By Ashley E. Chappo, editor of RightsViews and a graduate of Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs and Columbia Journalism School

Human rights, specifically the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), are the focus of this year’s International Day of Peace, or “Peace Day,” which takes place across the world each year on September 21.

This UN-designated day of observance advocates peace action and education in spite of ongoing human conflict through peace-building activities, a global minute of silence, intercultural and interfaith dialogues, vigils, concerts, feasts, and marches. This year’s theme is “The Right to Peace – The Universal Declaration of Human Rights at 70.”

The timing for the theme is apropos: it comes at a period when the human condition is increasingly vulnerable, beset by global conflict and dependent on world leaders who have turned their backs on international cooperation. During this state of prolonged human suffering, the power and failings of a single document of 30 human rights ideals comes into pronounced focus. Why should we celebrate the UDHR? Now 70 years old, has it made any real difference to peace and the protection of people?

One lens through which to view these questions: the current state of international affairs, in which we grapple with intractable problems like the Syrian Civil War, ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, crisis in Congo, civil war in Yemen, war in Afghanistan, conflict in Iraq, violence in Venezuela, and a crisis of 68.5 million people forcibly displaced worldwide. Perhaps it’s time we relied less on hope and principles, and a little more on action.

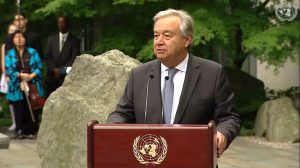

UN Secretary-General António Guterres seemed to openly acknowledge doubts about the ability of international compacts to uphold human rights in the present day as he spoke today at UN Headquarters in New York City. At the same time, he also pushed back against these uncertainties with vigorous optimism.

“When we are celebrating the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we know that human rights are violated in so many parts of the world, we even know that the human rights agenda is losing ground,” Guterres said. “But we don’t give up because respect for human rights and human dignity is a basic condition for peace.”

Forging ahead against challenges was the key sentiment of today’s remarks.

“We are here because we are determined and we do not give up. We see conflicts multiplying everywhere in the world. We see links between conflicts and terrorism. We see insecurity prevailing. We see people suffering. But we don’t give up,” he continued.

Children dressed in white played the violin in the Peace Garden at United Nations Headquarters. Guterres concluded the ceremony by ringing the Peace Bell to commemorate Peace Day.

Overall, the feeling from the ceremony was uplifting. But are words and gatherings anything more than a good sound bite or a symbolic gesture? Why do we need the UDHR in 2018 when it has proven ineffective at preventing human atrocities in its 70-year history?

One good reason: it represents an important milestone in our human rights fight that sets a common standard for all peoples and all nations. Since the UDHR was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948, its words have reverberated across continents. Its 30 articles affirming individual rights have been translated into some 370 languages, making it one of the most translated documents in the world.

Furthermore, although not legally binding or a treaty itself, the UDHR is widely considered the foundational document of international human rights law that has served as inspiration for many of our world’s legally-binding international human rights treaties and resolutions. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1965) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), for example, both came into force as a direct outcome of the UDHR, enshrining in law many of its ideals. Similarly, the Convention Against Torture (1984) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) track their roots to the UDHR. Traces of its articles are also found in the language of many national constitutions.

As of 2018, all UN member States have ratified at least one of the nine international human rights instruments that make up the core body of legally-binding international human rights law, with the majority ratifying four or more of these treaties. Once a State becomes party to any one of these international treaties, it accepts certain obligations to respect and fulfill these rights.

In this regard, Guterres’ optimism has legs. His hopefulness was shared many years ago by Eleanor Roosevelt, chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights and a prominent author of the UDHR. She believed fully “in the force of documents which do express ideals.”

However, she also believed that human rights begin in small places, close to home.

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.” — Eleanor Roosevelt, United Nations, 1958

A key part of upholding the UDHR, she notes, is civic action to ensure these rights; action that demands response from leaders who have either turned a blind eye or who openly defy justice.

“Without concerted citizen action to uphold [rights] close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world,” she said in a speech at the United Nations.

Join RightsViews in honoring the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on Peace Day 2018! As part of the global celebration of this important document, which continues into December, you can add your voice in your own language to the Declaration as part of a UN collaborative video project. You can also read an illustrated version of the UDHR, available on the UN’s website.

Ashley E. Chappo is a recent graduate of Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs, where she studied human rights and international conflict resolution, and Columbia Journalism School, where she studied multimedia and investigative reporting. You can follow her on Twitter @AshleyChappo. She is editor of RightsViews.

I hope we all join together for a world of peace and love, thanks for article