On November 12, Pepe Julian Onziema spoke to attendees of an event focusing on “LGBTQ+ Rights in a Global Perspective,” moderated by Professor Katherine Franke of Columbia Law School and the Center for Gender and Sexuality Law. Onziema, who is from Uganda, is currently a Fellow at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia. He is an outspoken activist for LGBTQ Rights in Uganda and is the Programs Director of the non-profit organization “Sexual Minorites Uganda” (SMUG). His talk was centered around the history of LGBTQ persecution, as well as activism, in Uganda and the role that SMUG has played in making changes for acceptance and policy change.

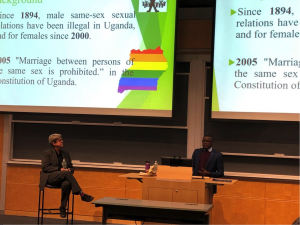

Giving some initial background on Ugandan LGBTQ history, Onziema explained that Uganda was colonized by the British and since 1894 male same-sex relations have been illegal—for females, it was made illegal more recently, in 2000. Further entrenching the criminalization of LGBTQ identity, the Uganda Constitution was amended in 2005 to declare that “Marriage between persons of the same sex is prohibited” and is “against the order of nature.” Today, Uganda is still highly LGBTQ-phobic. It is important to note, said Onziema, that the homophobia in Uganda stems vastly from colonizing countries, not from pre-colonial conceptions of gender which did not present as homophobic.

SMUG was created in 2004 to challenge the discrimination and maltreatment of LGBTQ folks in Uganda. Onziema described that their entry point into the advocacy space was through HIV/AIDS discourses—SMUG hosted an international HIV/AIDS meeting about the stigma against same-sex relationships and HIV/AIDS. Since then, SMUG has expanded its agenda and developed a system based on four pillars: advocacy and law reform, research, capacity strengthening, and safety and protection. SMUG is “for the community, by the community,” explained Onziema. Everything they do is to “support Ugandans with crisis response and human rights-based programs.”

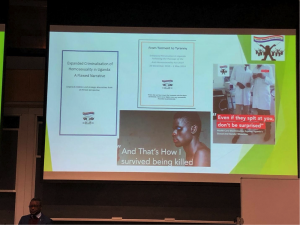

One form of advocacy that SMUG does, said Onziema, is litigation. Although the Ugandan Constitution clearly prohibits same-sex marriage, “in Uganda, as homophobic as it is, always in laws you can find gaps,” said Onziema. SMUG has participated in several victories for the improvement of rights for LGBTQ folks, including winning a court case in which two suspected lesbians had had their houses searched illegally by arguing that their rights to privacy and dignity had been violated. In a case in which Onziema himself was a plaintiff, a local tabloid had released a newspaper “outing” many suspected LGBTQ folks, including providing personal addresses and phone numbers to the public, under the headline “Hang Them, They are After Our Children.” SMUG filed a violation of the right to privacy and dignity of person and won that case as well. Yet, Onziema described that SMUG still has a ways to go to get legal recognition of LGBTQ persons— remarkably, even the organization itself has been denied registration because its name is “undesirable” to the Ugandan government.

That being said, Onziema and SMUG hold a unique connection to the United States and Columbia themselves—Professor Franke, who is also on the Board of Directors at the Center of Constitutional Rights, was counsel to SMUG in a Massachusetts federal court case Sexual Minorities Uganda v Scott Lively. Lively, a homophobic evangelical, had been travelling for years to Uganda preaching anti-LGBTQ hate rhetoric. Onziema described that Uganda is 86% Christian and highly religious, making it a “soft spot” for religious evangelicals like Lively to sow homophobic seeds. SMUG filed in court under the Alien Torts Statute, which allows foreign victims of human rights abuses to seek civil remedies in court. Onziema said that SMUG won the case in 2017, and Lively lost on appeal again in 2018. Onziema has truly seen an impact now in Uganda—he said that US evangelicals have now stopped speaking publicly homophobic messages when they visit. “Fighting this was a really a plus for us,” he said. As well as its impact on SMUG and Uganda, Franke also explained how monumental the Lively decision was: for the first time, a US court held that sexual orientation-based persecution is actionable under the Alien Torts Statute. This is a landmark precedent.

SMUG and Uganda still face many challenges today with homophobia not only within state law but also in state and police action. At Ugandan Pride 2016, said Onziema, 16 people, himself included, were rounded up and arrested while the police surrounded the event carrying AK47s and batons. He was beaten to the point where he lost hearing in his left ear. LGBTQ people are “just trying to be their authentic selves,” he said, “and in doing that they fall into the hands of the law that criminalizes that.” On more nuanced levels, LGBTQ folks face family rejection, eviction, expulsion from schools, lack of employment, and a lack of access to the justice system. SMUG works with the community with its “Know Your Rights” Project that teaches people about the Ugandan Bill of Rights and encourages people to get reparations where they are due. “Knowing our rights and knowing that we can actually go to court is important,” said Onziema. “We are trying to challenge the very laws that criminalize our existence.”

Other projects that SMUG works on are training to health service providers for the queer community, running counselling at their own SMUG clinic, creating a hotline for psycho-social support with their “see the invisible” campaign, and keeping in contact with people in the community constantly. Onziema described that because SMIG began as an HIV/AIDS advocacy organization, much of the financial support benefits men who have sex with men, gay men, and trans women, but can leave out other queer identities such as lesbians, trans men, and women who have sex with women. In HIV studies, he said, there is very little data on transmission other than men with men—this leads to some tension in that “as a trans man, I struggle to keep receiving money that is only catering to a smaller group.” Yet, this will not be the agenda forever said Onziema. SMUG hopes to only grow in its efforts.

Onziema gave his audience several ways to support SMUG: solidarity, working in the organization, urging our leaders to keep LGBTQ rights on the agenda, and getting media coverage of our stories. Onziema and SMUG are fighting tirelessly for rights for all sexual orientations in Uganda, truly giving us LGBTQ rights in a global perspective. To broaden your perspective even more, visit sexualminoritiesuganda.com to learn, seetheinvisible.ug to campaign, and smuginternational.org to donate.

By Rowena Kosher