The first History in Action Project Awards (HAPA) were announced in September. Here, we catch up with the three inaugural winners to find out more about their projects, beginning with fifth-year doctoral candidate Nick Juravich.

Nick Juravich is a doctoral student in US History who studies education, social movements, labor organizing, and metropolitan development in the twentieth century. His dissertation examines the creation and development of paraprofessional programs, which brought thousands of working-class mothers into public schools to improve pedagogy, build links between schools and communities, and create careers in education in the 1960s and 1970s. Nick with be working with the South El Monte Arts Posse (SEMAP) as part of their ongoing community-based history and archiving project “East of East: Mapping Community Narratives in South El Monte and El Monte.”

Q: How will you be using your HAPA grant?

A: I’m traveling to South El Monte, California from January 5-16 to work with SEMAP for two intensive weeks. I’ll be working with two fellow Columbia PhD candidates: Daniel Morales (also a HAPA winner), and Romeo Guzmán, who co-directs SEMAP and East of East. We will be conducting oral histories and digitizing personal collections of documents and photographs. The City of South El Monte has offered us access to their own archives, which we’ll also be digitizing. We’ll also be visiting South El Monte High School with SEMAP and KCET (the largest independent broadcast network in the US) to present our work and conduct workshops on oral history. As a way of publicizing this project and thinking about research in “real time,” Daniel and I will also be blogging about our trip with Tropics of Meta.

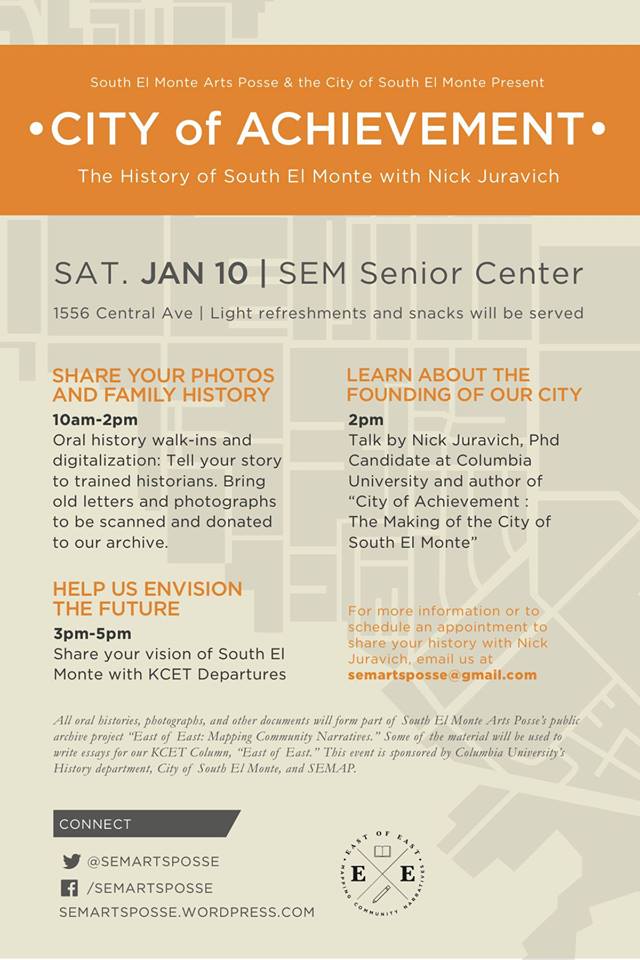

The biggest day of my visit will be Saturday, January 10, when we’re hosting “City of Achievement,” a full-day series of events at the the South El Monte Senior Center (flier above). From 10am-2pm, we’ll be doing oral histories and personal archive digitizations on a “walk-in” basis with a team of graduate students from UCLA and Columbia. At 2pm, I’m giving a presentation and leading a discussion on the founding and history of South El Monte. From 3-5pm, KCET will interview residents about their visions for the present and future of South El Monte.

One of the most exciting parts of this project is how the research, archive building, and community outreach are intertwined. The materials we collect will be digitized with East of East for other students, scholars, writers, artists, and community members to use long after we’re gone. Local high school students will be shadowing us while we conduct oral histories on January 10th, and their own experiences and ideas about their city will inform the questions we ask and the way we think about these histories. They’ll also be learning to continue this work and push it in new directions in years to come. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Q: What organizations are supporting or sponsoring this project?

The South El Monte Arts Posse is the primary sponsor. Their co-directors, Romeo Guzmán and Carribean Fragoza (a writer, artist, and associate producer at KCET) have built an amazing project that combines social arts practice, archive building, and public history. They’ve documented this work through a partnership with KCET Departures, where they coordinate content from South El Monte and El Monte. The project thus far has included public art installations, digitization of city records and personal collections, oral histories, creative writing workshops, and cultural events. SEMAP’s inaugural East of East program, in January and February of 2014, was funded by the Los Angeles City Department of Cultural Affairs and the National Performance Network. They’ve also created a Reader on the history of South El Monte and El Monte, which features contributions from ten members of the Columbia graduate community and is published online and updated regularly by KCET.

For my visit, SEMAP has done a huge amount of legwork to connect me to oral history narrators, high school teachers, City officials, and other graduate students. I’m hoping to pay them back for this with new materials for their archive, some new writing for their KCET page, and some fun events to keep momentum going in South El Monte and El Monte around this project.

SEMAP has three long-term partners that deserve mention. The first is the City of South El Monte, which supported the project and has provided access to their own, largely uncataloged, city records and archives. The second is La Casa de El Hijo del Ahuizote in Mexico City, which has helped to build the digital archive and will be storing the materials we collect during our two weeks. The third is KCET, where many of these stories and materials will be shared with a wide audience.

In addition to these sponsors, we’ve gotten great support from friends in NYC and LA. The HAPA grant is a huge boost – I wouldn’t be able to make the trip without it – and the Lehman Center for American History at Columbia has chipped in printing costs for materials for our events. The Columbia Center for Oral History Research (CCOHR) is loaning some oral history gear for us to use, and in In Los Angeles, the UCLA Center for Oral History Research – whose director, Dr. Virginia Espino, attended the CCOHR Summer Institute with me in June – is also loaning oral history gear. Fellow graduate students from UCLA and UCSB are joining us to collect oral histories. Tropics of Meta, a history blog run by Alex Cummings (a graduate of the Columbia PhD program and professor at Georgia State) and Ryan Reft (a recent graduate of UCSD’s doctoral program in history with an MA from Columbia) is providing a platform for live blogging and reflection. Overall, I think it really shows the capacity of “history in action” to bring people together from all sorts of different places.

Q: What opportunities for “community outreach” (as it is described in the HAPA grant) do you envision?

Our two big opportunities for outreach in South El Monte are our visit to the high school and our event day on January 10th. I’m really looking forward to these conversations with the people who lived this history and live with its present legacy and future legacies and possibilities. I’ve already written one piece for SEMAP on the founding of South El Monte, and the local response to it has helped me find oral history narrators and new topics to focus on during this round of research. That give-and-take helps us shape better projects, and also hopefully creates opportunities for new ones.

Contributing new materials to the archive is also a form of community outreach, at least the way SEMAP does it, because these materials will be accessible to the community. In that way, the archive helps to sustain community outreach long after the two moments I’ve described above have passed.

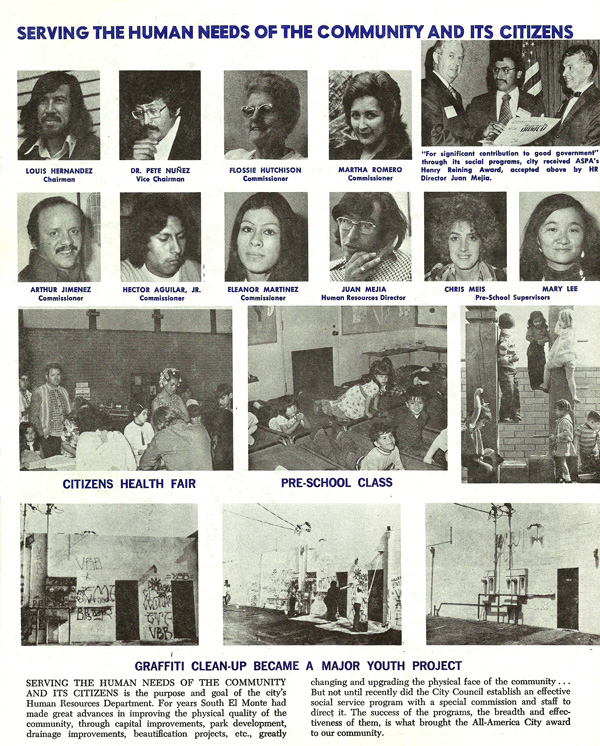

From the South El Monte Newsletter ca. 1975 | Image: Courtesy of the City of South El Monte and SEMAP

Q: How does this work connect to your research at Columbia?

My dissertation is an in-depth look at paraprofessional educators: working-class women, primarily the mothers of schoolchildren, who went to work in local schools amid the freedom struggles and War on Poverty of the mid-1960s. In South El Monte, community educators in many different roles worked to improve pedagogy and curriculum (including bilingual, early-childhood, and special education), supported students and parents as they negotiated official educational settings and challenged institutional racism and classism, and worked to make schools more responsive to community needs. Some of my interviews and archival research on this trip will focus directly on these topics, and help me understand how these programs took shape in South El Monte.

South El Monte’s history as a working-class suburban city in Greater Los Angeles offers a very different angle on these questions than the big-city studies that I’ve worked on. The city was founded by residents who were told their unincorporated neighborhoods were “only fit for chickens,” in 1958, but over the course of the 1960s and 1970s, they won several national prizes for civic participation. These victories were built on a broad base of everyday organizing, and educational activism, in particular, was central to South El Monte’s culture of participatory citizenship. Struggles over schools and opportunities for youth brought people of different generations, classes, races, and ideologies together, doing everything from anti-racist organizing to public health projects to community arts programs. This isn’t to say that racism, capitalism, punitive immigration regimes, and many other sources of inequality didn’t assail and ascribe the lives of working-class South El Monte residents. They did, but never completely, and the ways in which people organized to fight back and fight through these challenges – politically, socially, and culturally – are fascinating.

South El Monte has a lot to offer historians, and the history here has a lot of potential to inspire and inform the present, but at the moment, there really aren’t any major institutions (either in SEM or beyond it) that work on this history. SEMAP – in the tradition of community activism in South El Monte – has really stepped into that void in the last few years, and I’m excited to be a part of that.

Q: What drew you to this particular project, as you proposed it?

When Romeo first put out a call for articles to Columbia graduate students last year, I jumped at the chance to write on education and community activism in Southern California (my work mostly focuses on New York City). As I worked on the piece, it developed into a short history of the founding of South El Monte that focused on the role of community activism in creating and sustaining it.

Writing that piece raised all sorts of interesting questions for me in my own research, and it also drew responses from community members, many of whom expressed interest in sharing their own stories to help improve the work. Some were very frank: they told me I’d missed key things, that I needed to read more and listen more, but they also offered their own insights, and they’ve helped connect me to people and resources who will make this work stronger. Theses responses have drawn me further into the project, and I applied for the HAPA grant to build on what got started with the first piece.

Q: What drew you to the idea of “History in Action” more generally? What does “History in Action” mean for you?

The history I study – the recent past – is always active. Oral history is central to my research, and creating an oral history is a collaborative process that leaves me with a responsibility to my narrators. They’ve committed time and energy to remembering and sharing their stories, and they deserve to see them archived, presented, and cited in ways that reward their commitments and benefit their communities. That doesn’t mean treating what they say as gospel, but it does mean sharing both the archival materials (recordings and archives) and my own interpretations of them with the wider community (South El Monte, in this case). This might generate new collaborations, it might generate critiques, it might even generate conflict, but if this work isn’t responsible and responsive to the communities whose stories it builds on, then why should they share them with us?

More broadly, then, “History in Action” (or “public history”) offers the opportunity to improve our own research, writing, and teaching through collaborative work with the people whose history we study. This isn’t about carrying knowledge forth from the academy, but about building sustained exchanges that generate opportunities for everyone involved. SEMAP have been an inspiration as I’ve thought about my own research, because their project has been built from the ground up with commitments to democratic and creative historical practices. They’ve democratized access to their archive by making it public and digital. They’ve also democratized interactions between and among scholars, artists, writers, and community members by creating new spaces and new modes of sharing historical knowledge within them. They’re also thinking about the future: not just about doing this work right now, but about training folks – particularly students and youth – to keep doing it, and preserving the materials we’re using through the public archiving process so that they can be revisited, reused, and reinterpreted down the line. The result of all of this collaborative work is far richer than anything a single scholar writing a monograph on South El Monte could produce, and its impact in the community is far greater, too.

Q: Any final thoughts?

It’s gonna be a fun two weeks. And THANKS to all of the organizations, including the History in Action initiative, that are making this happen.