By Jason Hung, a guest blogger from the University of Warwick

Currently, there are an estimated 118,995 refugees living in the U.K., composing less than one percent of the country’s total population. Three to ten percent of these refugees are thought to have a physical or mental disability. Due to the small number of disabled refugees living in the U.K., the rights of these refugees have often been disregarded, according to Keri Roberts and Jennifer Harris, research fellows from the University of York who generated data on the numbers and social characteristics of disabled refugees and asylum seekers living in Britain. Their research, which was completed in collaboration with the Refugee Council, found that U.K. communities are unable to provide sufficient aid for these vulnerable groups.

“Disabled people in refugee and asylum-seeking communities frequently experienced great hardship,” the authors note. “Considerable confusion about the responsibilities of different agencies and National Asylum Seekers Service (NASS), a lack of coordinated information and service provision, and gaps in professional knowledge on disability-related entitlements increased the difficulties experienced by disabled people in refugee and asylum-seeking communities.” For example, disabled refugees in the U.K. encounter inappropriate housing, as well as inadequate aid and equipment. There is also no official source of data about disabled refugees in the U.K, and it is noteworthy to highlight that even the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) fails to estimate the number of disabled refugees who have been resettled. Roberts and Harris conclude in their report that the insufficient statistical and empirical data about disabled refugees implicates the possibility of an invisible population of disabled refugees residing in the U.K. The extent of the social needs of these refugees remains unknown.

A lack of financial support and access can bar disabled refugees from learning English and other valuable languages, such as British Sign Language (BSL) for deaf individuals, for example. In addition, communication difficulties have discouraged some disabled refugees from seeking community support and accessing benefits. One Vietnamese refugee missed out on disability-related benefits for 22 years because he was not properly informed about the availability of the Disability Living Allowance, according to a report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. The same report noted that a disabled Somali woman was never properly informed about how to apply for humanitarian aid due to language barriers. Without a helping hand, disabled refugees could find it challenging to live in the U.K. unless their English proficiency improves.

The year 2017 has further marked a bleak future for disabled refugees in the U.K. The government terminated the acceptance of disabled child refugees arriving from the war in Syria and other countries, including Libya, Yemen and Iraq. The Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme hoped to resettle 3,000 of the most vulnerable disabled child refugees prior to its suspension. These children must now stay in refugee camps, instead of being placed in the U.K. Shantha Barriga, director of Human Rights Watch’s disability rights division, denounced this action, stating, “Shutting the door on vulnerable children is an affront to British values…. People with disabilities endure unimaginable hardship during conflicts, and many faced huge hurdles in escaping the violence.” Lisa Doyle, head of advocacy at the Refugee Council, supplemented this statement by adding that disabled refugees are by definition the most vulnerable groups. The U.K. government should thus prioritize the resettlement of these cohorts and accommodate them safely, advocates argue.

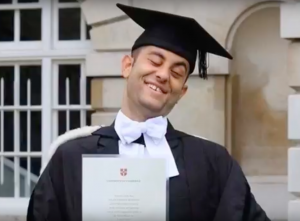

Allan Hennessy, a blind Iraqi refugee and a recent law graduate from the University of Cambridge, told the BBC in July 2017 that he might have joined ISIS or been killed in war if he was not able to stay in the U.K. as a refugee. In the end, the biggest hurdle refugees with disabilities face might not be any physical limitation but the social discrimination that impedes them from pursuing a better life. “When you’re an overweight, brown, blind guy climbing the greasy pole, everyone can see and they judge you – even though they are doing it too.” Hennesy explained to BBC reporters.

Whether individuals have a physical or mental disability does not necessarily limit their work and life prospects; however, there is a contempt for disabled refugees, according to Hennessy. Refugees with disabilities suffer from social discrimination, including being sidelined in many aspects of humanitarian aid, such as health and rehabilitation services, reports the Division of Social Policy and Development Disability.

A research report published by Research and Consultancy Unit (RCU) at Refugee Support and Metropolitan Support Trust defines disabled refugees in the U.K. as a “hidden population.” The number of disabled refugees and the multiple disadvantages they are up against are rarely known by local humanitarian service agencies and government authorities, the report notes. The research adds that most disabled refugees, in line with the rest of refugee cohorts, experience war and torture in their home countries and cultural and linguistic differences in their host countries. Their disabilities cast a further shadow on their livelihoods. As Hennessy wrote in The Guardian, “I have a disability; but I am not disabled.” It is the responsibility of both the U.K government and local communities to maximize the social capacity of refugees with disabilities by endeavouring to remove social stigmatization and ongoing impediments to aid.

Jason Hung is a visiting research scholar at UCLA for his original research project, “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: The Existence or Absence of Cultural Tolerance toward American Muslims?” He will be presenting his research at the 7th International Conference on Interdisciplinary Social Science Studies at the University of Oxford. He is also a featured writer for both the Oxford Human Rights Hub and the LSE Human Rights Blog. His research interests include migration issues, refugee rights, feminism affairs, women’s rights, and public health policies.