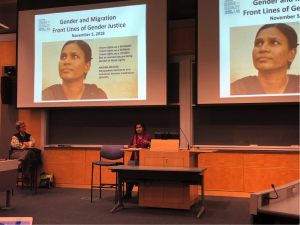

What is the connection between gender and migration? Between the garment industries in Bangladesh and the United States? And what advocacy strategies can we learn from these connections? These were some of the questions addressed by Chaumtoli Huq on Monday, November 5 in her talk on “Gender and Migration: The Front Lines of Gender Justice,” facilitated by Professor Katherine Franke of the Law School and the Center for Gender and Sexuality Law at Columbia. This discussion was part of a series of talks in Professor Franke’s Law class “Gender Justice” this semester.

Chaumtoli Huq is an Associate Professor of Law at the CUNY Law School and the founder of non-profit organization Law at the Margins. Huq is a self-proclaimed “social justice lawyer,” interested in working not only top-down from elite institutions and courts to gain victories for clients and communities, but more importantly in working in and through the communities, she assists, taking the lead from those who would be most impacted by a decision. Much of her work focuses on South Asia (especially Bangladesh) and the United States, including how the two countries are intrinsically connected.

Beginning her talk on gender and migration, Huq stressed the need for a non-linear view of migration. Typically, she said, we think of migration as the movement of a person from one state to another, but we fail to recognize the other versions and nuances important to the concept of migration such as urban/rural, seasonal, within and across communities. If we only think of migration linearly, she stated, we miss the informal networks in which migration occurs, and importantly we don’t see the role that the state plays as a conduit for capitalism. Describing her work as s transnational, Huq writes: “We have to look past the local and the global and the here and the there. We have to look at the lives of the people we are looking at.” Huq, adds, however, that we must also see the ways in which migration and immigration themselves are gendered.

Huq demonstrated these connections by discussing the development of the garment industry in 2000 that happened almost simultaneously in Bangladesh and in the United States. In Bangladesh, said Huq, 80% of the workforce in the garment industry is women. When the industry began, she said, there was a belief that the only way to compete in the global market was through cheap labor—synonymous, she said, with gendered labor. Women were actively recruited into the garment industry, demonstrating the role of the state and economy in structuring a gendered workforce “outwards and into the garment industry.” Huq explained that approximately $25 Billion is riding on the gendered labor in the garment industry…and that the goal is to double this, primarily by extracting cheap labor from a predominantly female workforce. In Bangladesh, says Huq, to enter the industrial workforce, women have also been removed from rural areas to urban (internal migration); another $14 Million revenue comes from migrant domestic workers.

At the same time these changes in gendered labor were occurring in Bangladesh in the 2000s, NYC was developing an equally large garment industry. Changes in immigration policies at the time produced an incentive for many Bangladeshi low wage workers to immigrate to the United States and enter into low wage jobs. Transnational migration evolved into internal migration in the States, as well. Huq pointed out that there are several thriving Bangladeshi communities in Buffalo (where construction jobs were available), the Hudson Valley (cheap factory labor), and Detroit which all originated from workers moving from NYC outwards.

What these patterns show, said Huq, is that economic pushes and pulls are important to understand in order to see immigration’s gendered consequences. Domestic work was and still is immensely popular among migrants from South Asia. But it is also historically low paid, low benefit, gendered labor. Following 9/11 and the US War on Terror, Muslim women faced new challenges. Often, she said, women were left behind while Muslim men tended to be deported, forcing them into a position of needing to enter the workforce for the first time. Many women entered domestic low wage jobs in the informal economy.

Huq currently works with many Bangladeshi and South Asian women who are part of this economy towards developing empowering female movements, including unions, sewing co-ops, and other labor organizing in the Bangladeshi NYC diaspora. One organization she worked with, Andolan, has helped advocate for rights for migrant and domestic women workers. Importantly, Huq stressed that these movements can draw from the interconnectedness of migration and gender. “If they are interconnected processes,” she said, “then it really doesn’t matter whether you’re here or there; your advocacy can take place where you’re at.” Further, there are multiple points in which our advocacy and activism can focus on communities we are trying to serve.

This is also what Huq does in her organization, Law at the Margins, which is an online law and social media advocacy group focused on exploring narratives of social justice in blogs, webinars, and online content. Writers from impacted communities share their perspectives, creating a valuable hub for content for social change activists to access. This perspective of focusing on the voices of the impacted helps to align Huq’s law practice with her values. When asked about how she reconciles the fact that often lawyering is elites speaking to elites for elite victories in court, Huq responded that she prioritizes working with community-based organizations. “My job is to not have a job,” she replied. “Strong people don’t need leaders…it’s important to be guided by folks.” Top-down lawyering can be valuable, of course, but it has to be working in tandem with community-based groups, she explained

Many of Huq’s suggestions for advocacy involve asking questions such as what voices are here? And who needs to be in the room? As she points out in relation to advocacy for Bangladeshi garment workers, “I’m not a garment worker.” This is why our activism has to be local.

Huq closed her talk by proclaiming that transnational advocacy also means avoiding US-centricity, listening more to those affected, keeping away from neocolonial relationships, and changing the way we arrive at our policies. The garment industry is only one way in which gender and migration are connected, as with our advocacy. A quote that Huq shared in her presentation by South Asian Activist Kazi Fouzia aptly demonstrates this: “We always remember that we are part of a global chain. If we do not support one another, we will not be able to bring about social change.”

By Rowena Kosher