By Luiz Henrique Reggi Pecora, an M.A. student in human rights

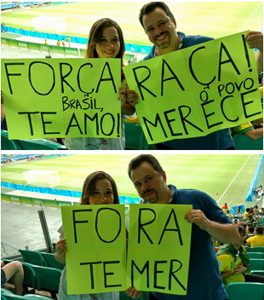

Primeiramente, fora Temer.

Firstly, down with Temer.

For Brazilians who do not recognize the legitimacy of Michel Temer’s government, this small phrase has gained the weight of a motto. Michel Temer has assumed office since May, when the Brazilian Congress approved the impeachment process of former president Dilma Rousseff, implementing a governmental project bent towards the interests of conservative groups. More progressive sectors of society have reacted energetically, not only opposing his governmental project, but also criticizing the questionable conditions that led to the removal of Mrs. Rousseff from office – for many, the impeachment is no more than an excuse for a coup.

After long years of prosperity, how did Brazil come to this critical scenario? The deepening of the economic crisis, combined with the “Lava-Jato” Operation (a series of investigations conducted by the Brazilian Federal Police over a huge corruption scheme involving large Brazilian companies and high-level politicians), contributed to an increasingly pessimistic and rebellious spirit within Brazil. At the same time, opponents of Mrs. Rousseff, many of whom were investigated themselves by “Lava-Jato”, supported campaigns to remove her from office, arguing that she committed a crime of “fiscal irresponsibility” when adopting certain macroeconomic policies.

The subject is controversial. The same manoeuvres had been applied by previous presidents for several years, albeit involving smaller amounts. The crime itself has a broad definition, with strong disagreement between specialists regarding whether it qualifies as a crime at all, or if it is a crime severe enough to justify the Impeachment of a legitimately elected president.

Brazil’s recent implementation of a conservative agenda raises concerns over the future of policies related to human rights, which are likely to suffer significantly in the coming years. Several federal programs involving socio-economic rights have seen their budgets radically reduced, if not completely eradicated, based on the argument of cutting expenses and reorganizing public administration to reach fiscal balance. As of this week, a constitutional reform that freezes the budget for the health and educational systems for twenty years has just been approved, risking damage to the already weakened Brazilian public schools and Unified Health System. The national literacy program has already had its activities shut down, and federal universities (where half of the vacancies are reserved for the affirmative action program) will see a drop in investments by almost 50%. “Bolsa-família”, the world renowned redistributive program that provides minimum subsistence support for millions, will also suffer a change in registration requirements, obstructing access for the most vulnerable families.

More ominously, human rights policies as a whole, risk suffering a substantive depletion. Since Mr. Temer’s election, the Secretariat for Human Rights has been downgraded from Ministerial status to a subsection of the Ministry of Justice, losing its autonomous budget and answering to a new Minister who is oriented towards very contentious public safety policies.

This systematic targeting of human rights policies has transpired in just the first four months of Mr. Temer holding office. The argument of fiscal balance, often used to justify the need for the measures taken against human rights oriented programs, reveals itself inconsistent as Mr. Temer has granted considerable concessions for public spending in other areas: generous salary readjustment of public servants, debt relief for federal states, and even extra expenditure for the Olympics. It is more likely that the change in policies directed for the fulfilling of socio-economic rights are an attempt to gain the approval of conservative sectors of society, who have been gaining more political influence in the past few years. Indeed, the Brazilian Congress currently has the largest amount of conservative members since the military coup in 1964.

If Mrs. Rousseff’s government was already criticized for not prioritizing human rights issues, the new agenda enforced by Mr. Temer completely neglects the state’s obligations towards rights that are not only entrenched in the human rights covenants ratified by Brazil, but also within the Brazilian Constitution itself. While his speeches advertise a conciliatory program for the country, his actual policies point to a consistent retrogression. If Mr. Temer continues with this trend, human rights in Brazil will be once more left behind as a disposable facet of the state’s concerns.

Luiz Henrique Reggi Pecora is a graduate student at the Human Rights Studies M.A.’s program at the Institute for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University. His research interests include indigenous rights, political activism in civil society, and migrant’s rights.

This article is brilliant and reflect exaclty what is currently going on in Brazil.

Bruno Pegorari and my opinion are same. this article was really brilliant which is represented that situation what was running in Brazil.