, check out her 2013 TEDx talk in Boulder, Colorado.