By: Parima Kadikar, guest contributor. Parima is a rising senior at Columbia College studying Middle Eastern Studies and Human Rights.

In an exceedingly digital world, humanitarian aid for refugees is being revolutionized by technological innovation. International non-profit organizations and UN agencies have begun to employ strategies like biometric scanning and blockchain technology to streamline aid delivery and prevent identity fraud. While these strides are noteworthy examples of progress, it is also important to address the potential privacy concerns that could result.

In the context of conversations sparked by the Patriot Act— Congress’s response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks which expanded federal jurisdiction over private data and communications for the purpose of intelligence gathering– and, more recently, by the Cambridge Analytica data-mining campaign which harvested the data of millions of Facebook users without their knowledge or consent for conservative political campaigning, many Americans are protective of both their physical and digital privacy. The evidence of this can be seen from taped webcams in college classrooms to frustration with the TSA at airports to the rising popularity of secure messaging apps for activists.

For refugees, however, concerns about privacy permeate all aspects of life. If they are living in a country with strong xenophobic sentiments, refugees may wish to conceal their identities due to fear of discrimination. Additionally, many escape or resettlement routes taken by refugees as they flee their home nations require unauthorized border crossings. BBC has produced a video simulating the privacy dangers associated with this when an asylum seeker has a cell phone; if their location is being tracked as they flee to safety, they could be targeted by border authorities and their asylum requests could be denied for entering unauthorized.

As well as the concern about losing asylum status in their destination, refugees face the possibility that the group(s) persecuting them– whether it be a government regime, militia, or other non-state actors– could also discover their location or involvement in activism through technology usage. Such a discovery could present immediate threats to a refugee’s life, or at the very least prevent them from ever returning to their home country.

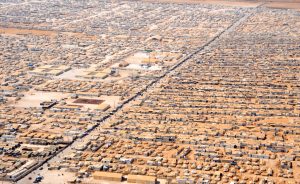

One attempt to secure refugee data is the World Food Programme’s (WFP) use of biometric scanning and blockchain technology to distribute aid in Jordan’s Zaatari camp, the second largest refugee camp in

the world. “Eye Pay,” a project within the organization’s “Building Blocks” program, allows refugees to access a digital wallet by scanning their irises at participating shops within the camp.

While this technology is impressive, it raises concerns about feasibility. Building Blocks runs on a private-permission blockchain, which addresses data security concerns but is difficult to expand in scale.The WFP’s technology is supported by the cryptocurrency Ethereum, meaning that users who buy, sell, and mine this currency validate the chain. Therefore, the market for Ethereum must grow significantly before a program like Building Blocks can be increased in scope.

In order to successfully manage the data for large refugee populations, WFP is faced with a question of how to incentivize Ethereum holders to increase the level of coordination in these initiatives. As

blockchain technology provides a significantly more secure alternative to storing refugees’ data on UN databases, a successful means of incentivizing coordination so as to expand the existing program could lead to outcomes that redefine refugee aid.

However, until such technology can be implemented on a larger scale, the threat of privacy breaches remains very real for refugees. In order for a displaced person to receive official refugee status from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (and, as a result, access to aid earmarked for refugees), they must submit a great deal of personal data to the agency. While it is understandable that UNHCR needs to collect information like employment and health records from applicants to prevent identity fraud, Privacy International, a non-profit organization that pressures companies and governments to implement better data privacy regulations, warns that issues arise when it shares jurisdiction over this data with other groups.

It is difficult to know about specific instances of UNHCR privacy breaches as the agency does not publicize this information. A 2014 breach of Australia’s Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP), however, led to the publication of the personal details of over 9,000 unsuccessful asylum seekers on the DIPB website. These details included full names, gender, citizenship, date of birth, period of immigration detention, location, boat arrival details, and the reasons that each applicant was denied refugee status.

A lawsuit was subsequently filed against the DIBP, alleging that the asylum seekers whose information was publicly revealed were treated unfairly during the review process. While the High Court of Australia ruled that the representative litigants in this case were treated fairly by the government, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is currently (almost 5 years later) assessing whether or not the affected asylum seekers should be compensated for the violation.

Though the Australian breach occurred within a national government and not the UNHCR, it offers a high-profile example of how displaced people can suffer when their privacy is violated. As the global refugee crisis continues to intensify with each passing year, it is imperative that the UNHCR and its partners dedicate more resources and manpower to addressing privacy concerns. The few examples discussed in this blog, such as the WFP’s Building Blocks program, are steps in the right direction. However, until they can be implemented on larger scales, refugees remain especially vulnerable.